SCREEN

BUSINESS

How screen sector tax reliefs

power economic growth across

the UK 2017–2019

A report comissioned by BFI

from Olsberg

•

SPI with Nordicity

December 2021

Acknowledgements

Foreword

Summary

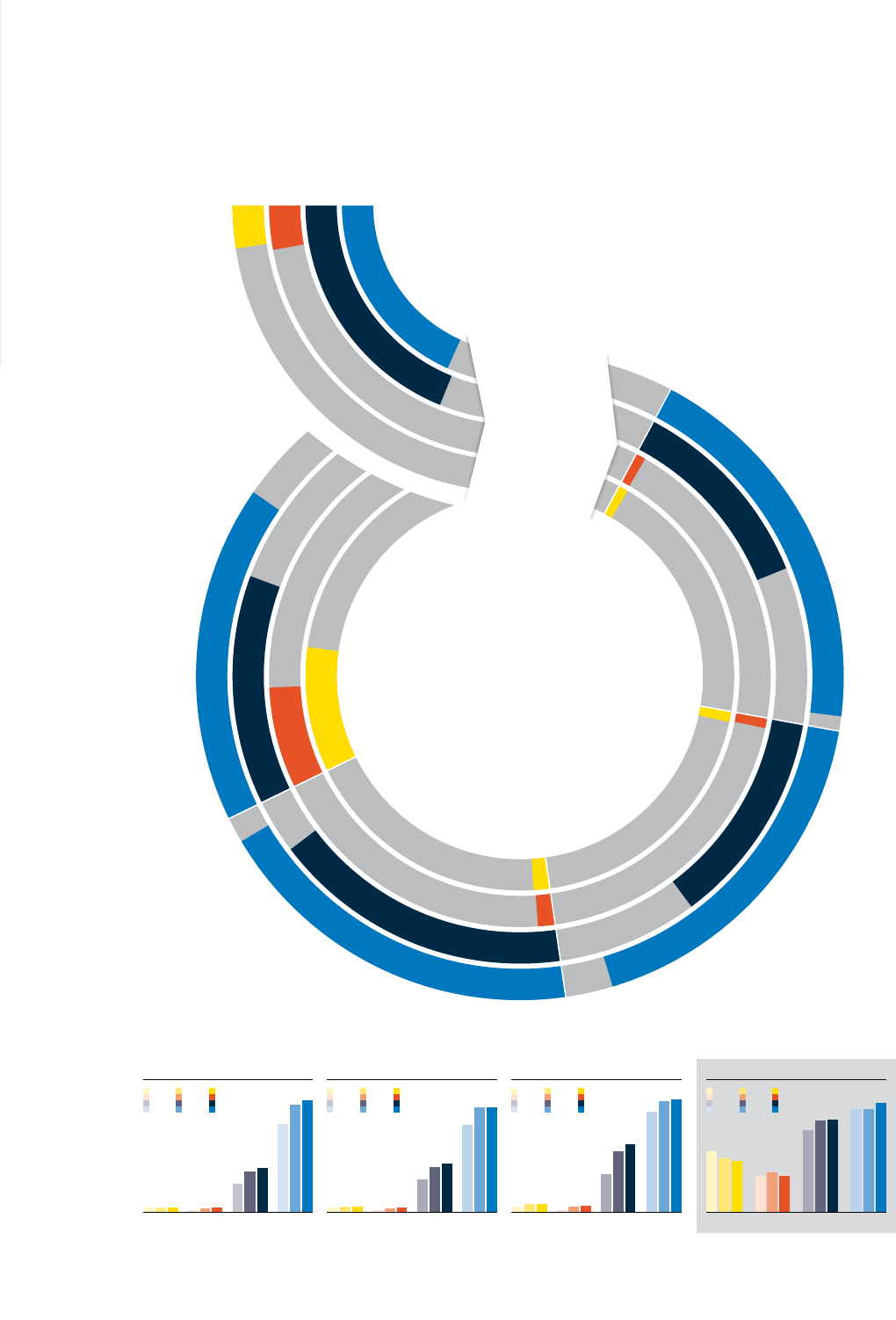

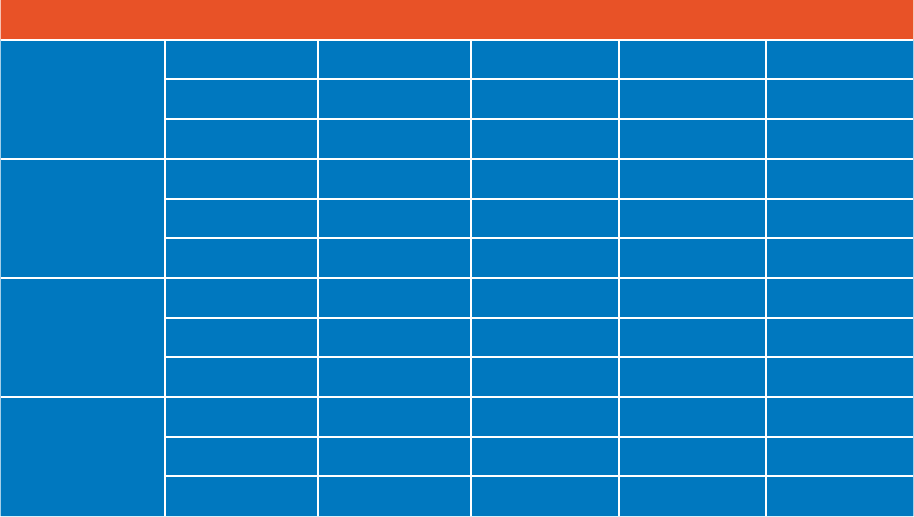

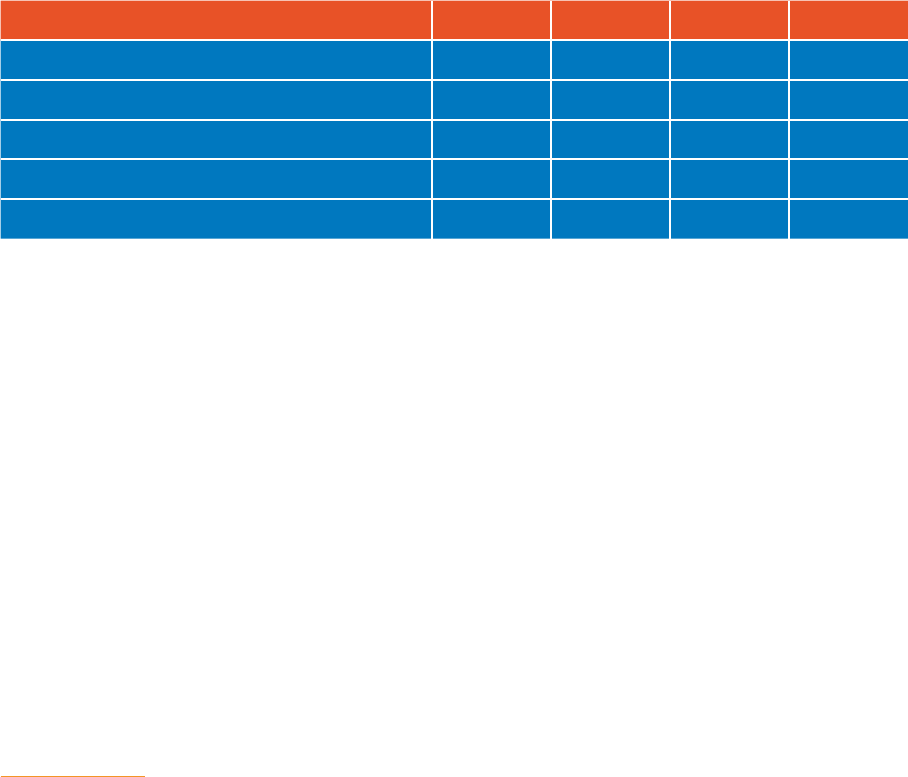

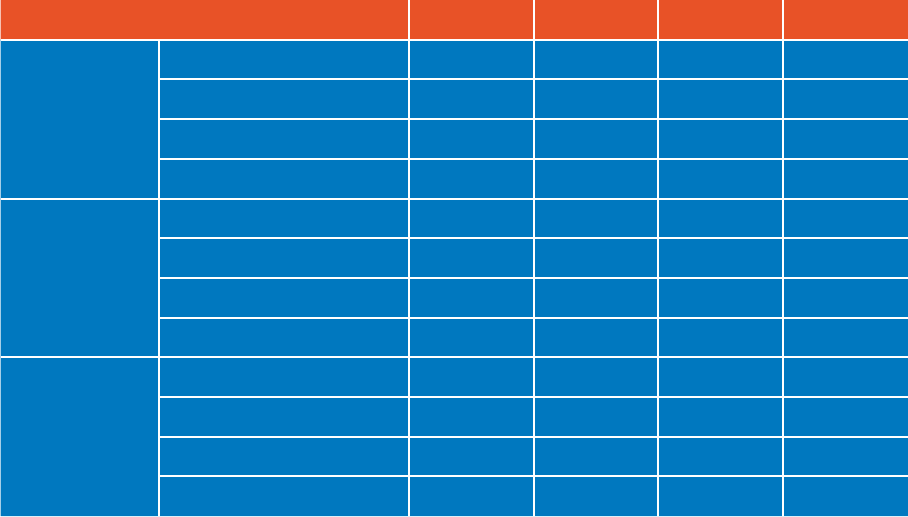

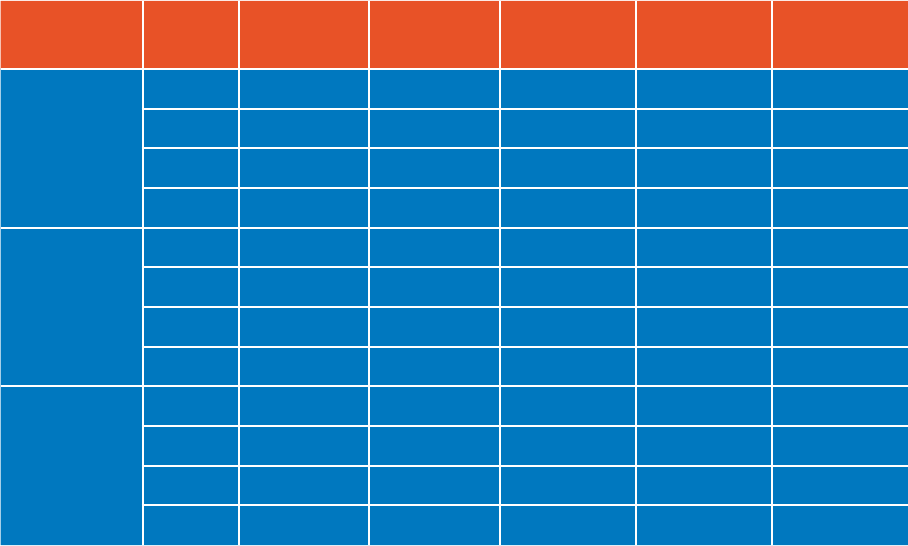

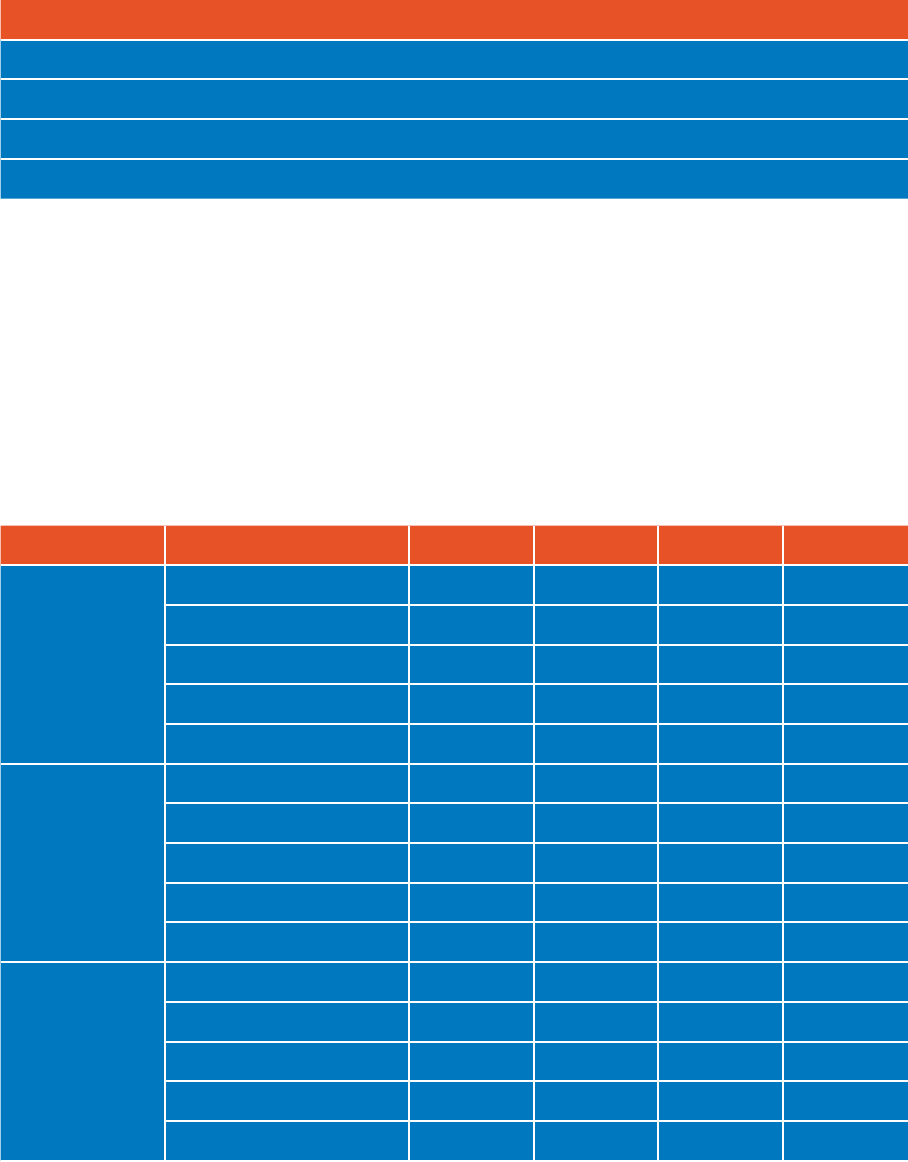

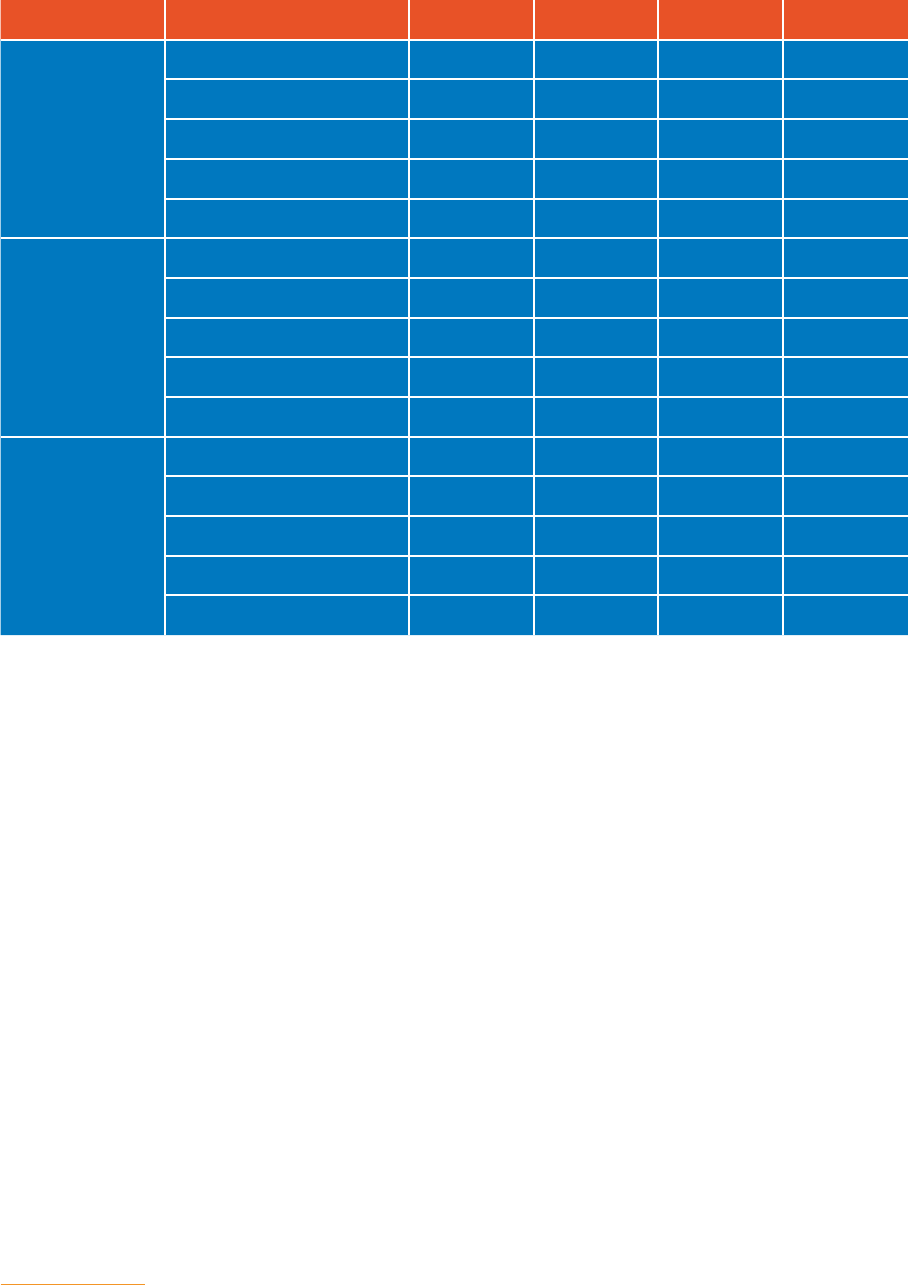

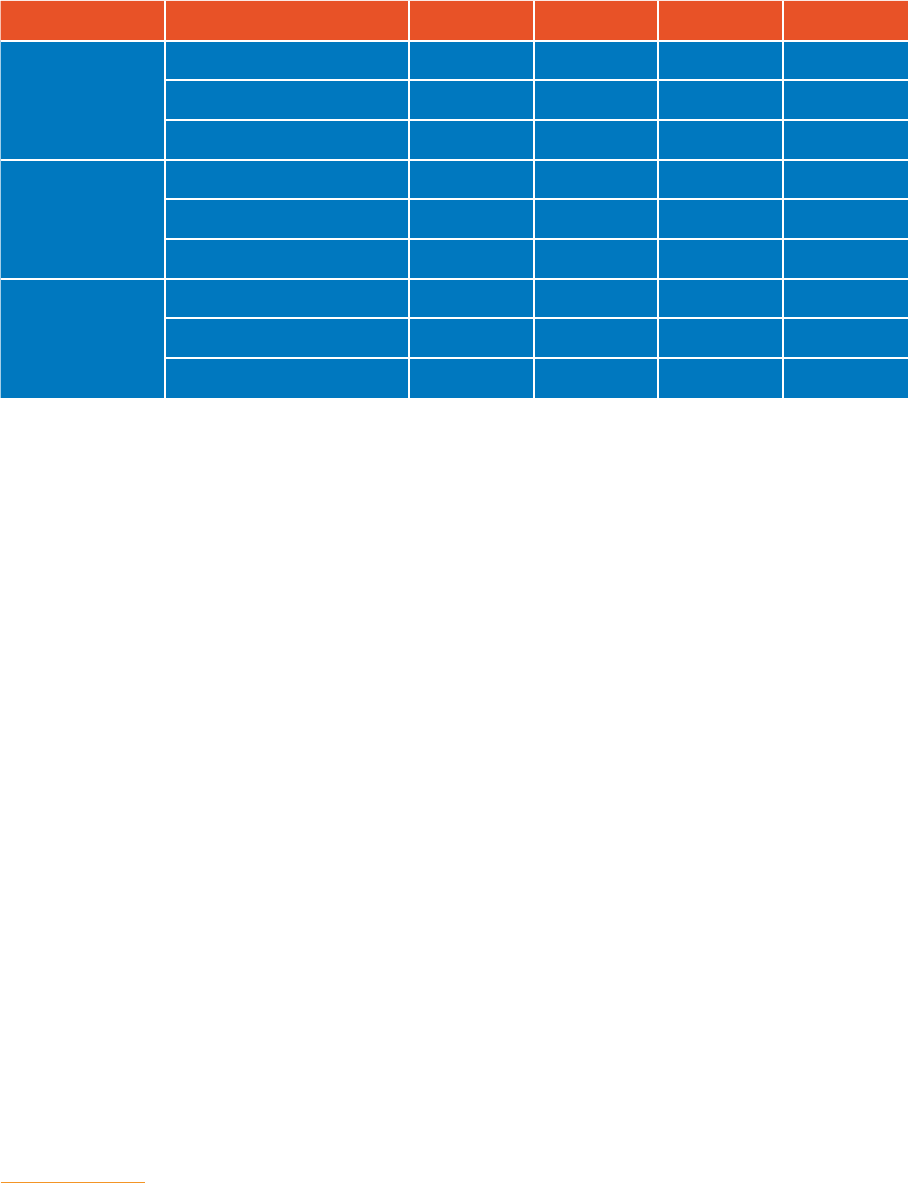

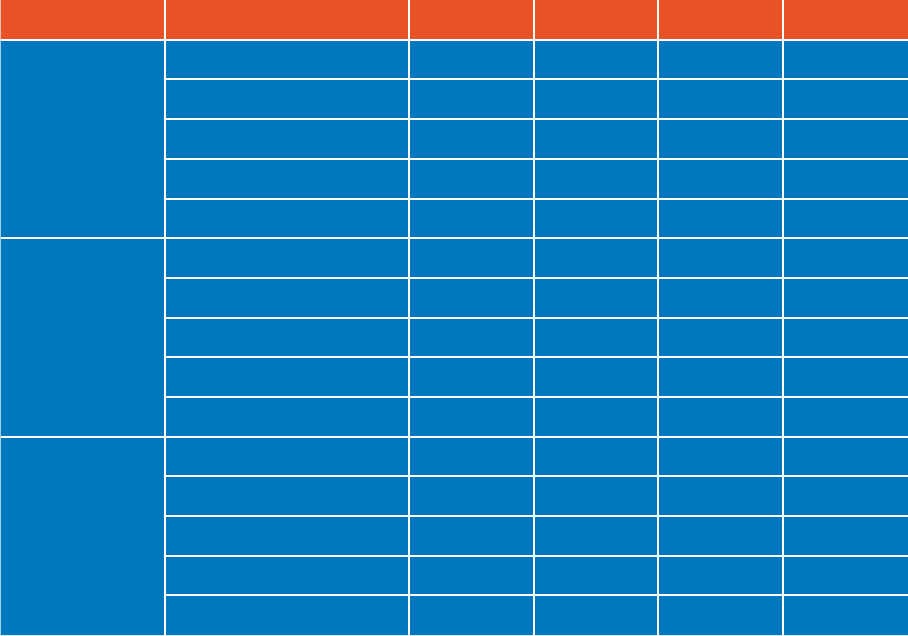

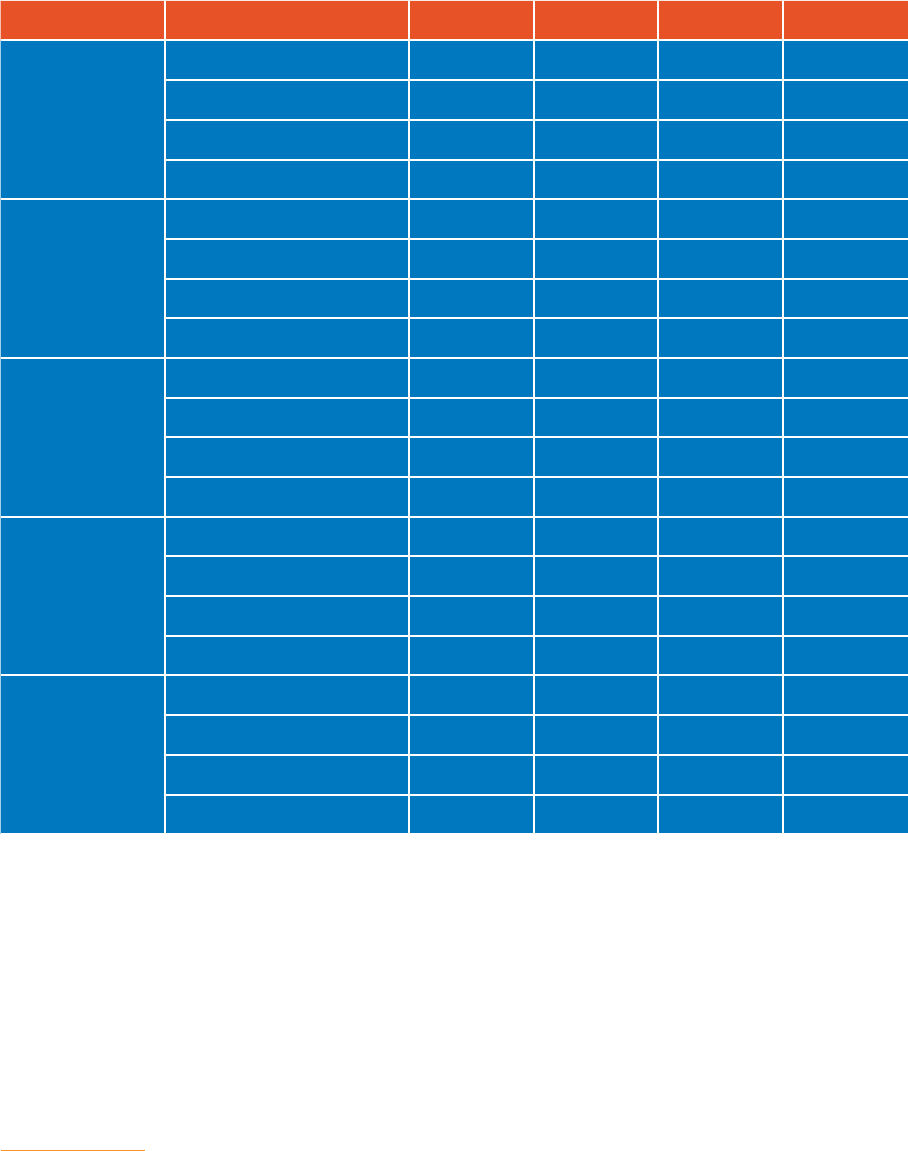

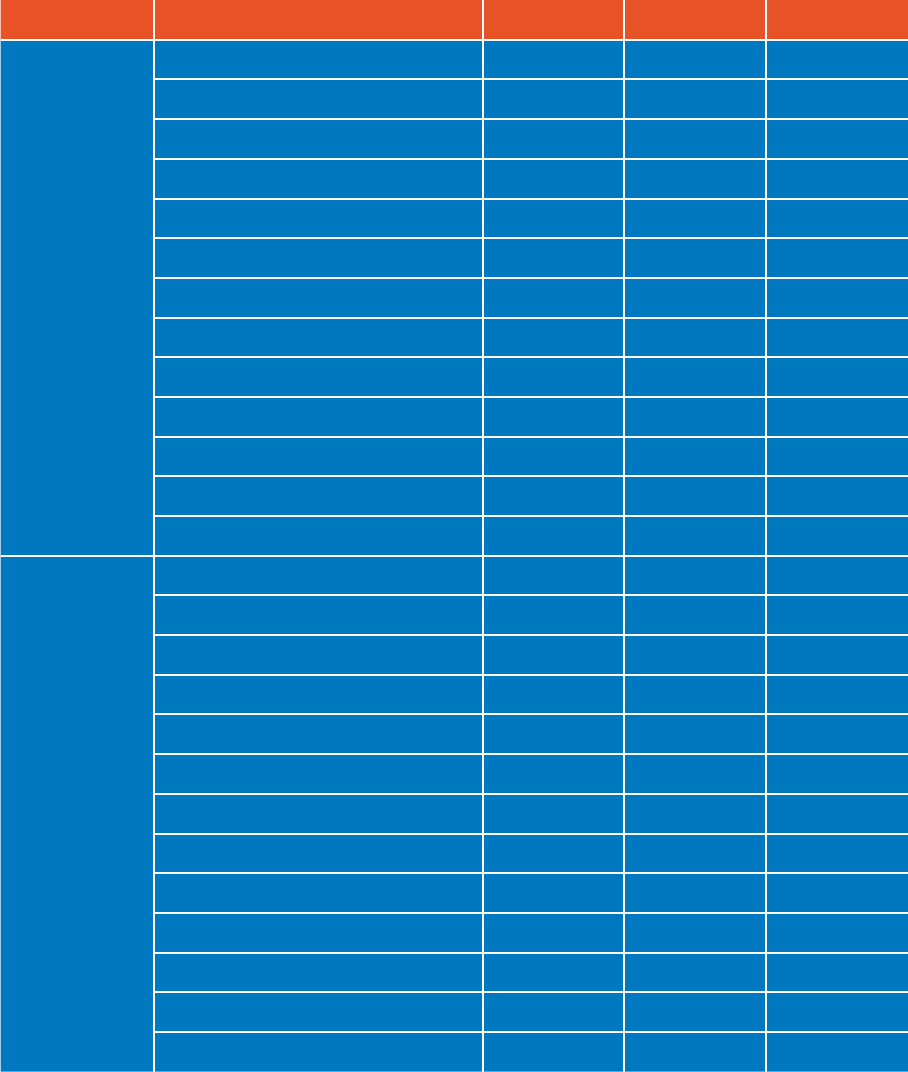

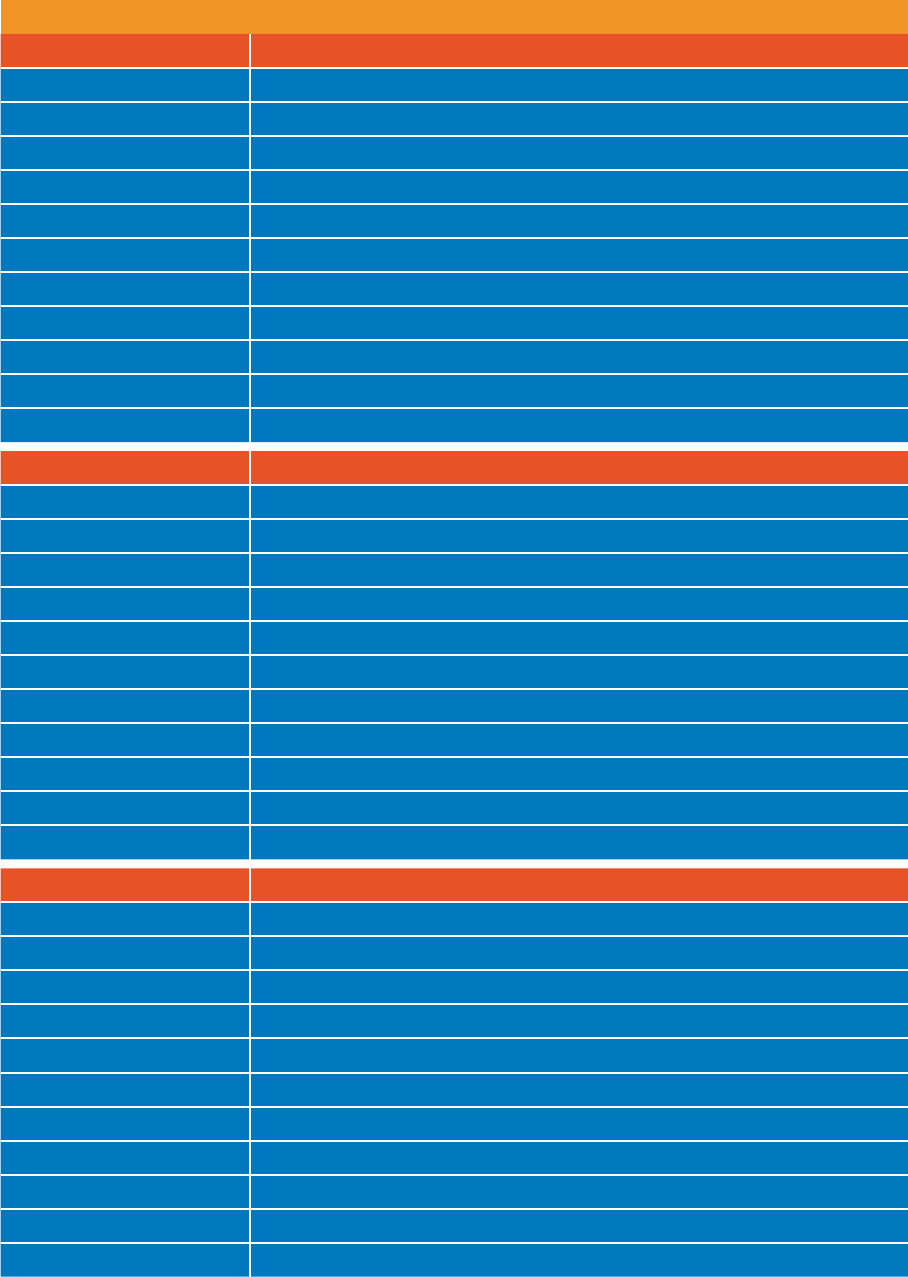

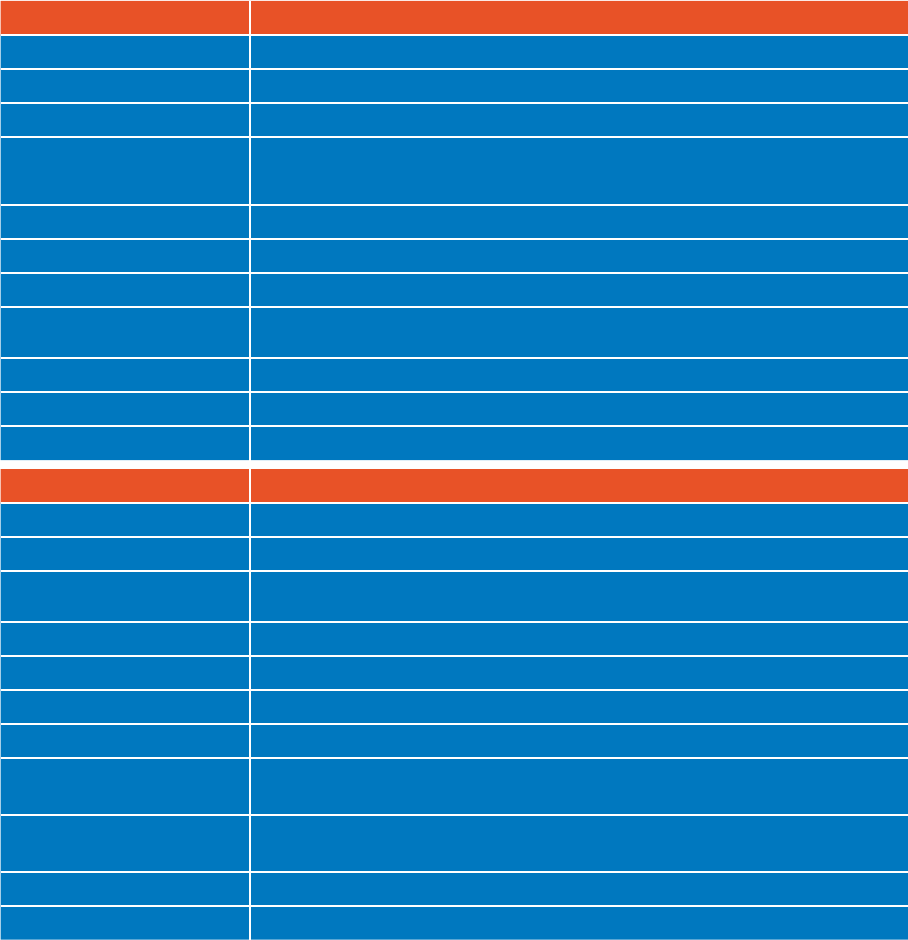

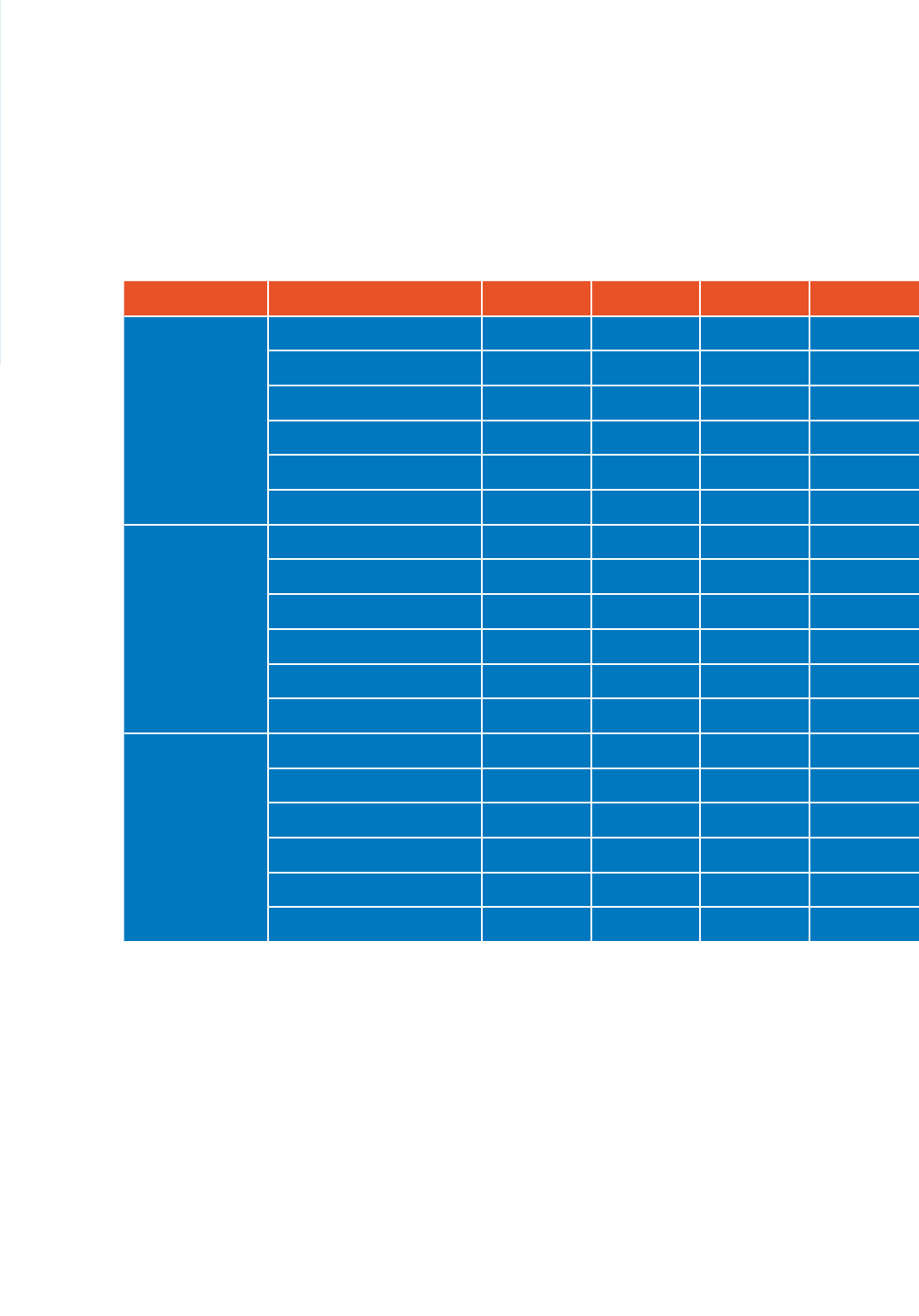

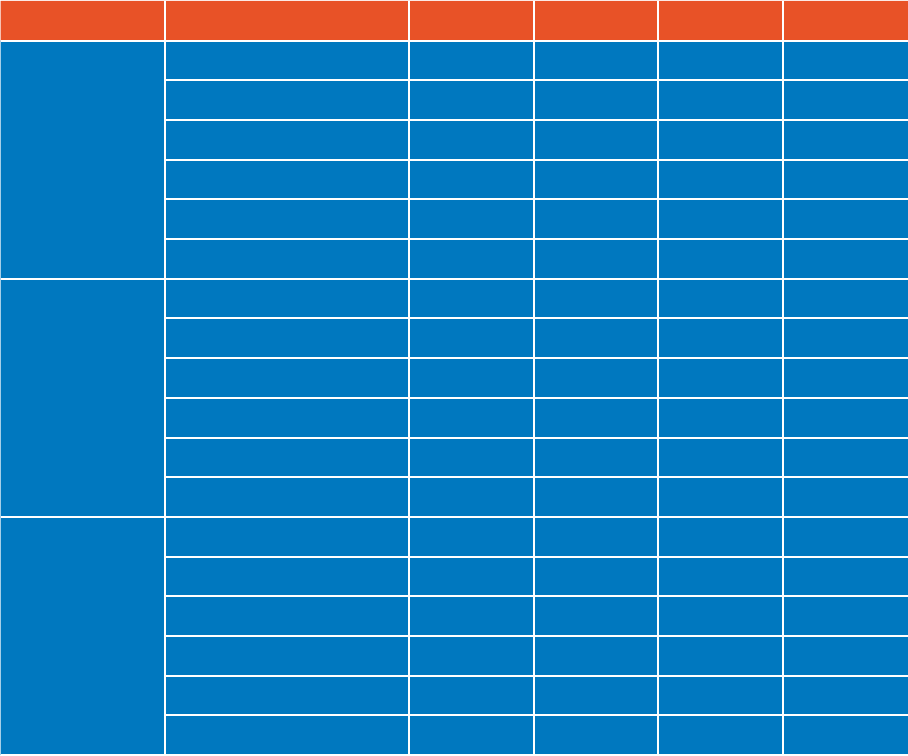

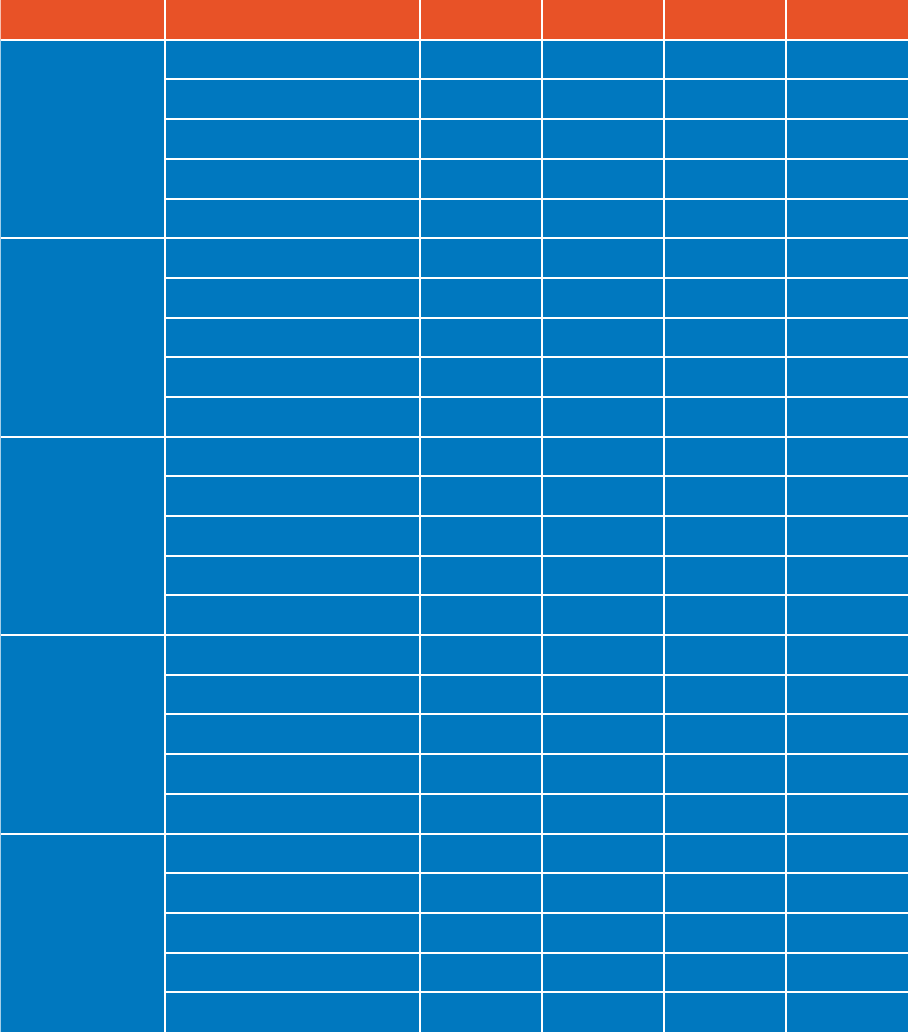

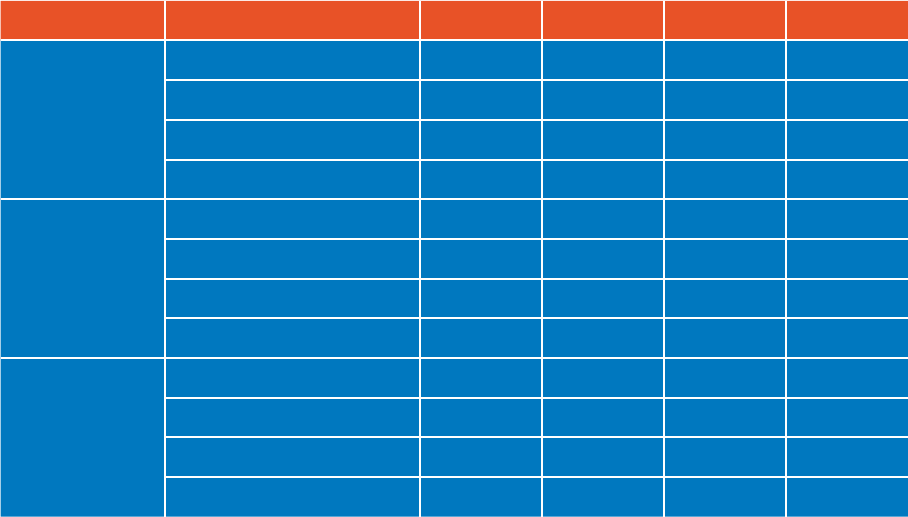

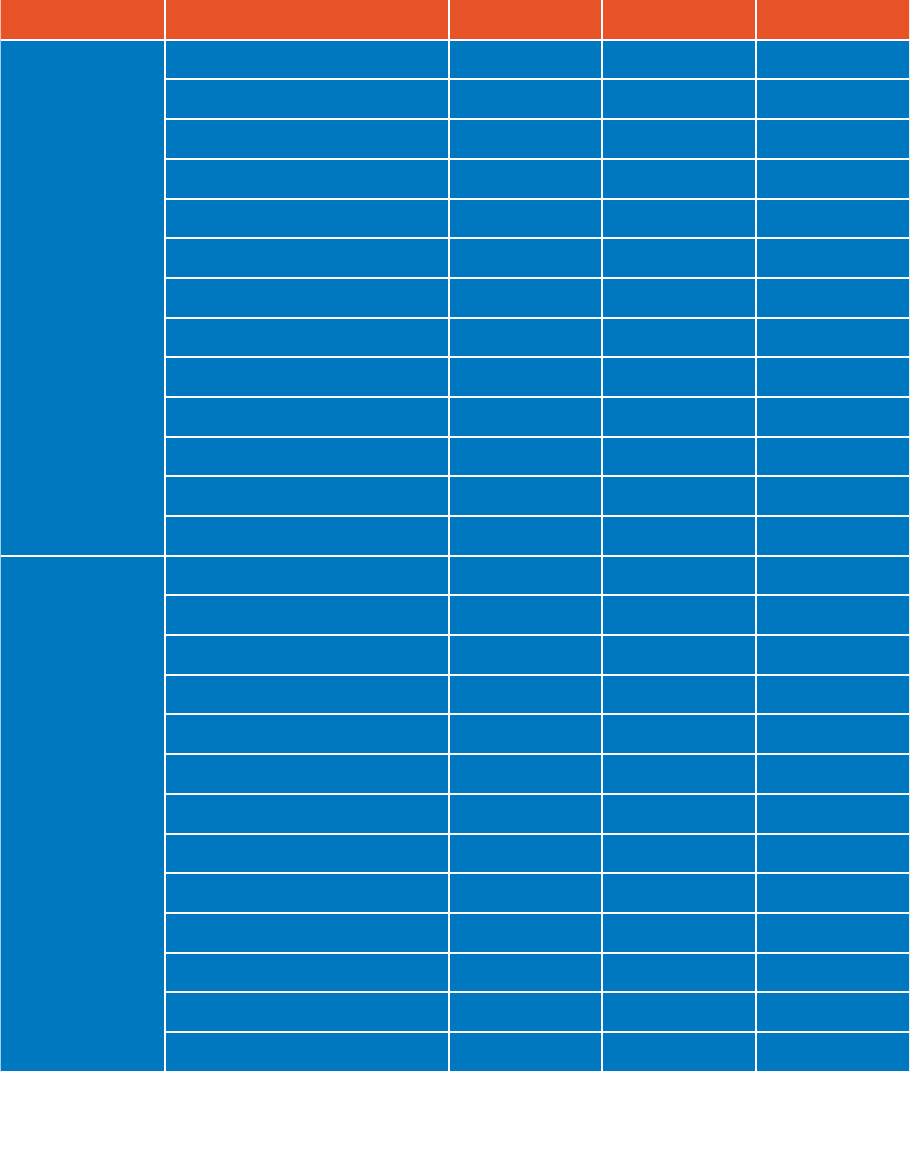

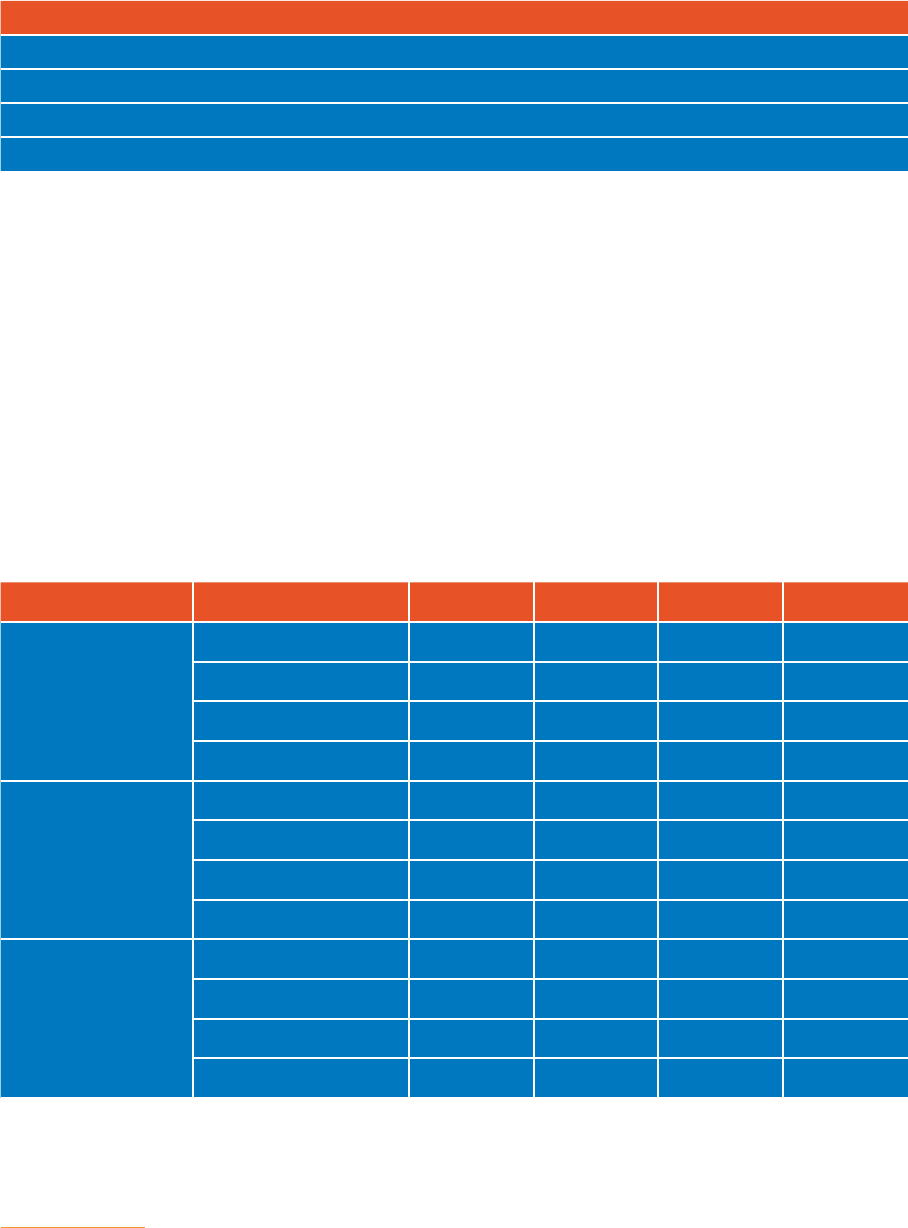

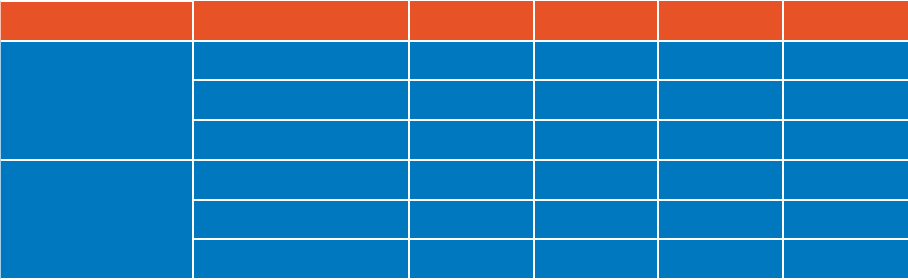

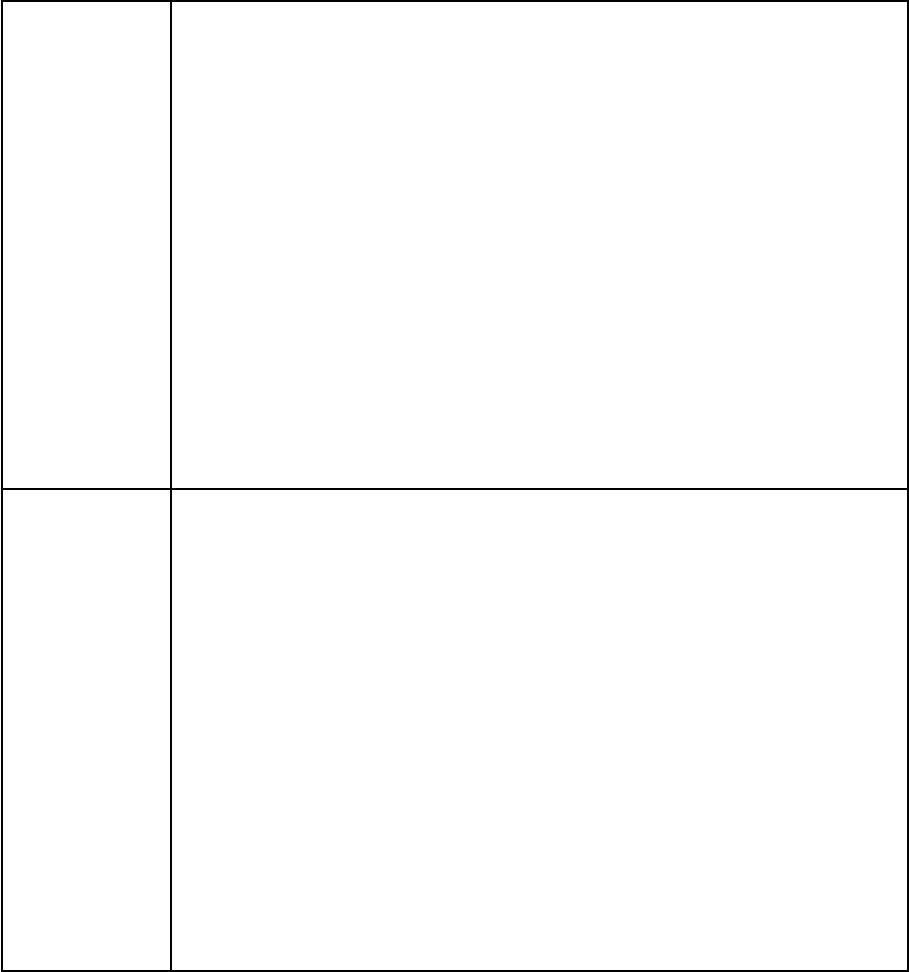

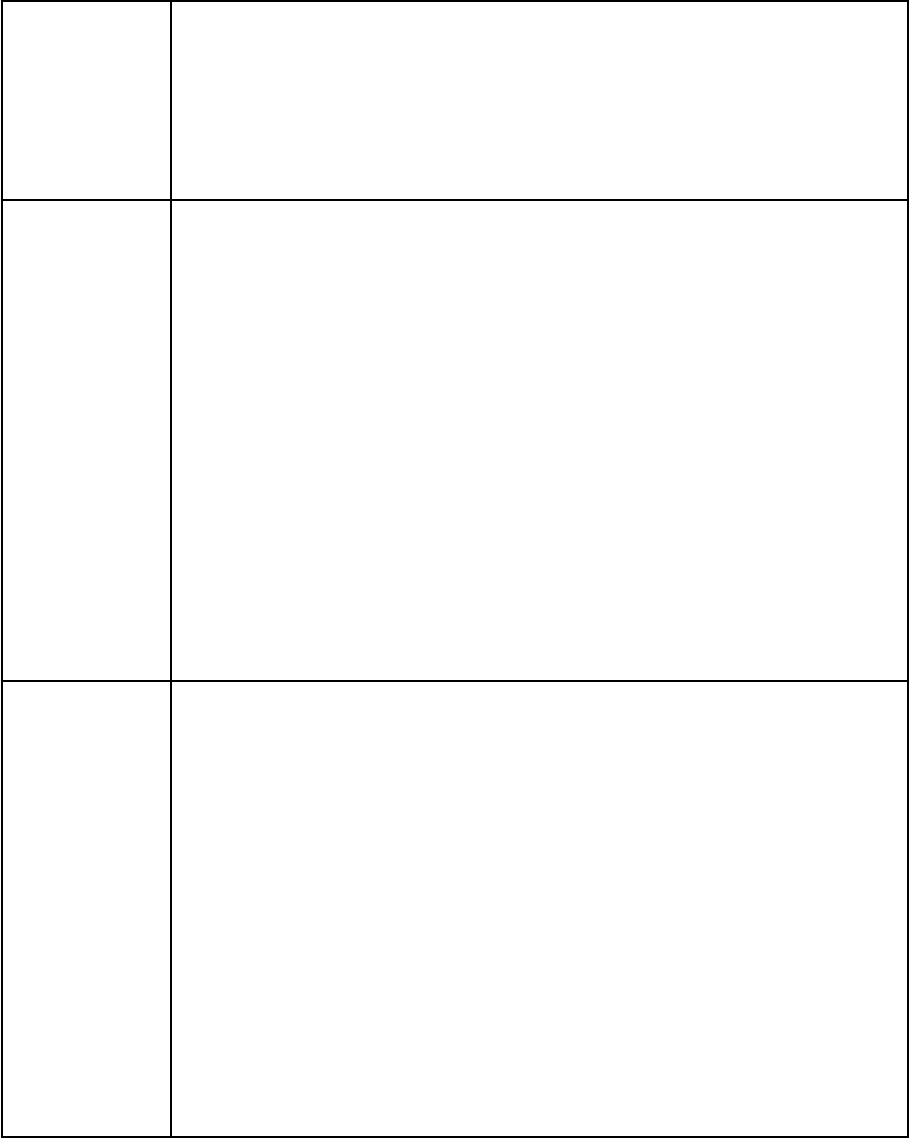

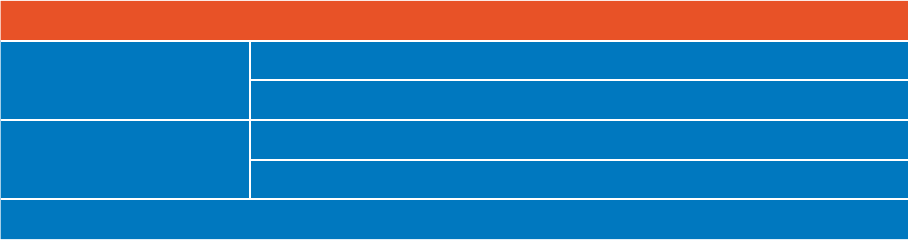

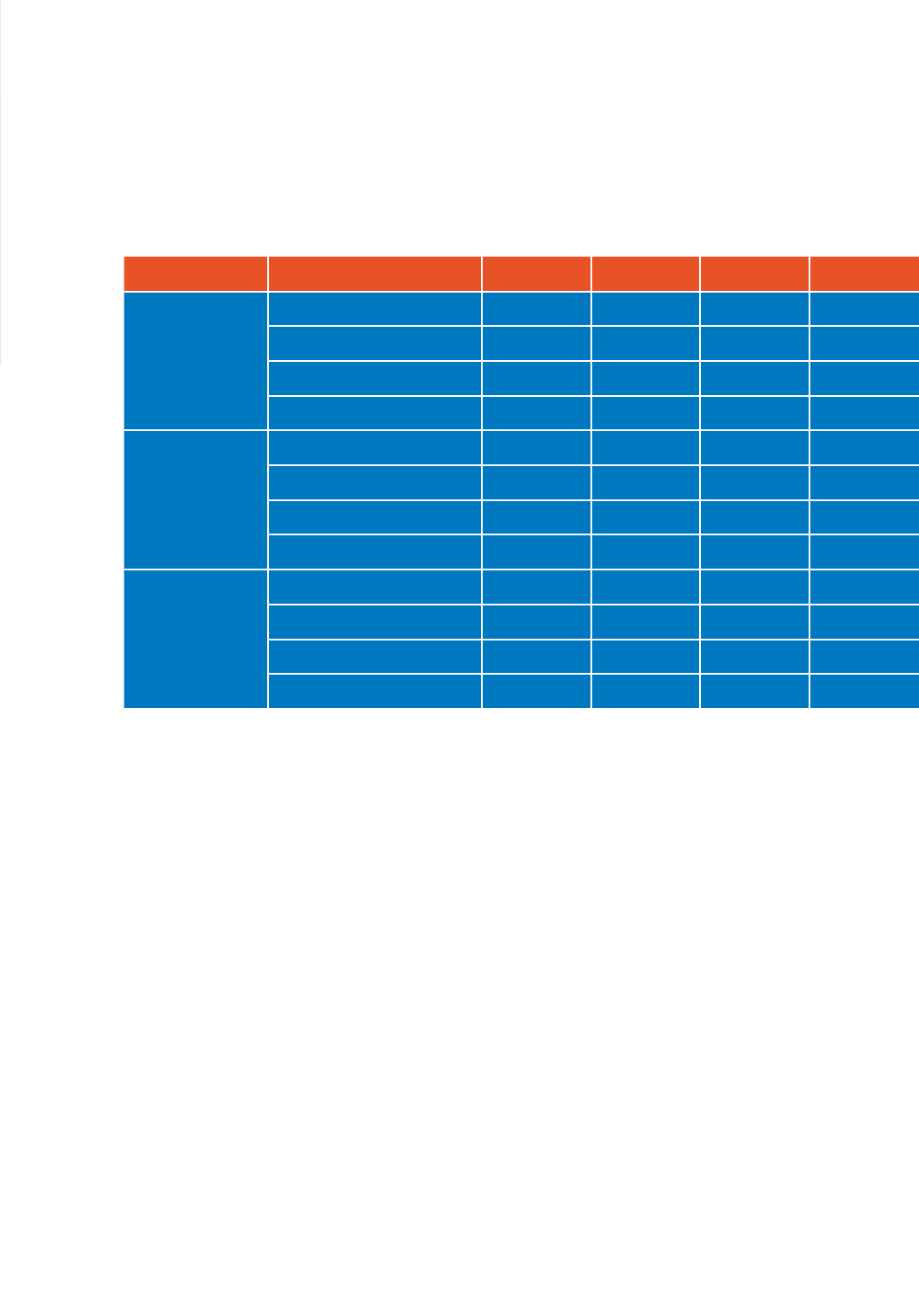

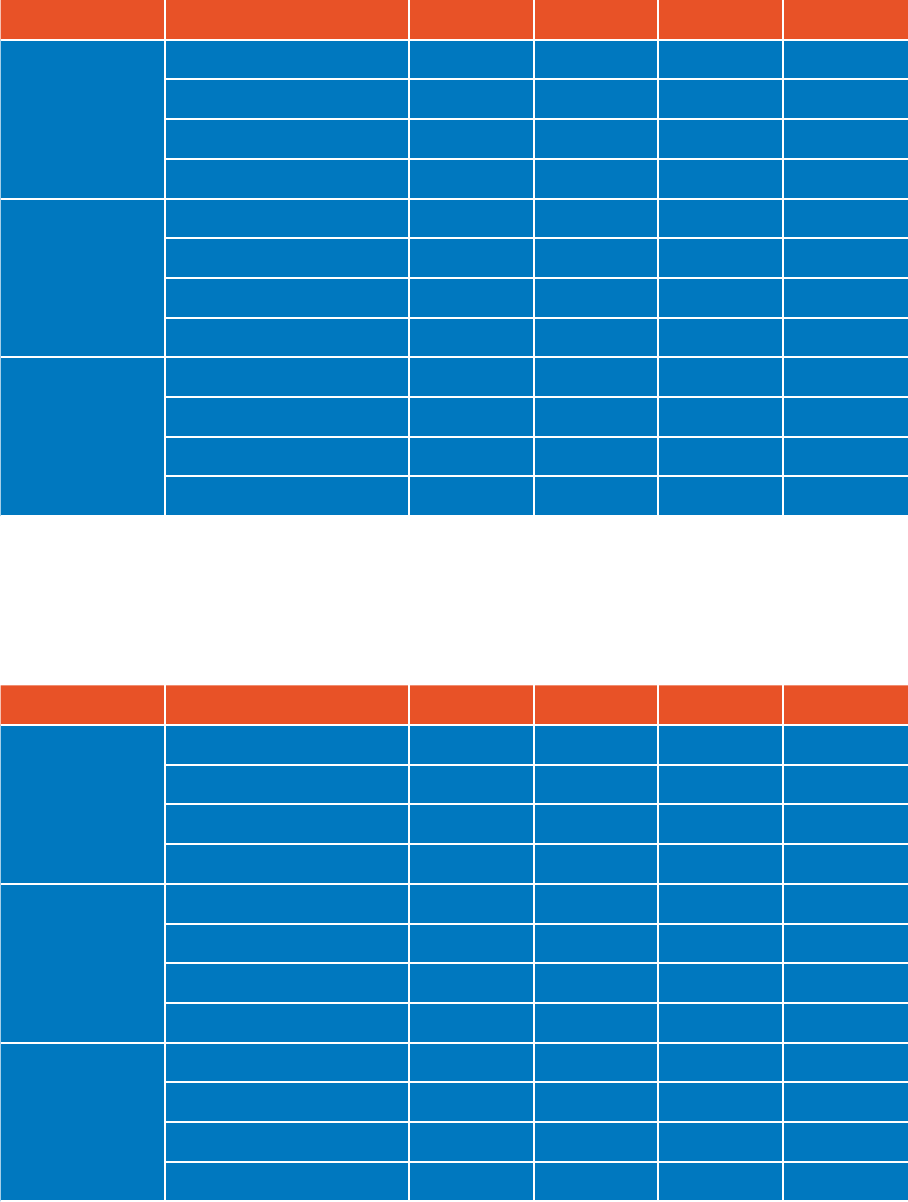

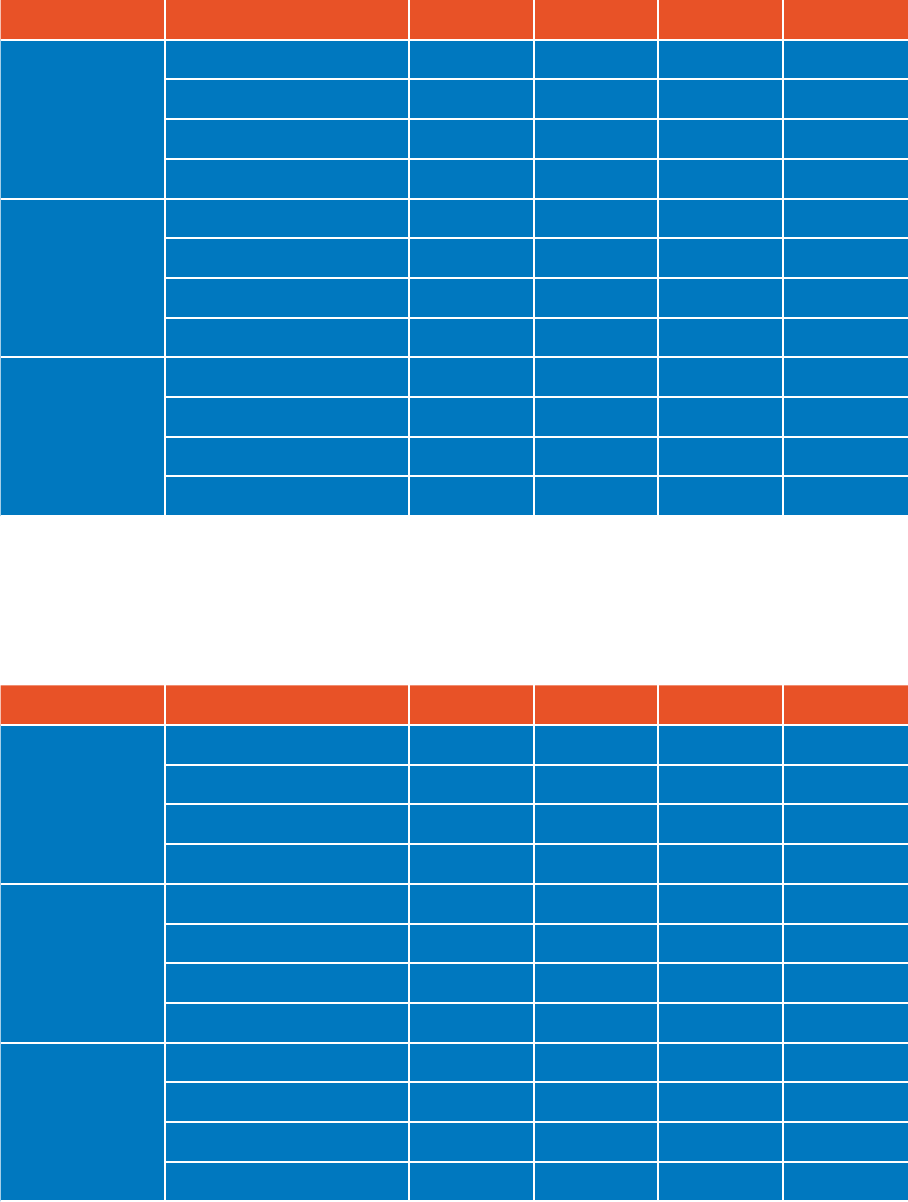

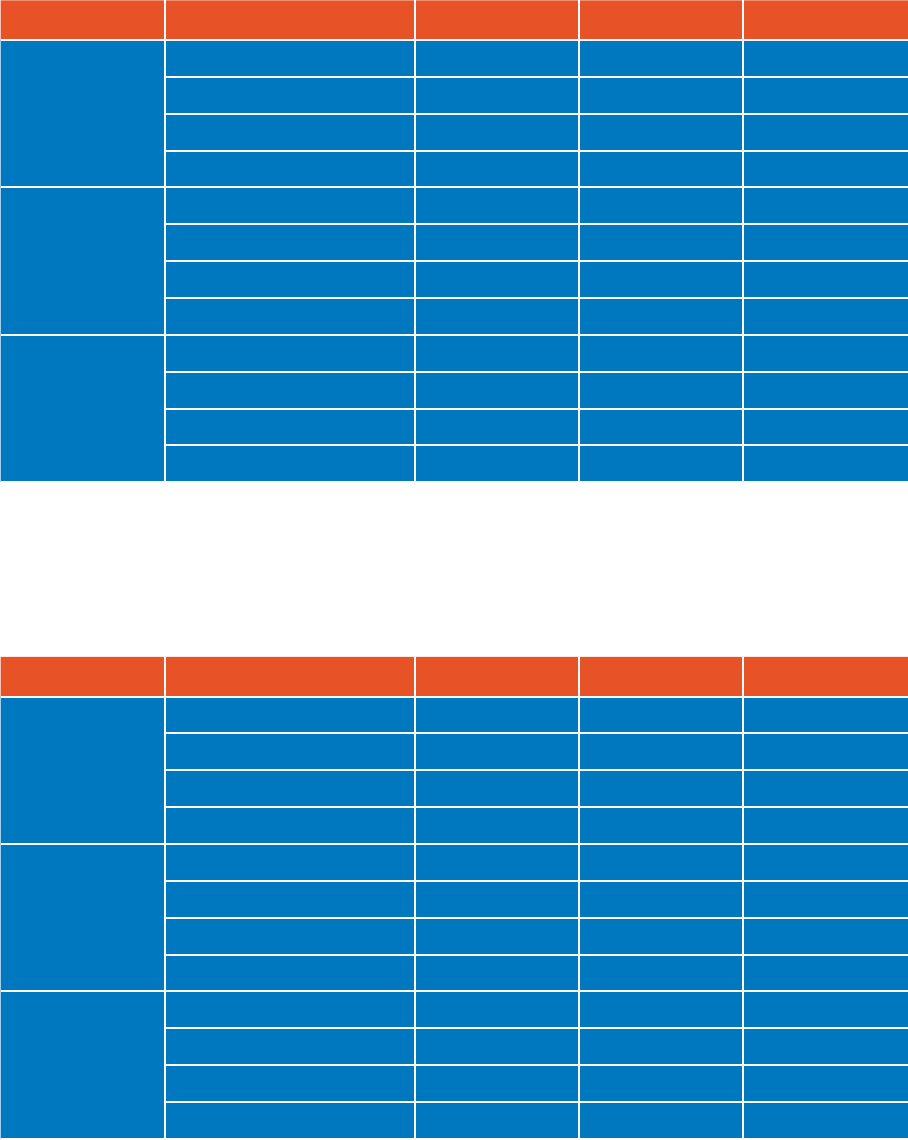

Tax relief-supported impact, 2019

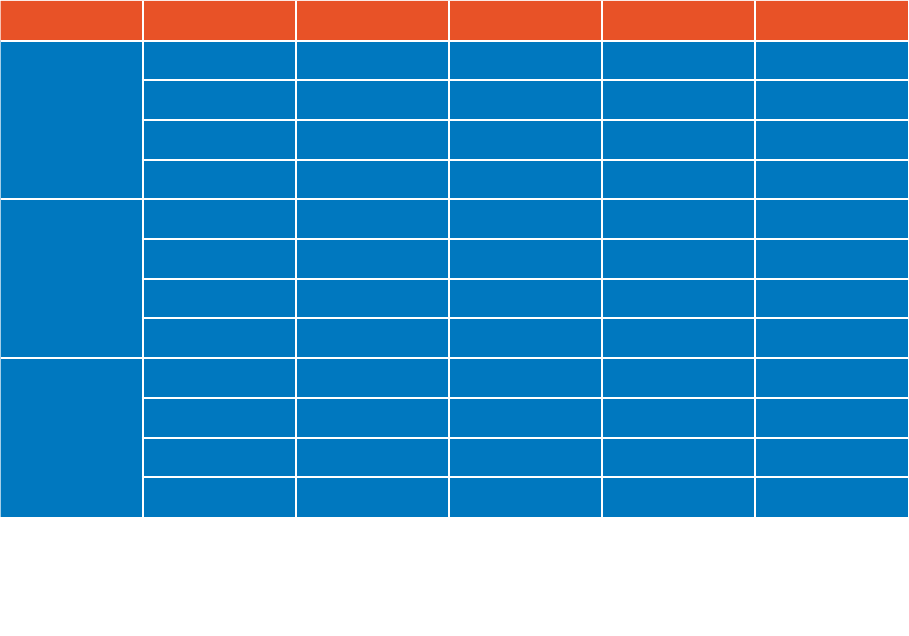

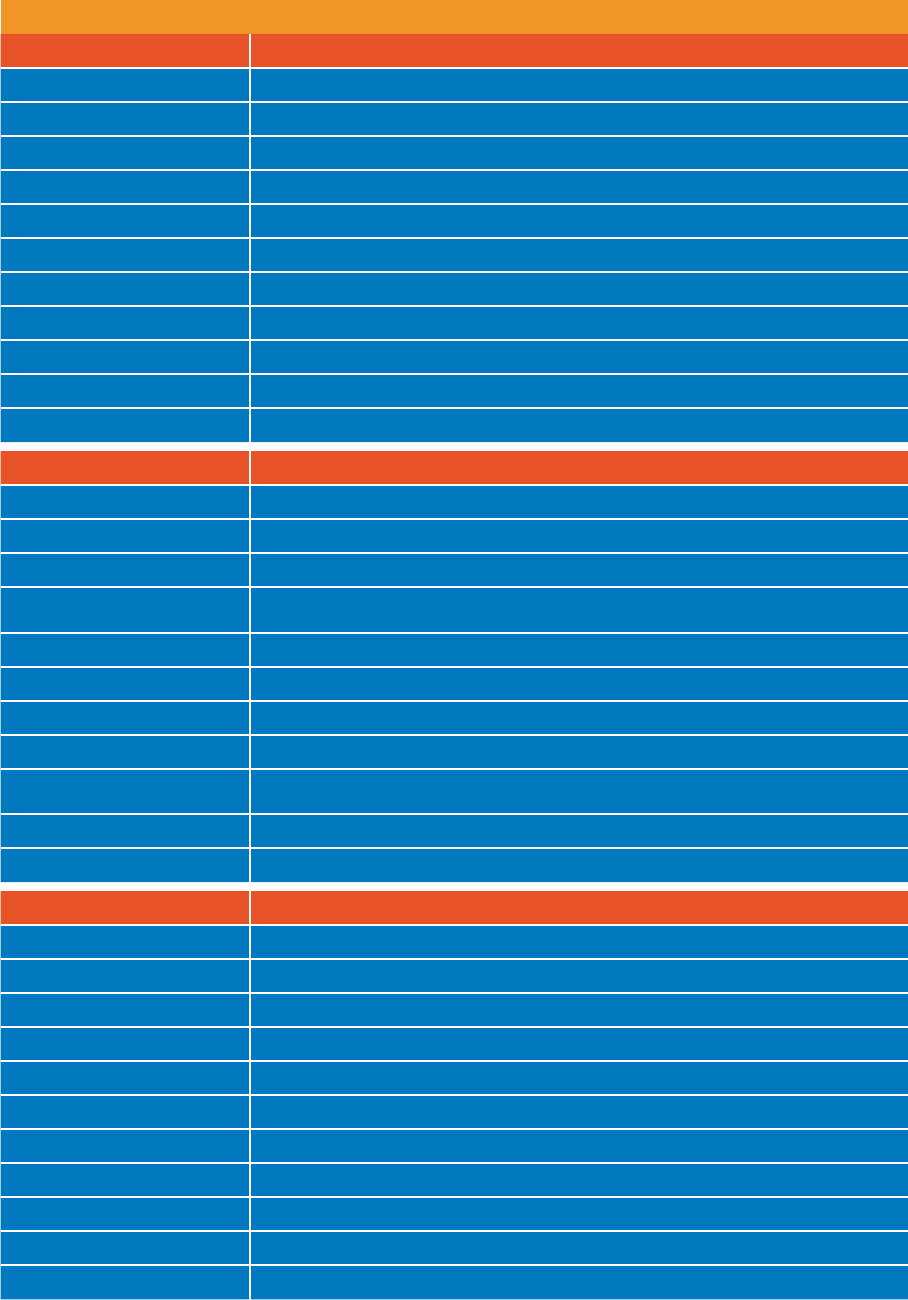

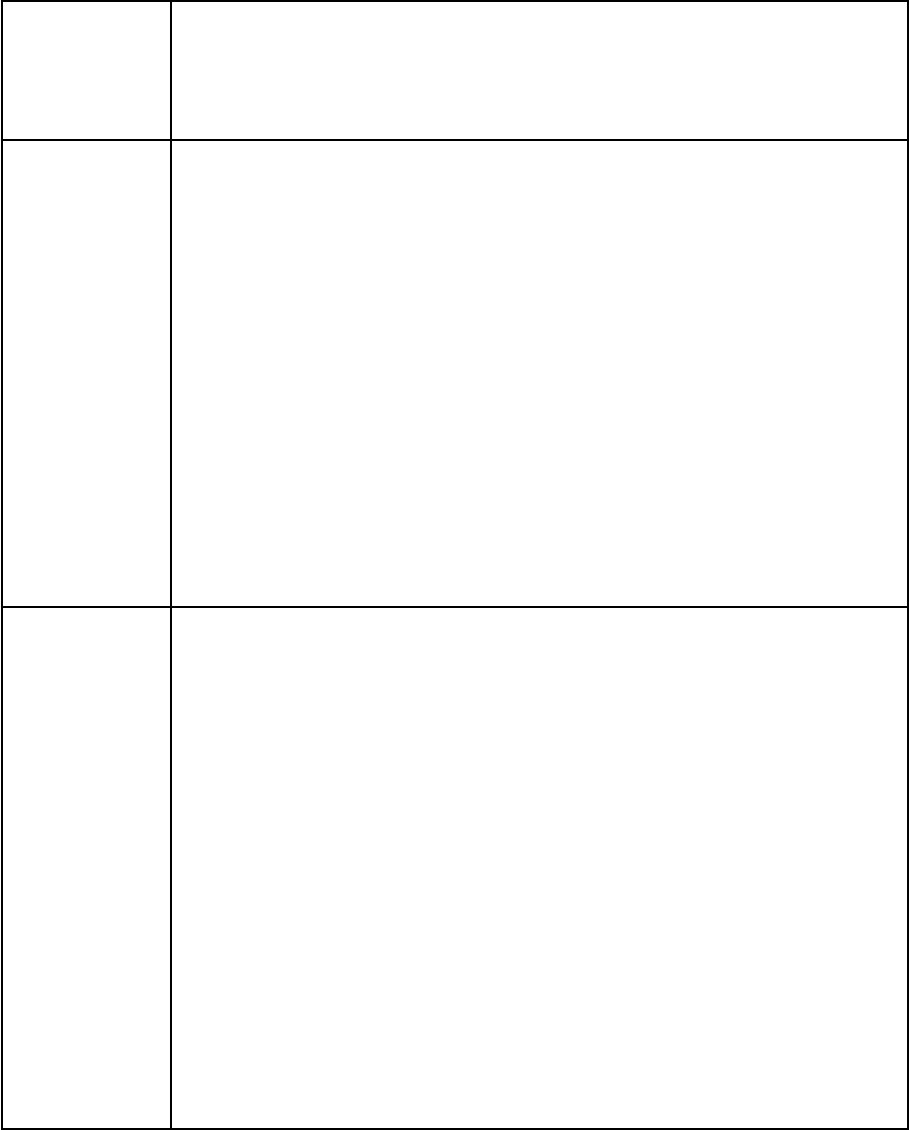

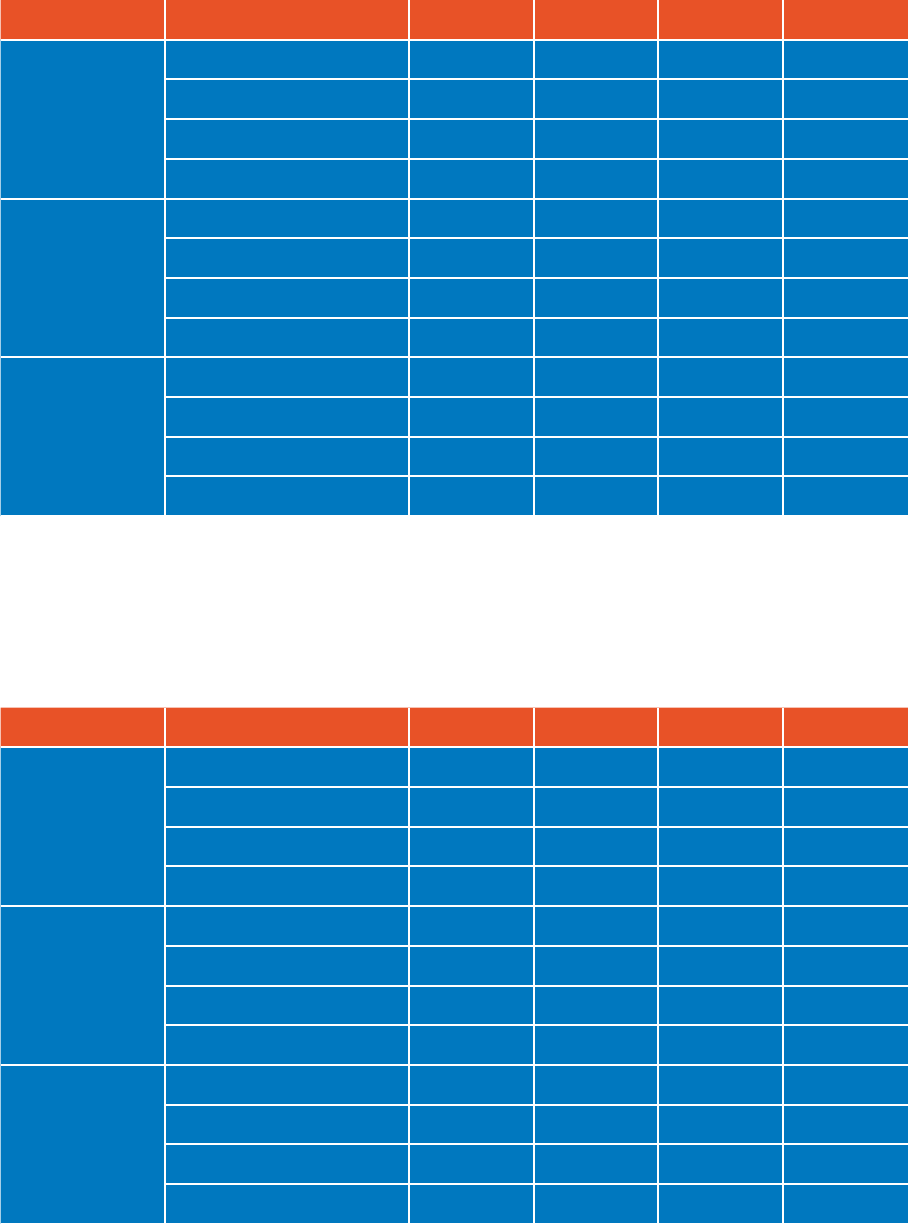

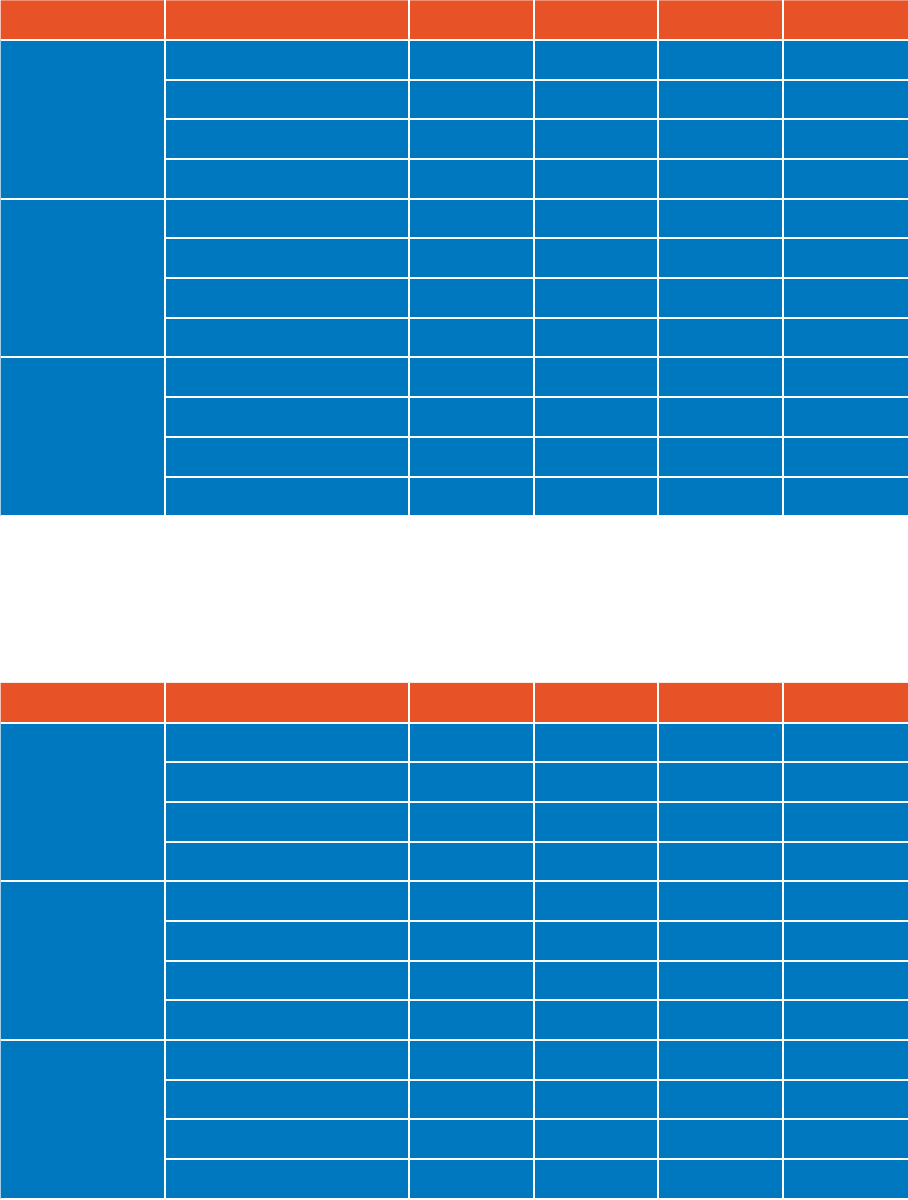

Video games impact, 2019

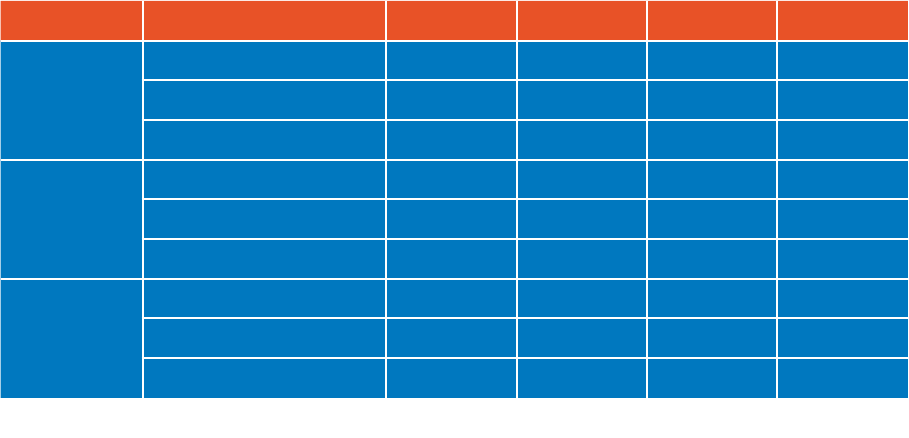

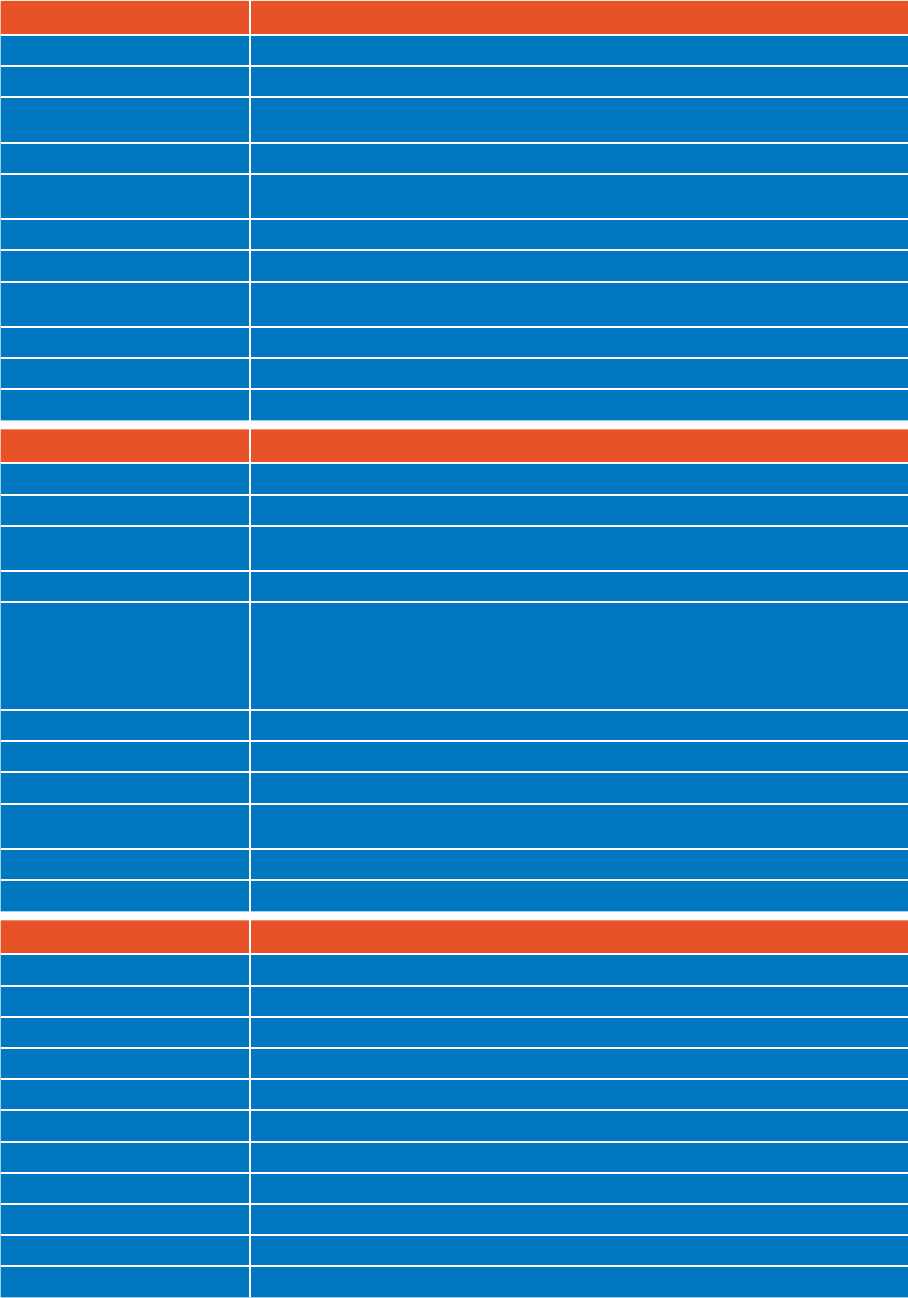

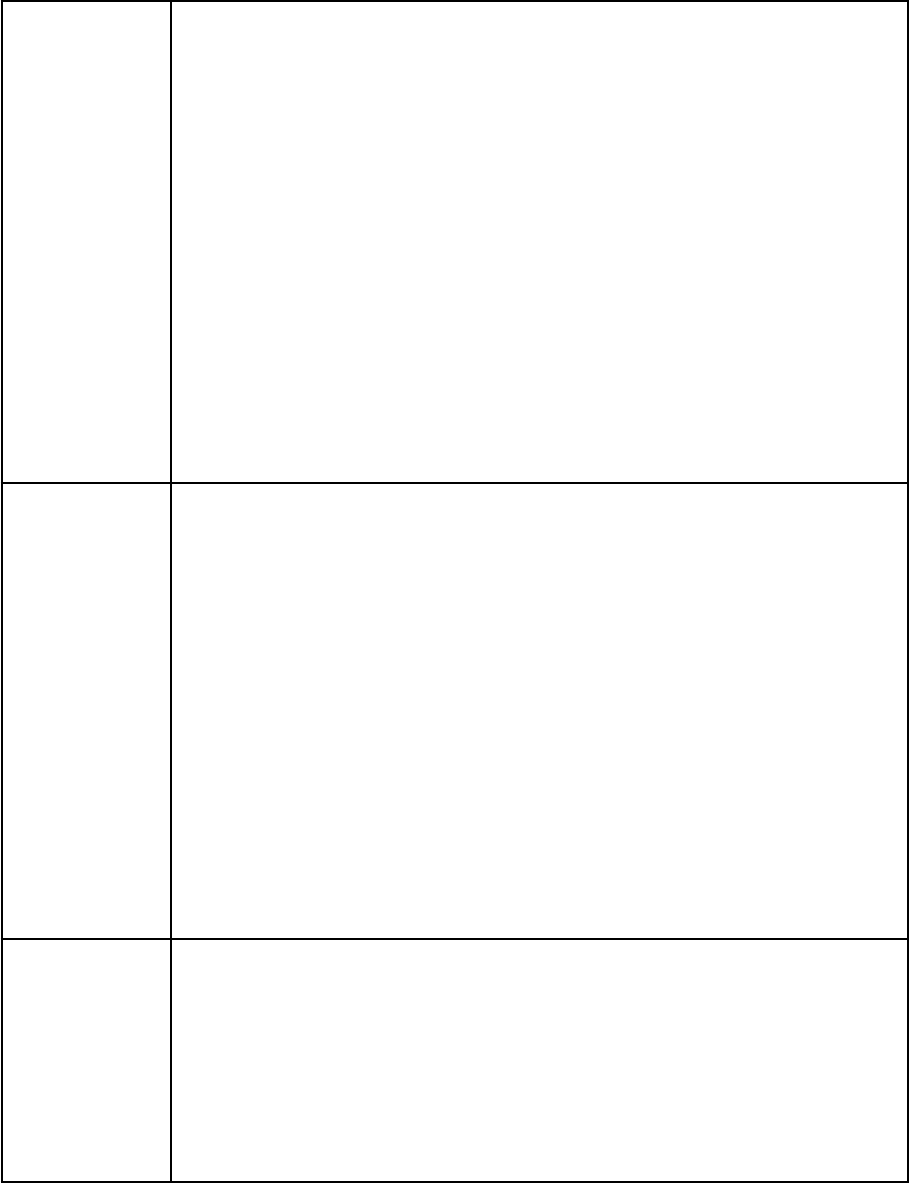

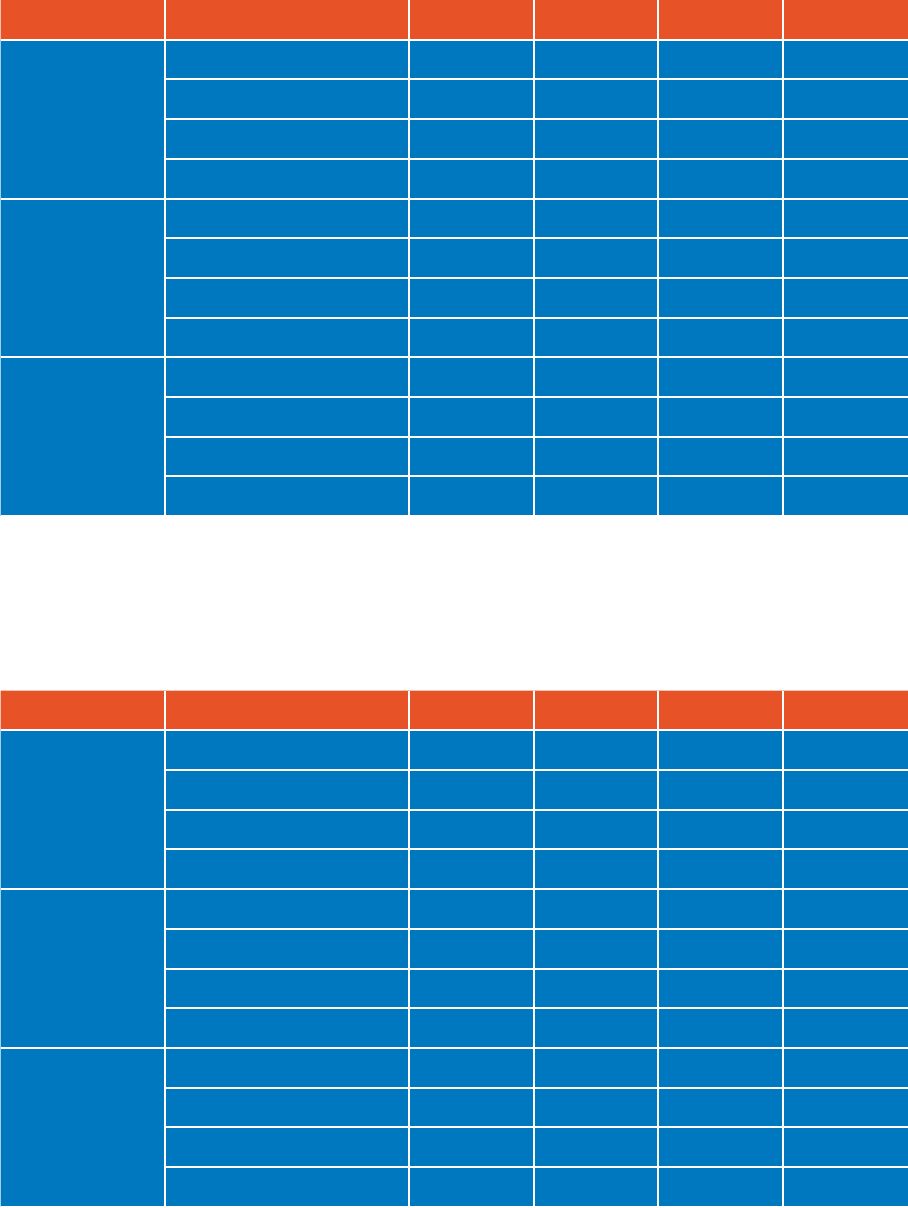

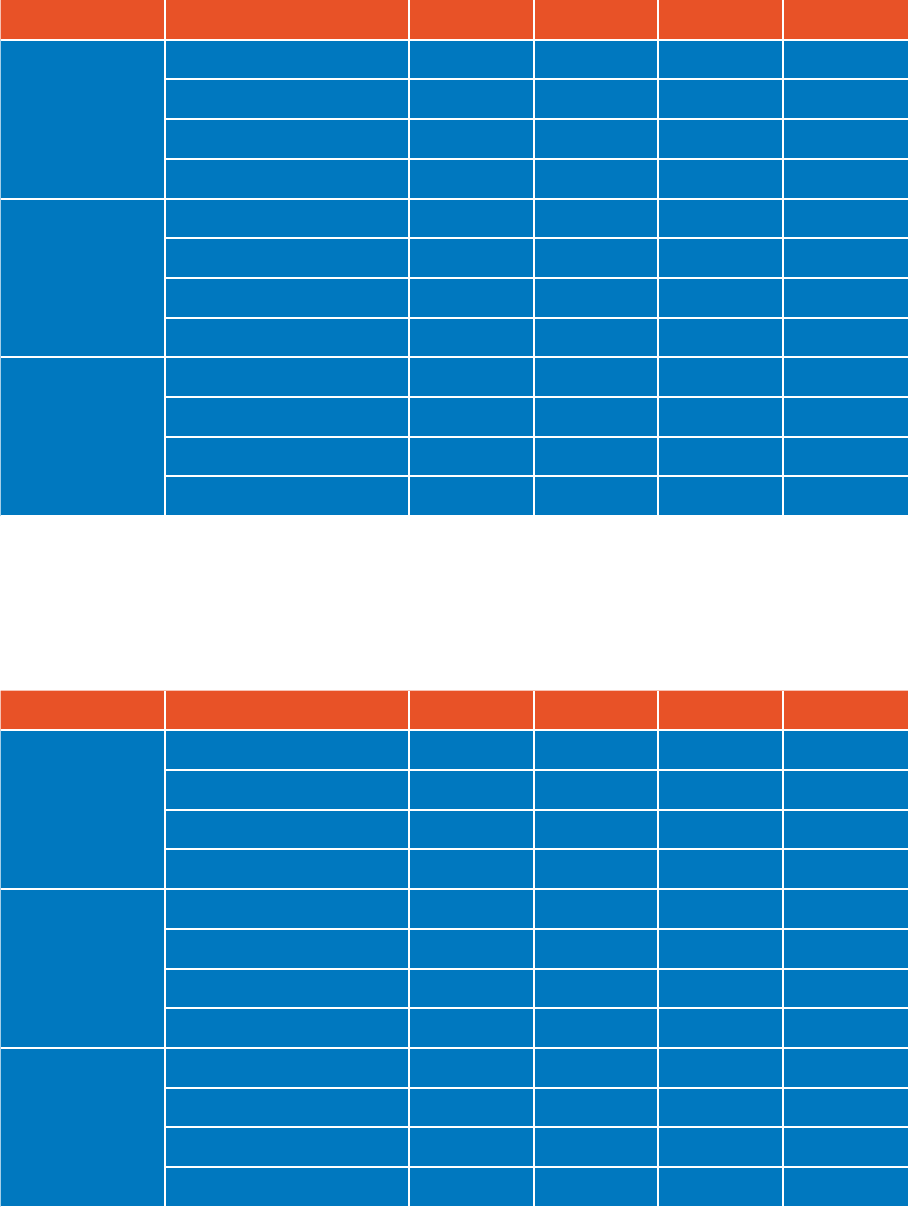

The impact of the film and high-end television tax reliefs UK-wide, 2017-2019

1. Context

2. Key findings

2.1. Delivering growth in production and development investment

2.2. Driving inward investment

2.3. Growth in employment

2.4. Expanding the economy

2.5. Delivering productivity

2.6. Providing return on investment

2.7. Supporting innovation

2.8. Growth in UK film and television studios

2.9. The impact of the film and high-end television tax reliefs UK-wide

2.10. The ripple effect of film and high-end television production

2.11. Delivering wider benefits

2.12. Notes on economic impact methodology

2.13. Key findings by sector

2.13.1. Film

2.13.2. High-end television

2.13.3. Video games

2.13.4. Animation programmes

2.13.5. Children’s television programmes

2.13.6. Visual effects

2.14. Global comparison of production incentives for film, television and

video games

2.15. Findings as a benchmark in the COVID-19 era

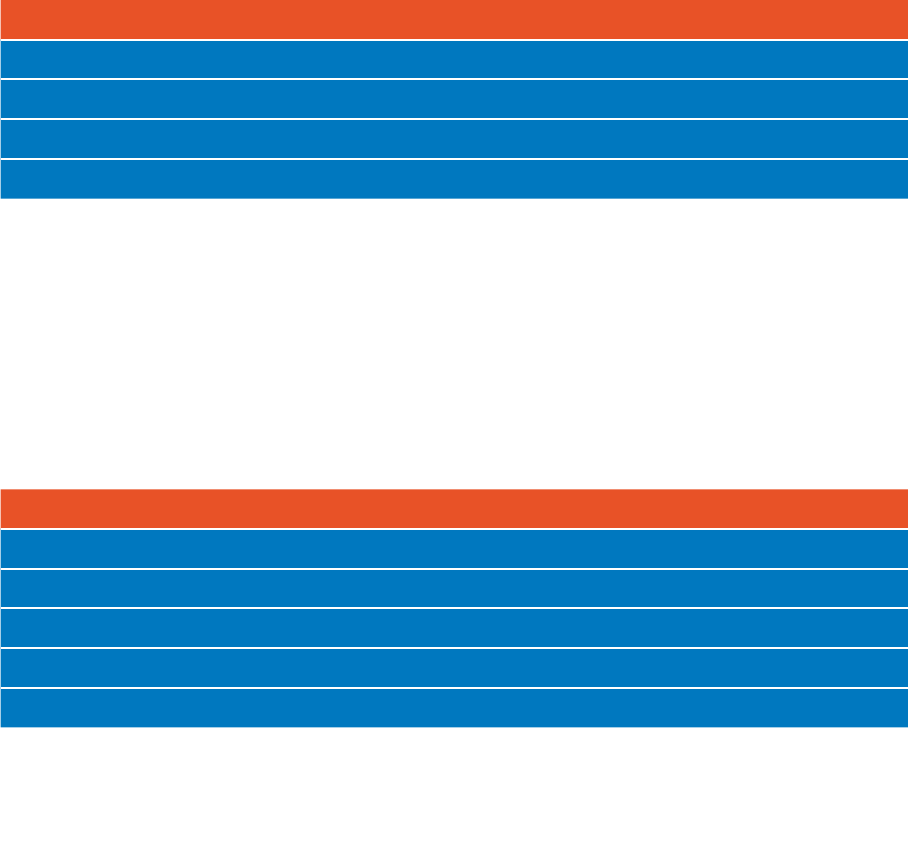

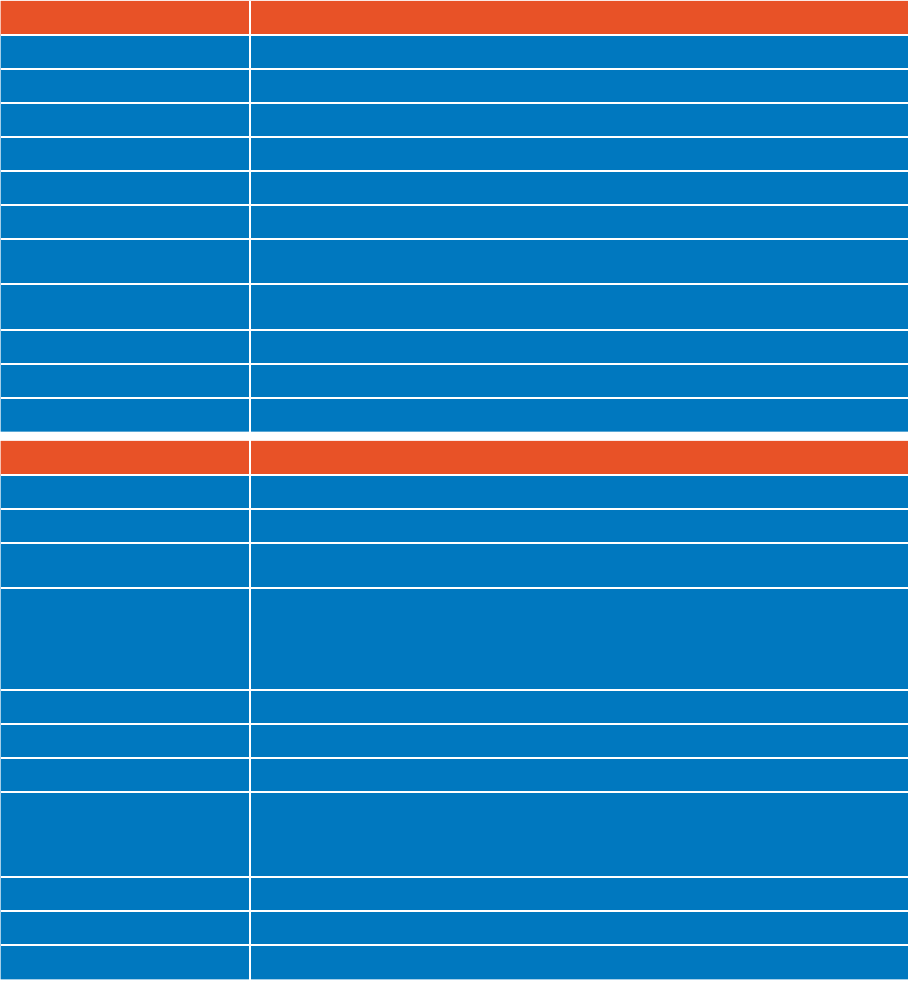

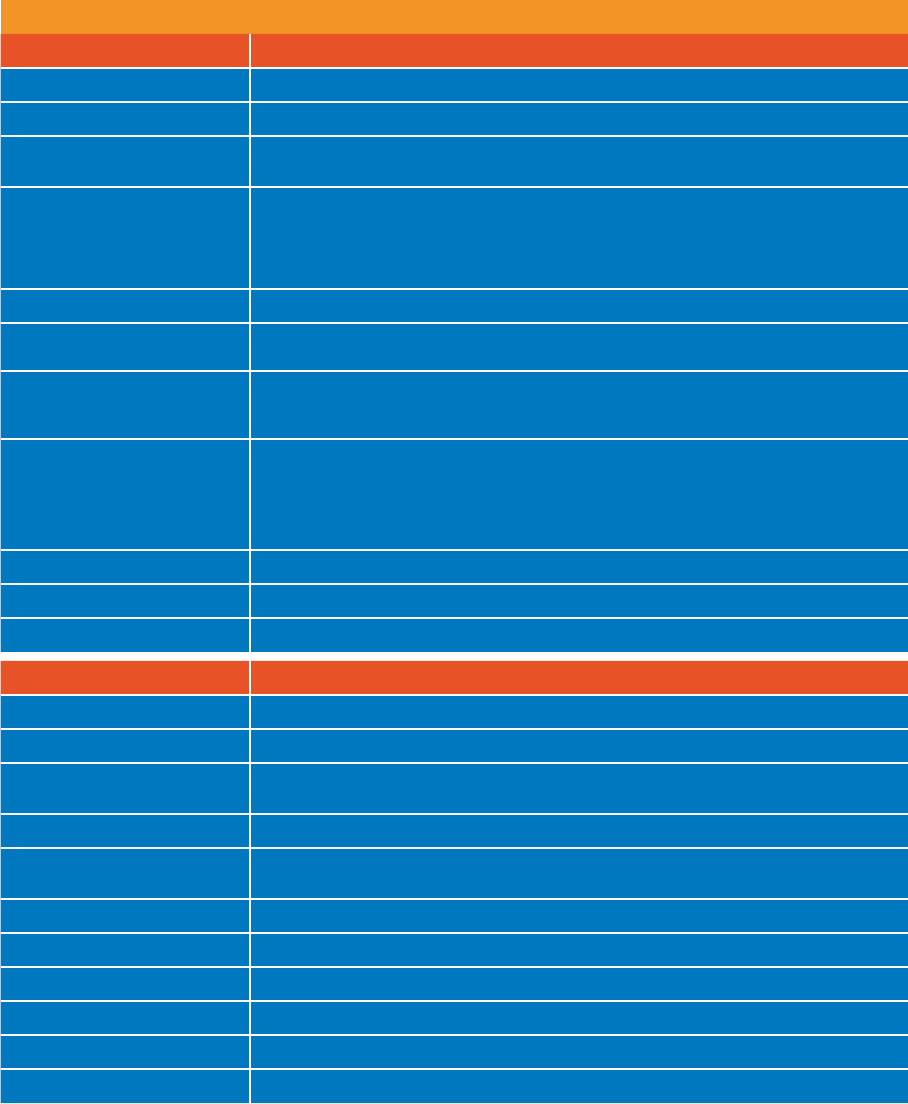

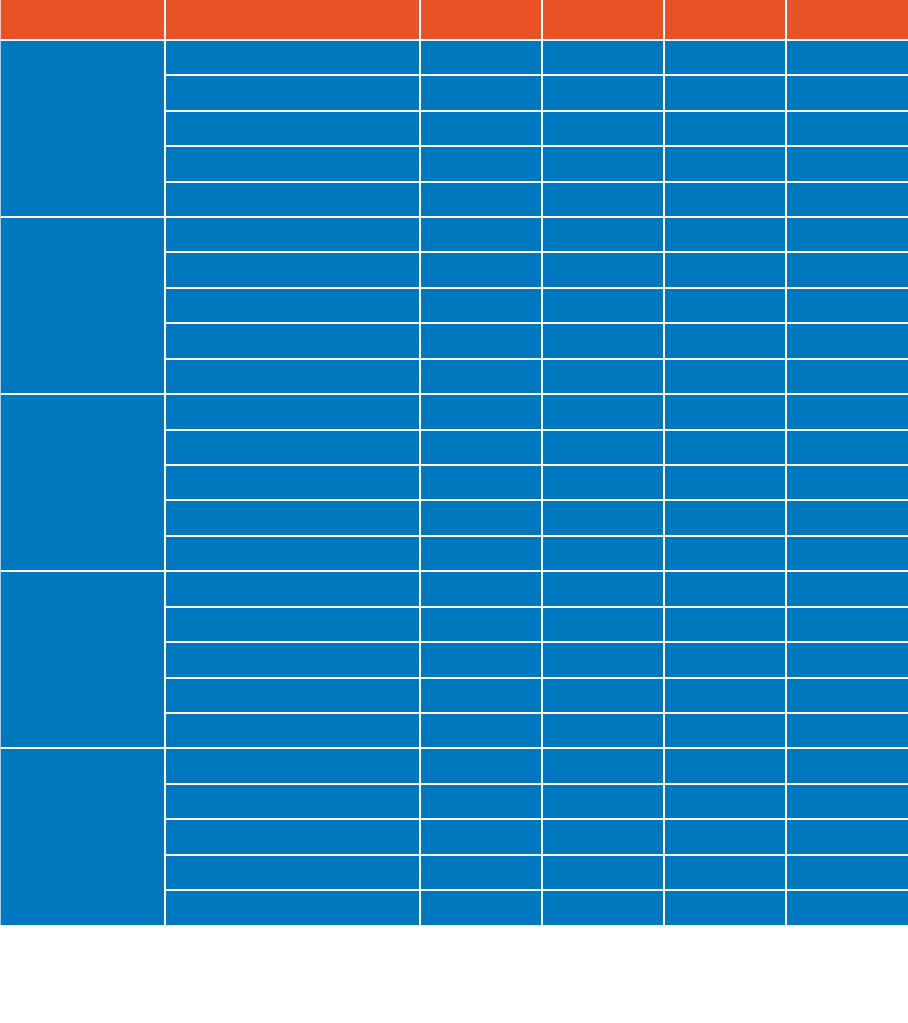

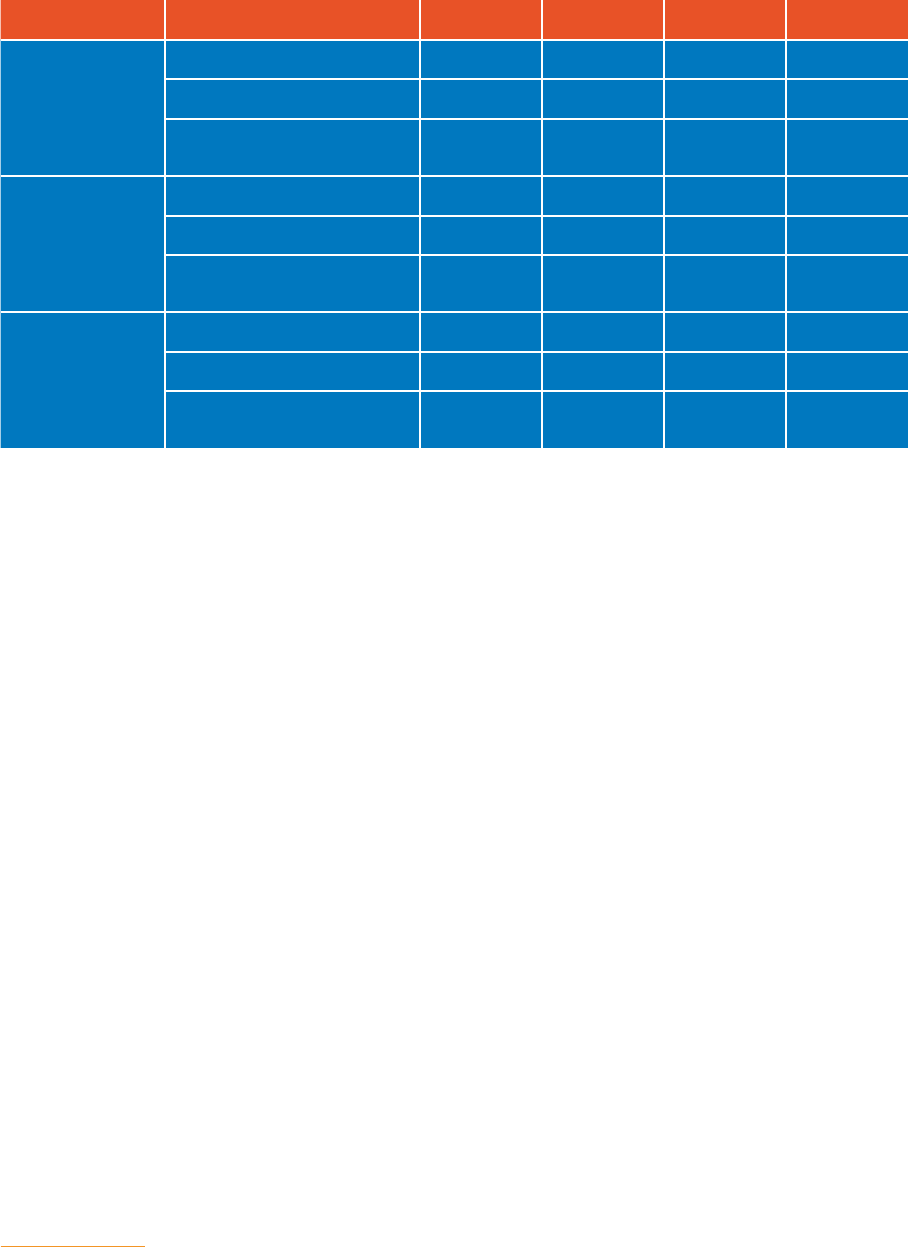

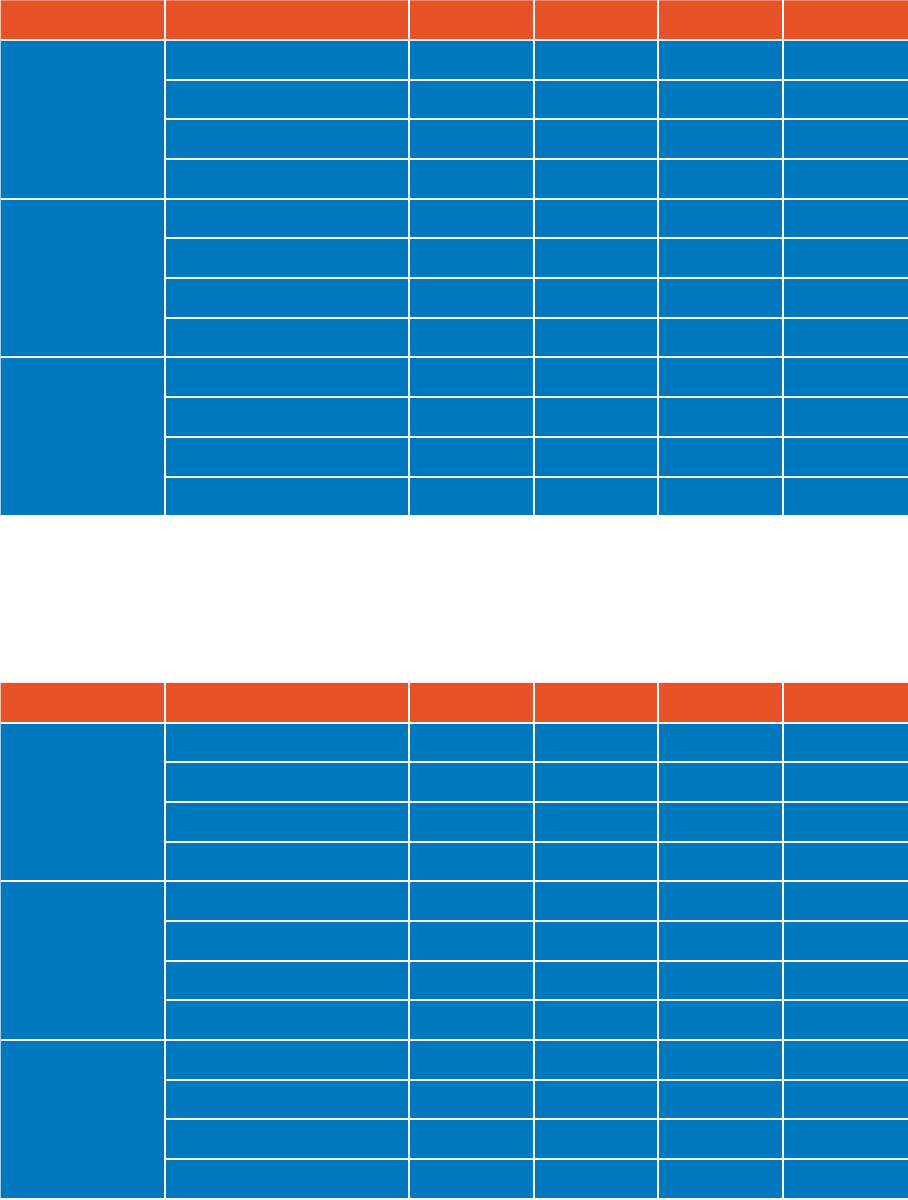

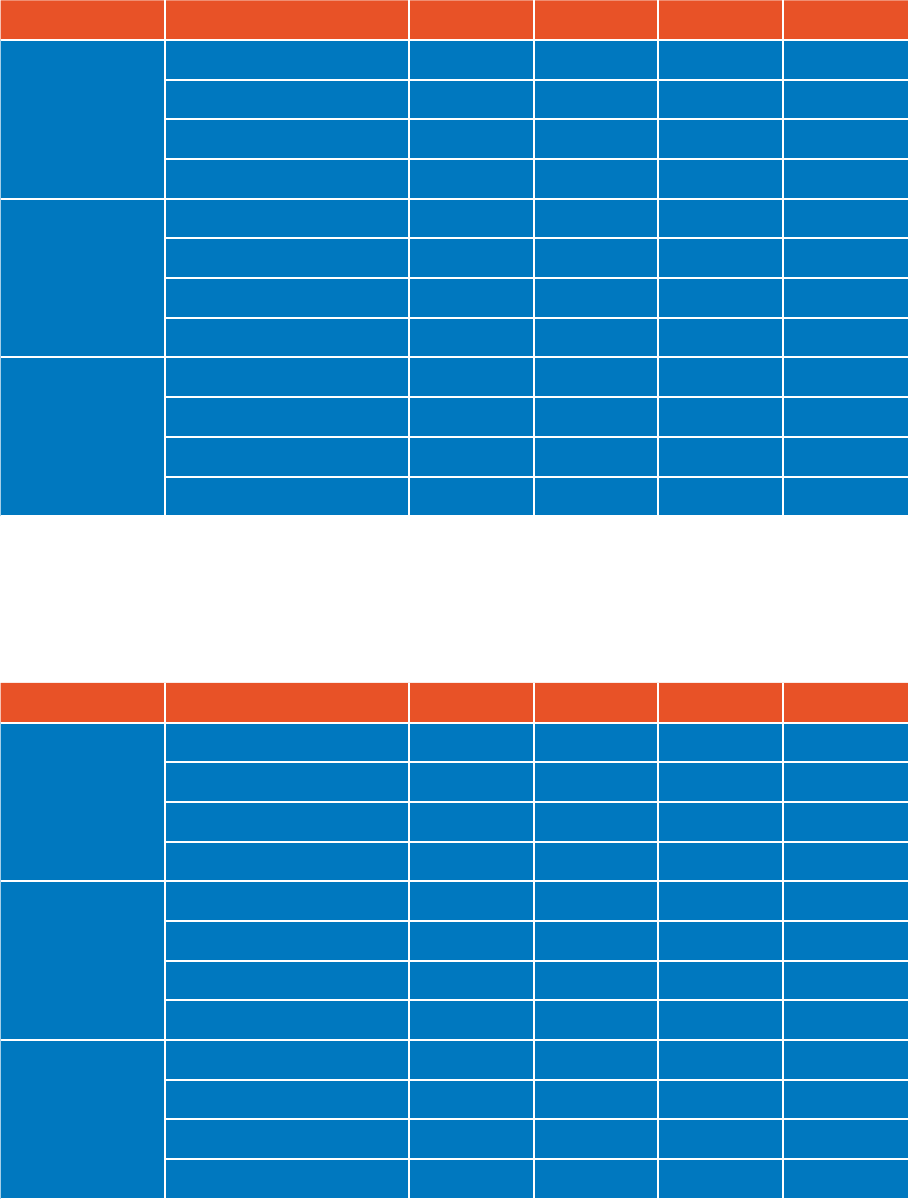

Key economic findings, 2016-2019

3. Introduction

3.1. Study scope

3.2. Background

3.3. Aims of the study

3.4. Differences from previous studies

3.5. Definitions of the UK screen sectors

3.5.1. Film

3.5.2. High-end television

3.5.3. Video games

3.5.4. Animation programmes

3.5.5. Children’s television programmes

8

9

12

13

14

15

16

18

19

21

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

29

30

30

31

31

32

33

33

34

35

37

38

39

39

40

40

41

42

42

42

43

43

2

Contents

3.6. UK tax reliefs and the definition of qualifying projects

3.7. The areas of economic impact

4. The film sector

4.1. Context and key findings

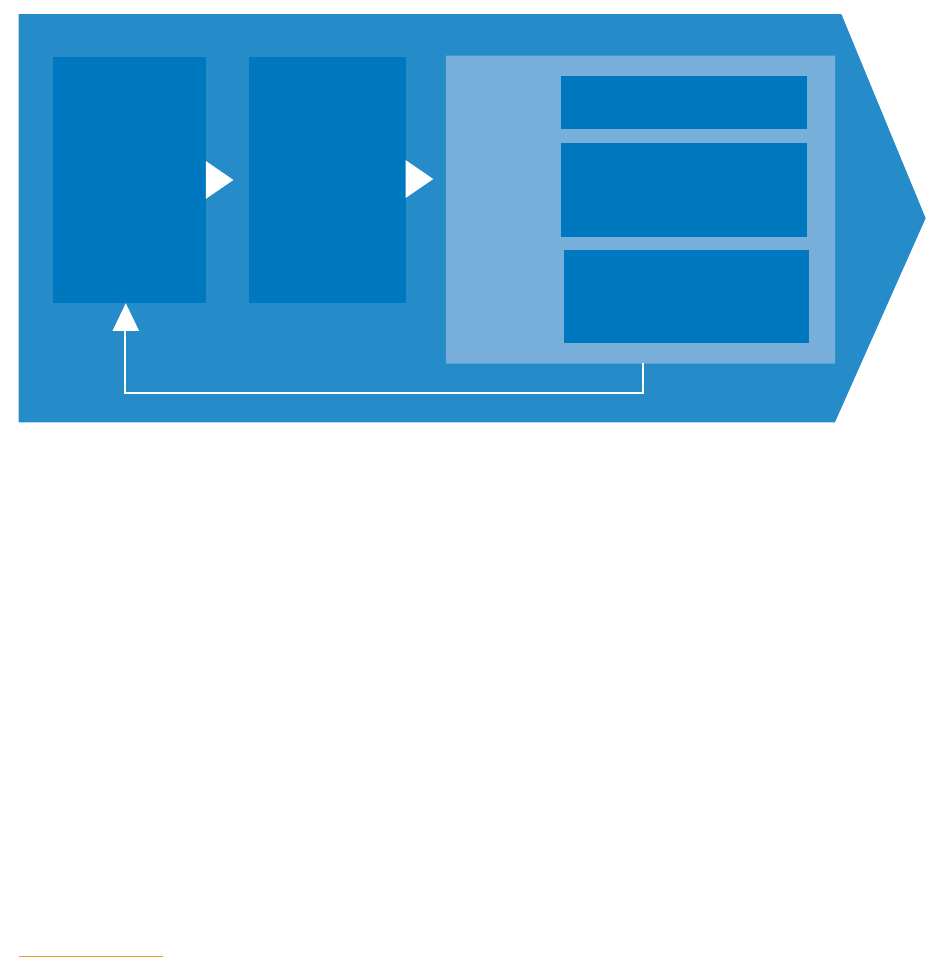

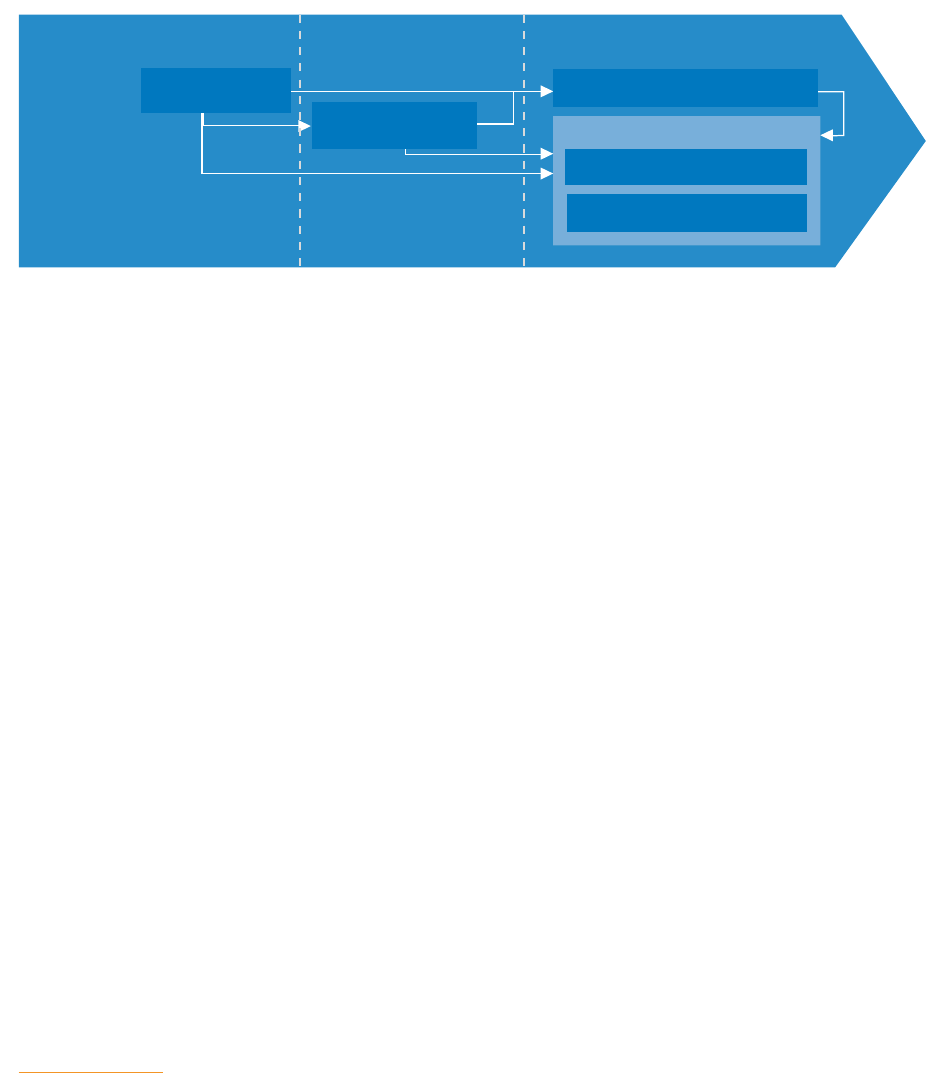

4.2. Value chain overview

4.3. Direct impact

4.3.1. Production

4.3.2. Distribution

4.3.3. Cinema exhibition

4.3.4. Secondary windows

4.3.5. Summary of direct economic impact

4.3.6. International trade

4.4. Total economic impact

4.5. Spillover impacts

4.5.1. Inbound tourism

4.5.2. Merchandise

4.5.3. UK brand promotion

4.5.4. Summary

4.6. Overall economic contribution

4.7. Impact of Film Tax Relief

5. The high-end television sector

5.1. Context and key findings

5.2. Value chain overview

5.3. Direct impact

5.3.1. Production

5.3.2. Television broadcast

5.3.3. Distribution

5.3.4. Video platforms

5.3.5. Summary of direct economic impact

5.4. Total economic impact

5.5. Time series statistics

5.6. Spillover impacts

5.6.1. Inbound tourism

5.7. Overall economic contribution

5.8. Impact of High-end Television Tax Relief

6. The video games sector

6.1. Context and key findings

6.2. Value chain overview

6.3. Direct impact

6.3.1. Development

6.3.2. Publishing

6.3.3. Digital retail

6.3.4. Physical retail

6.3.5. Summary of direct economic impact

6.4. Total economic impact

6.5. Spillover impacts

6.5.1. Merchandising and events

44

44

46

47

48

49

49

53

57

62

66

67

70

72

73

74

74

76

77

78

80

81

82

83

83

85

87

88

89

90

92

93

93

94

95

97

98

99

101

101

102

104

105

106

107

108

108

3

109

110

111

111

113

114

115

116

116

118

119

120

121

122

123

123

126

128

128

130

131

131

132

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

140

140

142

143

143

146

147

149

150

150

152

153

157

6.5.2. Esports

6.5.3. Summary

6.6. Overall economic contribution

6.7. Impact of Video Games Tax Relief

7. The animation programme sector

7.1. Context and key findings

7.2. Value chain overview

7.3. Direct impact

7.3.1. Production

7.3.2. Television broadcast

7.3.3. Distribution

7.3.4. Video platforms

7.3.5. Summary of direct economic impact

7.4. Total economic impact

7.5. Spillover impacts

7.5.1. Merchandise

7.5.2. Tourism

7.6. Overall economic contribution

7.7. Impact of Animation Tax Relief

8. The children's television programme sector

8.1. Context and key findings

8.2. Value chain overview

8.3. Direct impact

8.3.1. Production

8.3.2. Television broadcast

8.3.3. Distribution

8.3.4. Video platforms

8.3.5. Summary of direct economic impact

8.4. Total economic impact

8.5. Spillover impacts

8.6. Overall economic contribution

8.7. Impact of Children’s Television Tax Relief

9. The visual effects sector

9.1. C on tex t

9.2. Direct impact

9.3. Total economic impact across value chain – tax relief-supported

9.4. Overall economic contribution

10. The UK nations and England's regions - The impact of the film and

high-end television tax reliefs UK-wide

10.1. O ve r view

10.2. Outline of approach

10.3. Impacts

10.3.1. High-end television

10.3.2. Film

4

11. The ripple effect - Measuring the micro-economic impact of film and

television production spending across business sectors

11.1. Over v i ew

11.2. Breadth of impact across business sectors

11.2.1. Screen production-specific

11.2.2. Business support

11.2.3. Construction

11.2.4. Digital services

11.2.5. Real estate

11.2.6. Travel and transport

11.2.7. Hospitality and catering

11.2.8. Finance and legal

11.2.9. Fashion and beauty

11.2.10. Music and performing arts

11.2.11. Power and utilities

11.2.12. Safety and security

11.2.13. Training and education

11.2.14. Health and medical

11.2.15. Local labour miscellaneous

11.3. Impacts – overall

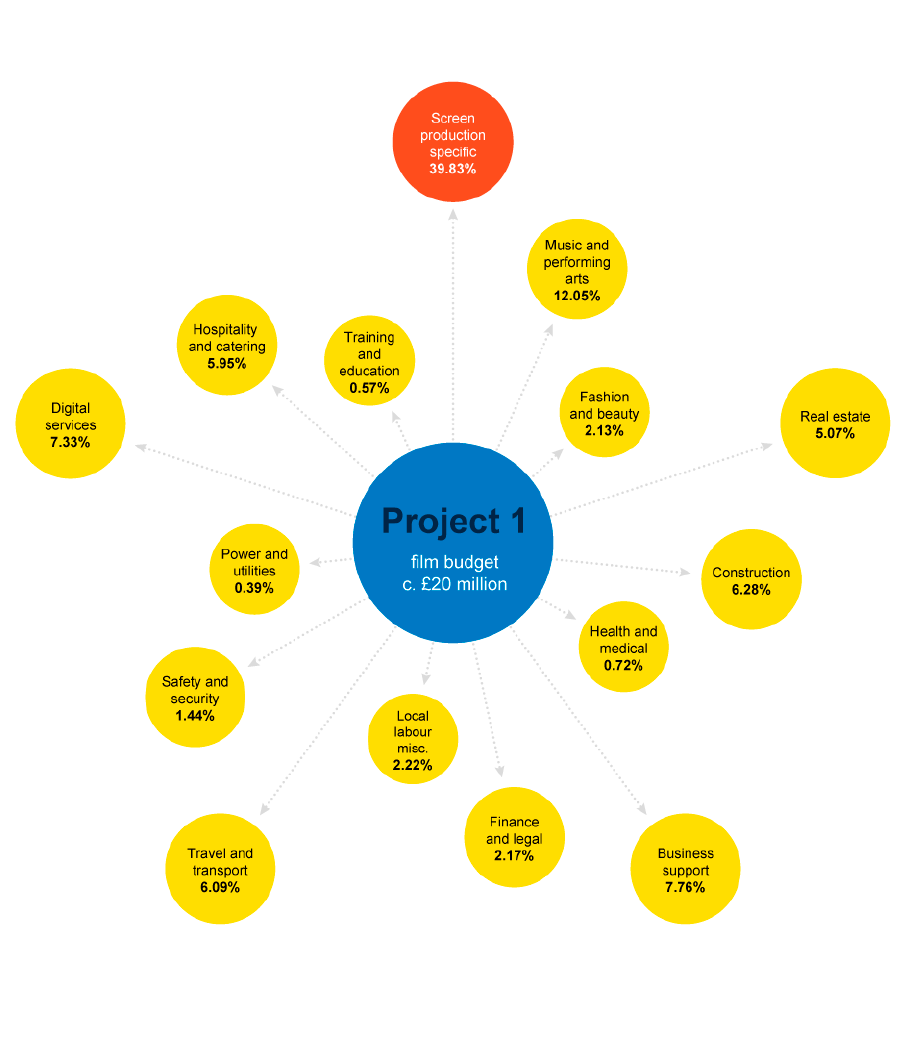

11.4. Project one

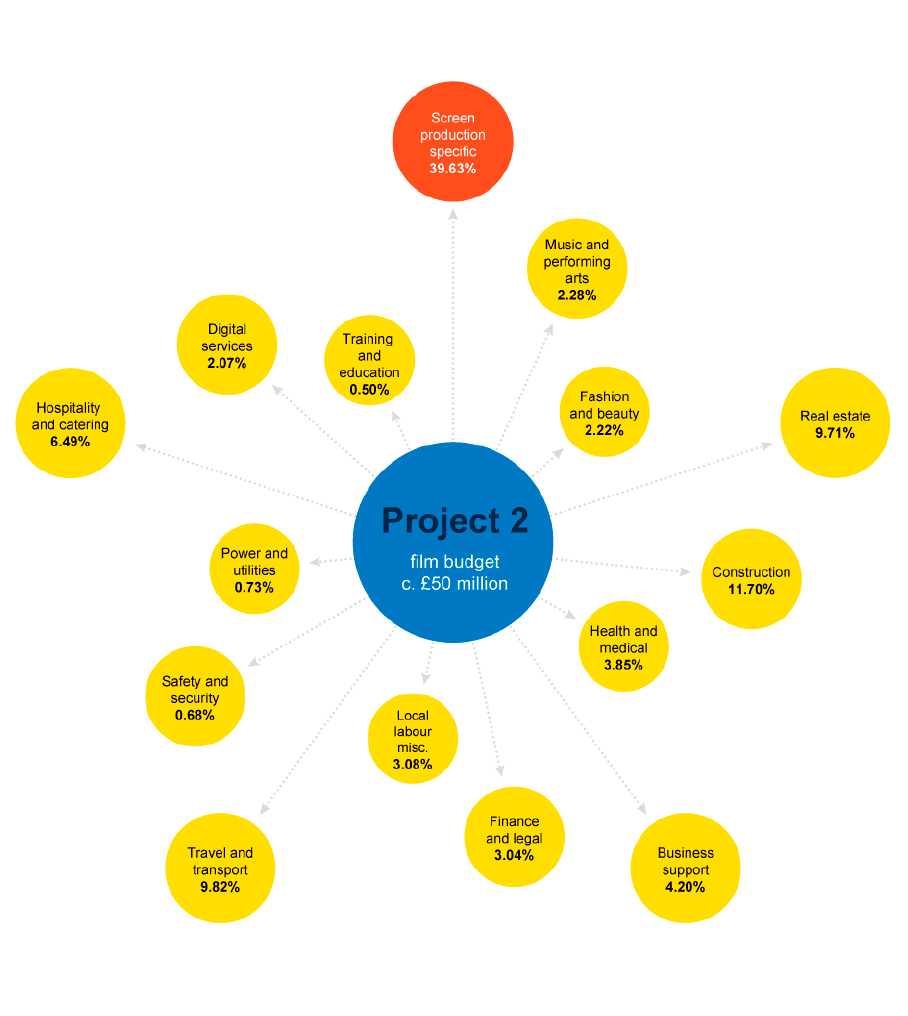

11.5. Project two

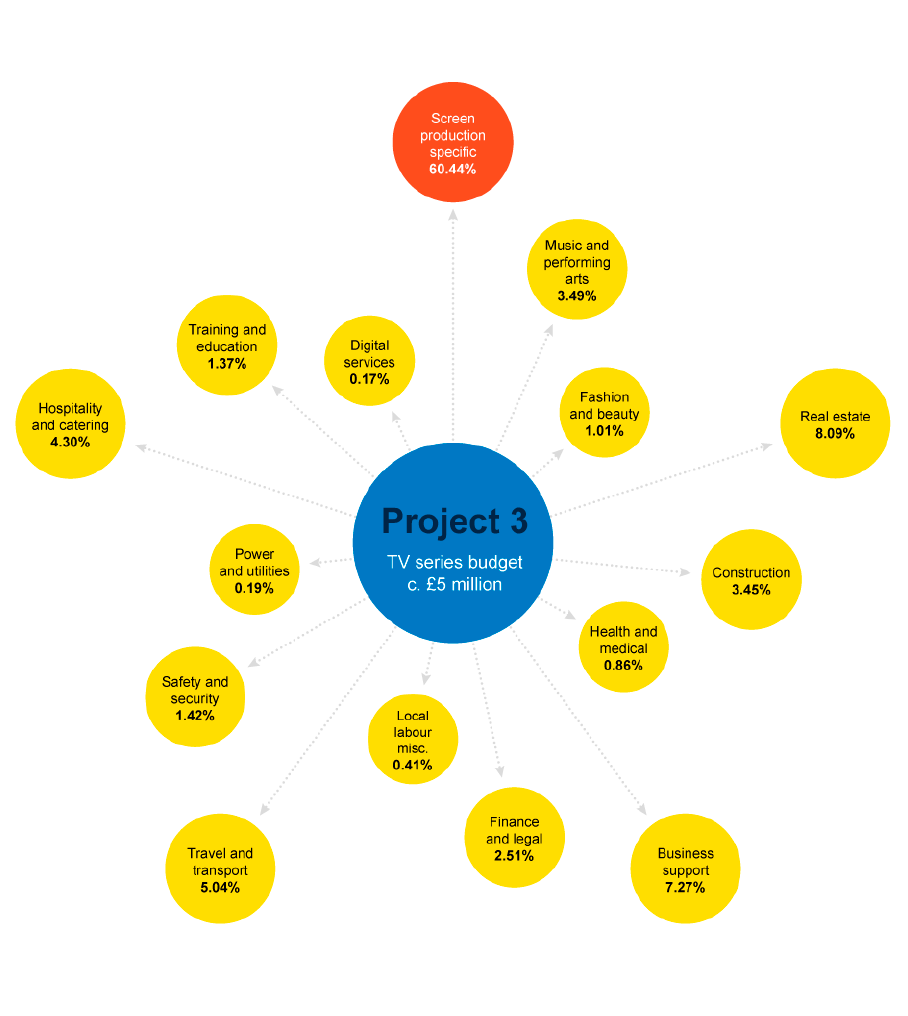

11.6. Project three

12. Comparison of global production incentives for film, television and

video games

12.1. Contex t

12.2. Cultural tests and the European Union’s 80% limit

12.3. Best practice

12.4. Summary of comparable analysis

12.5. Summary of the UK’s Creative Sector Tax Reliefs

12.6. Australia

12.7. Canada

12.7.1. O n t a r i o

12.7.2. Quebec

12.7.3. British Columbia

12.8. France

12.9. Germany

12.10. Greece

12.11. Hun gar y

12.12. New Zealand

12.12.1. VFX eligible formats

12.12.2. 5% uplift

12.13. Republic of Ireland

12.14. Spain

12.15. United States

12.15.1. California

12.15.2. Georgia

12.15.3. Louisiana

12.15.4. New Jersey

161

162

163

163

164

164

164

164

164

164

165

165

165

165

165

166

166

166

166

167

169

171

173

174

175

176

177

187

187

188

189

189

189

189

190

190

190

191

191

192

192

192

193

193

194

194

194

5

195

196

197

198

199

199

202

203

205

207

209

211

213

214

216

218

219

220

220

222

224

225

227

229

230

236

236

237

238

238

239

241

242

245

245

247

248

248

250

252

254

256

258

12.15.5. New Mexico

12.15.6. Pennsylvania

13. UK film and television studio analysis

13.1. O ve r view

13.2. The importance of film and television studios

13.3. Defining and calculating studio investment

14. Screen sector innovation

14.1. Jellyfish Pictures

14.2. StoryFutures and StoryFutures Academy

14.3. Virtual production

14.4. Future Screens NI and Screen Media Innovation Lab

14.5. Media Molecule’s Dreams

15. Conclusions

15.1. Total economic impact

15.2. Impact in UK nations and England’s regions

15.3. Overall economic contribution

16. Appendix 1 - Total video games sector impact

16.1. Direct impact

16.1.1. Deve lop men t

16.1.2. Publishing

16.1.3. Digital retail

16.1.4. Physical retail

16.1.5. Summary

16.1.6. Total economic impact

16.1.7. Impact in UK nations and England’s regions

16.2. Spillover impacts

16.2.1. Merchandise and events

16.2.2. Esports

16.2.3. Summary

16.3. Overall economic contribution

16.4. Corporate investments and acquisitions

17. Appendix 2 - Total VFX sector

17.1. Direct impact

17.1.1. Value chain impact

17.2. Overall economic contribution

18. Appendix 3 - Economic contribution methodology

18.1. Direct impact

18.1.1. Film sector

18.1.2. High-end television sector

18.1.3. Video games sector

18.1.4. Animation programme sector

18.1.5. Children’s television sector

18.1.6. VFX sector

6

259

259

260

261

261

261

262

263

265

266

266

269

270

270

271

272

275

276

279

281

283

285

286

289

291

293

294

296

307

317

18.2. Indirect and induced impacts (multiplier effects)

18.2.1. Indirect impacts

18.2.2. Induced impacts

18.3. Total economic impact

18.4. Additionality and return on investment

18.4.1. Gross additionality

18.4.2. About the survey

18.4.3. Net additionality

18.4.4. Sensitivity analysis

18.5. Audience analysis and derivation of economic shares

18.5.1. Calculation of the economic share in 2016

18.5.2. Calculation of the economic share for 2017 to 2019

18.6. Adjusted economic shares

18.6.1. Distribution

18.6.2. Video platforms

18.7. Tax revenue impacts

19. Appendix 4 - Additional data tables

19.1. Film Tax Relief

19.2. High-end Television Tax Relief

19.3. Animation Tax Relief

19.4. Children’s Television Tax Relief

20. Appendix 5 - Historical analysis

20.1. Film Tax Relief

20.2. High-end Television Tax Relief

20.3. Animation Tax Relief

21. Appendix 6 - Lists of figures and tables

21.1. List of figures

21.2. List of tables

22. Appendix 7 - Bibliography

23. Appendix 8 - Glossary

7

8

The BFI would like to thank all those involved in the production of this

report, in particular those in DCMS, HM Treasury and HMRC who have

provided valuable input to the scope, outputs and, in particular, advice on

the methodology.

We would also like to thank all members of the screen sectors who have

provided data and information in order for us to compile the granular detail

that underpins the findings and to those who have worked tirelessly to

check and validate the findings.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Olsberg•SPI

Steve Clark-Hall

Leon Forde

Kayleigh Hughes

Claire Lamarra

Jonathan Olsberg

Joe Stirling Lee

Neil Watson

Nordicity

Dustin Chodorowicz

Balvinder Chowdhary

Shruti Srinivasan

John Yun

AudienceNet

Karen Mulvee

Incorporate Design

Ed Bowes

Jo McIlvenna Ltd

Jo McIlvenna

Members of the project

steering group

Neil Hatton, UK Screen Alliance

Luke Hebblethwaite, Ukie

John McVay, Pact

Kate O’Connor, Animation UK

Samantha Perahia, British Film

Commission

Andrew Smith, Pinewood Studios

Jo Twist, Ukie

Richard Wilson, TIGA

Adrian Wootton, British Film

Commission/Film London

Members of the Screen

Industry Research and

Statistics Advisory Group

Charlie Bloye

Caterina Branzanti

Barry Dixon

James Duvall

Eliza Easton

Luke Hebblethwaite

Hana Lewis

Kate O’Connor

Emily Oyama

Faith Taylor

Gillian Youngs

BFI

Ian Cade

Rishi Coupland

Emily Dickie

Harriet Finney

Harriet Francis

Yvonne Harris

Julia Lamaison

Anna Mansi

Nick Mason Pearson

Paul McEvoy

Tina McFarling

Claire O’Brien

Stephanie Redstone

John Sandow

Darren Wood

9

The UK’s creative industries are genuinely world-class, projecting our values

and influence around the world. And whether it is a small theatre in a market

town, an independent cinema or a nationally significant body, they bring joy

and enrichment to our day-to-day lives in all our communities.

So, it is great to see that since the last edition of this report in 2018, the UK’s

unique, world-class creative talent has continued to produce work of the

highest quality.

Whether it is with the development of interactive and immersive games

such as Dreams, award-winning films such as The Favourite, the popular

animation of The Gruffalo, or high-end TV productions such as His Dark

Materials, the UK creative industries have underlined their positions as

global leaders.

2020 and 2021 have been challenging years for the whole country, including

our creative industries which are a vital part of the cultural fabric of the

UK. That is why the Government stepped in. Alongside the Coronavirus

Job Retention Scheme (CJRS) and the Self-Employed Income Support

Scheme, which have protected 11.6 million jobs and supported nearly three

million self-employed individuals respectively, the Government has launched

initiatives such as the £500 million Film & TV Production Restart Scheme,

which has helped productions to continue in the absence of insurance for

COVID-19 related risks, protecting over 80,000 jobs. The Government is also

supporting apprenticeship training, offering employers over 600 employer-

designed, high quality apprenticeships to choose from. This includes key

roles in the creative sector such as Post-Production Engineer, VFX Artist and

Props Technician, helping people of all ages and at all career stages gain

valuable skills and retrain.

The Government will continue to support our highly-skilled and innovative

creative industries through creative sector tax reliefs. In 2020-21 alone the

film, TV, video games, children's TV and animation industries reliefs provided

more than £1.2 billion of support to over 2,000 projects. These reliefs have

also helped to spur a new wave of private investment to develop major

production hubs and centre points for high quality crew and studio space all

over the UK, from Belfast to Buckinghamshire, supporting tens of thousands

of jobs.

I would like to thank the BFI for its efforts in continuously championing the

screen sectors and supporting them through the pandemic.

Looking to the future, I am confident that the creative industries in the UK will

continue to prosper, compete internationally and be a glittering showcase for

British culture.

The Rt Hon Rishi Sunak MP

Chancellor of the Exchequer

FOREWORD

10

This second edition of the Screen Business report provides a comprehensive

analysis of the value of the screen sector tax reliefs to the industry and to the

wider UK economy. It shows the tax reliefs have been instrumental to how

UK made and developed film, high-end, children’s and animation television

and video games have flourished since the reliefs were introduced.

In 2019 alone, these areas of screen production delivered £13.48bn to

the UK economy – a significant increase from £8.6 billion in 2016 – and

generated 218,790 jobs. The reliefs have also helped to attract significant

capital investment into the sector’s facilities and services, generating an

additional £3.60 billion in tax revenue to the Exchequer, as well as driving

business for industries such as merchandising and tourism.

The reliefs are also vital to UK creativity and culture. We make high quality

film, television and screen content that is enjoyed by audiences at home

and around the world, demonstrating our talent and innovation in creative

storytelling, and the skills and expertise of our world-class crew, cast, video

games developers and production businesses.

Over the period of the report and running on into this year’s recovery period,

the sector has been hard at work making international blockbusters such

as Mission: Impossible – Fallout, the new Indiana Jones and Wonka and

independent UK films such as The Personal History of David Copperfield,

Yardie, Mogul Mowgli and Rocks. UK companies have created a string of

global television hits from His Dark Materials, Peaky Blinders and Line of Duty

to the animated Peppa Pig, Shaun the Sheep and Sarah and Duck, and

programmes for children such as The Worst Witch and Horrible Histories.

UK video games developers are also behind some of the world’s biggest

selling titles such as Grand Theft Auto V, Batman: Arkham Knight, the LEGO

and Forza Horizon series and Formula One games.

The report’s analysis concludes before the onset of the pandemic (the

last point at which full data is available), which globally brought many

industries to a halt. Since then, the BFI’s latest statistics have shown a

bounce-back in activity, with £1.24 billion of film and high-end television

spend during the last quarter of 2020. This has only accelerated during

2021 and we are now on a trajectory to surpass pre-pandemic business

levels as we close in on £5 billion production spend solely on film and high-

end television over the past 12 months. The adjustment to the film tax relief

announced in the Government’s November 2021 Spending Review will

support the highly connected way that the film and HETV now work to fund

and produce content.

Screen Business has expanded its analysis in a number of areas to look in

more detail at the UK’s position in a growing and highly competitive industry

globally. For the first time, the report provides a detailed comparison of global

tax reliefs – other countries are now revising their reliefs to encourage specific

types of production. It illustrates the vital role the reliefs play in giving the UK

a competitive and stable market position in a growing and highly competitive

industry globally in which to develop and produce content, as well as

supporting the UK in developing and creating IP.

FOREWORD

11

The new UK Global Screen Fund, administered by the BFI on behalf of the

Government, was launched last year with the aim of boosting our exports,

UK co-productions and the UK’s development of international partnerships.

In recent years, the UK’s nations and England’s regions outside the

London area, have seen increasing amounts of film and high-end television

production generating economic growth and creating jobs. Multi-million

pound investments in expanding studio capacity across the UK have

also accelerated significantly, to meet the demand for production. Actual

production budget breakdowns in the report also demonstrate the ripple

effect spend on local business sectors that supply goods and services to film

and high-end television productions.

The analysis also takes a deeper dive into the UK’s world-leading VFX

sector and screen sector innovations, and the potential they hold for the UK

economy more widely.

This is all good news for the sector overall, however it is not without

significant challenges which have been thrown into sharp focus for

independent film production in the wake of accelerated production growth

- namely higher costs for Covid-safety, skills shortages being addressed

through the government and industry skills review, and a rapidly shifting

international landscape.

This report sets out to empower industry decision-makers in growing their

businesses, and policy-makers at every level of local, national and UK-wide

government in looking to create the best possible conditions for future

growth. The screen sectors are a huge economic asset to the UK and, with

the maintenance of the screen sector tax reliefs and continued investment in

nurturing diverse creative talent, skills and infrastructure by both Government

and industry alike, the screen sector is an engine primed to support the UK’s

economic recovery.

Ben Roberts

Chief Executive, British Film Institute

FOREWORD

12

SUMMARY

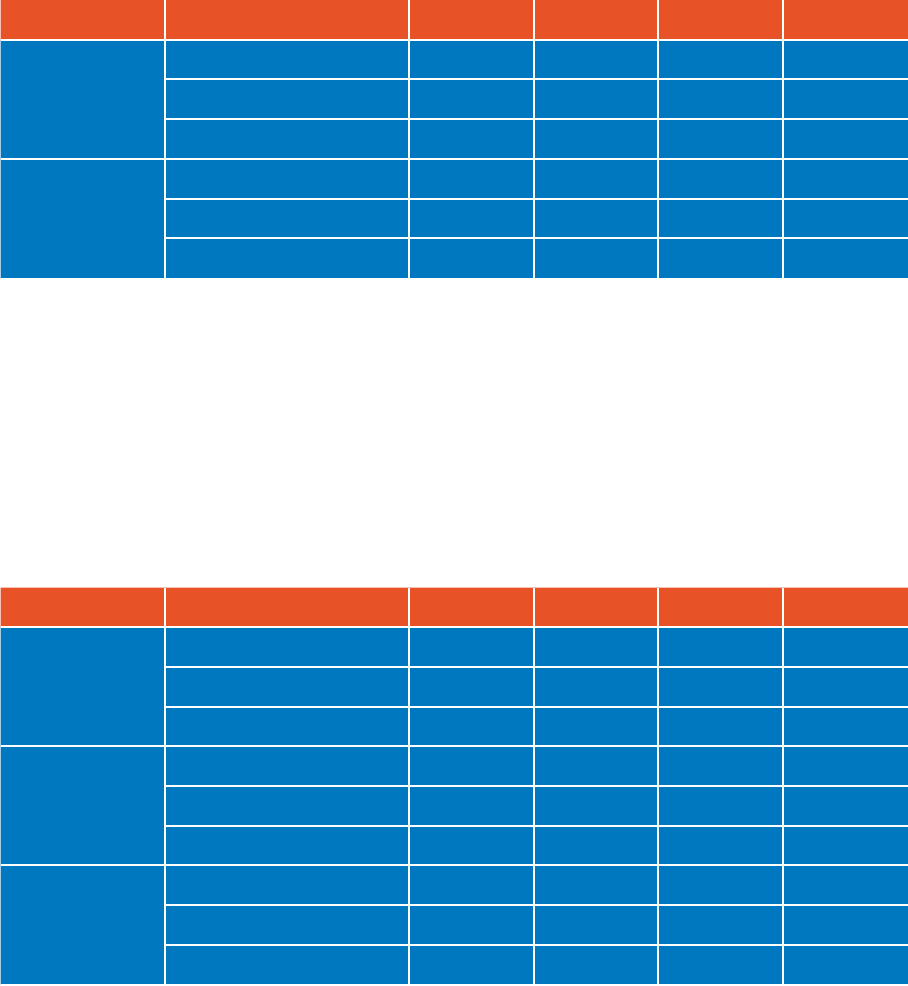

Tax relief impact, 2019

13

Animation Children’s

TV

HETV Film

2016 2017 2018

Tax relief impact, 2019

Animation Children’s

TV

HETV Film

2016 2017 2018

Animation Children’s

TV

HETV Film

2016 2017 2018

Animation Children’s

TV

HETV Film

2016 2017 2018

Return on tax relief (RoI)GVA Employment (FTEs) Tax revenue

* The video games methodology has

evolved since the 2018 edition of

Screen Business and also differs from

the approach used to calculate the

economic impact of FTR, HETR, ATR

and CTR. Therefore, the data are not

directly comparable and, as such, the

economic impact of video games is

presented separately.

£12.41bn

overall GVA

R

e

t

u

r

n

o

n

t

a

x

r

e

l

i

e

f

(

R

o

I

)

G

V

A

T

a

x

r

e

v

e

n

u

e

E

m

p

l

o

y

m

e

n

t

(

F

T

E

s

)

A

n

i

m

a

t

i

o

n

£

6

5

.

3

m

C

h

i

l

d

r

e

n

’

s

T

V

£

8

6

.

0

m

H

i

g

h

-

e

n

d

T

V

£

2

.

0

7

8

b

n

F

i

l

m

£

2

.

0

1

6

b

n

F

i

l

m

1

2

0

,

6

5

0

F

i

l

m

£

7

.

6

8

5

b

n

F

i

l

m

£

8

.

3

0

F

i

l

m

£

1

.

8

9

3

b

n

H

i

g

h

-

e

n

d

T

V

7

4

,

6

2

0

H

i

g

h

-

e

n

d

T

V

£

4

.

1

7

7

b

n

H

i

g

h

-

e

n

d

T

V

£

6

.

4

4

H

i

g

h

-

e

n

d

T

V

£

1

.

2

6

3

b

n

C

h

i

l

d

r

e

n

’

s

T

V

4

,

0

3

0

C

h

i

l

d

r

e

n

’

s

T

V

£

2

6

4

.

1

m

C

h

i

l

d

r

e

n

’

s

T

V

£

3

.

2

0

C

h

i

l

d

r

e

n

’

s

T

V

£

8

4

.

0

m

A

n

i

m

a

t

i

o

n

£

4

.

5

3

A

n

i

m

a

t

i

o

n

£

1

1

0

.

2

m

A

n

i

m

a

t

i

o

n

4

,

3

6

0

A

n

i

m

a

t

i

o

n

£

2

8

5

.

2

m

Production Expenditure*

£4.245bn

Tot al production

investment

Including video games tax relief,

overall GVA is £13.48 billion

% growth since 2017

+17.6%

*

Including video games

total production and

video games

investment is £5.11bn

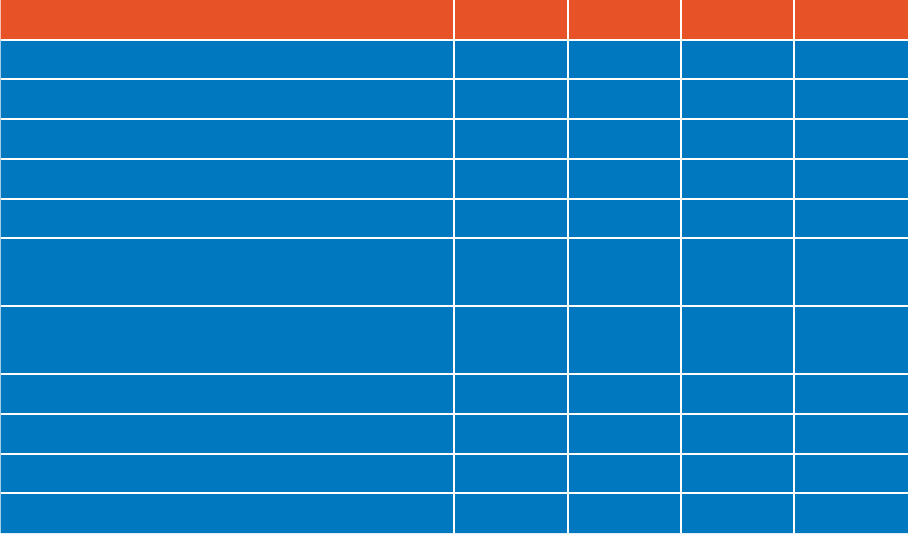

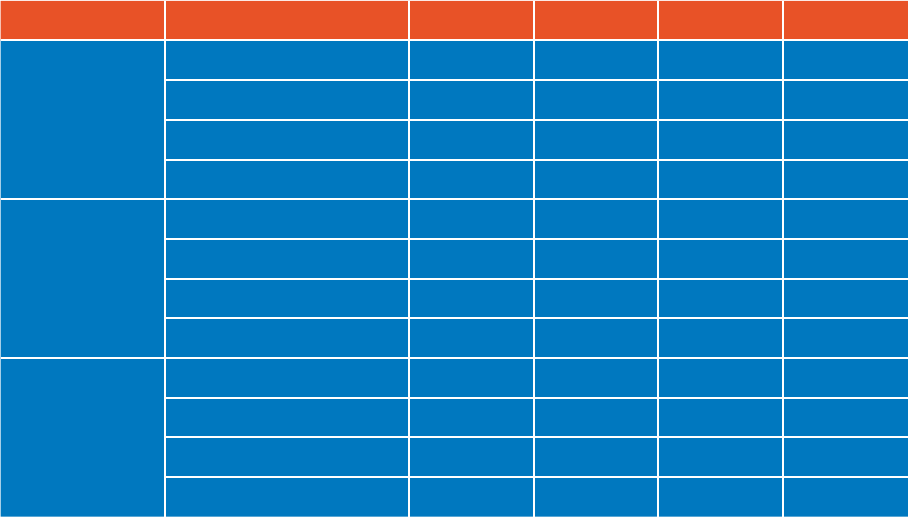

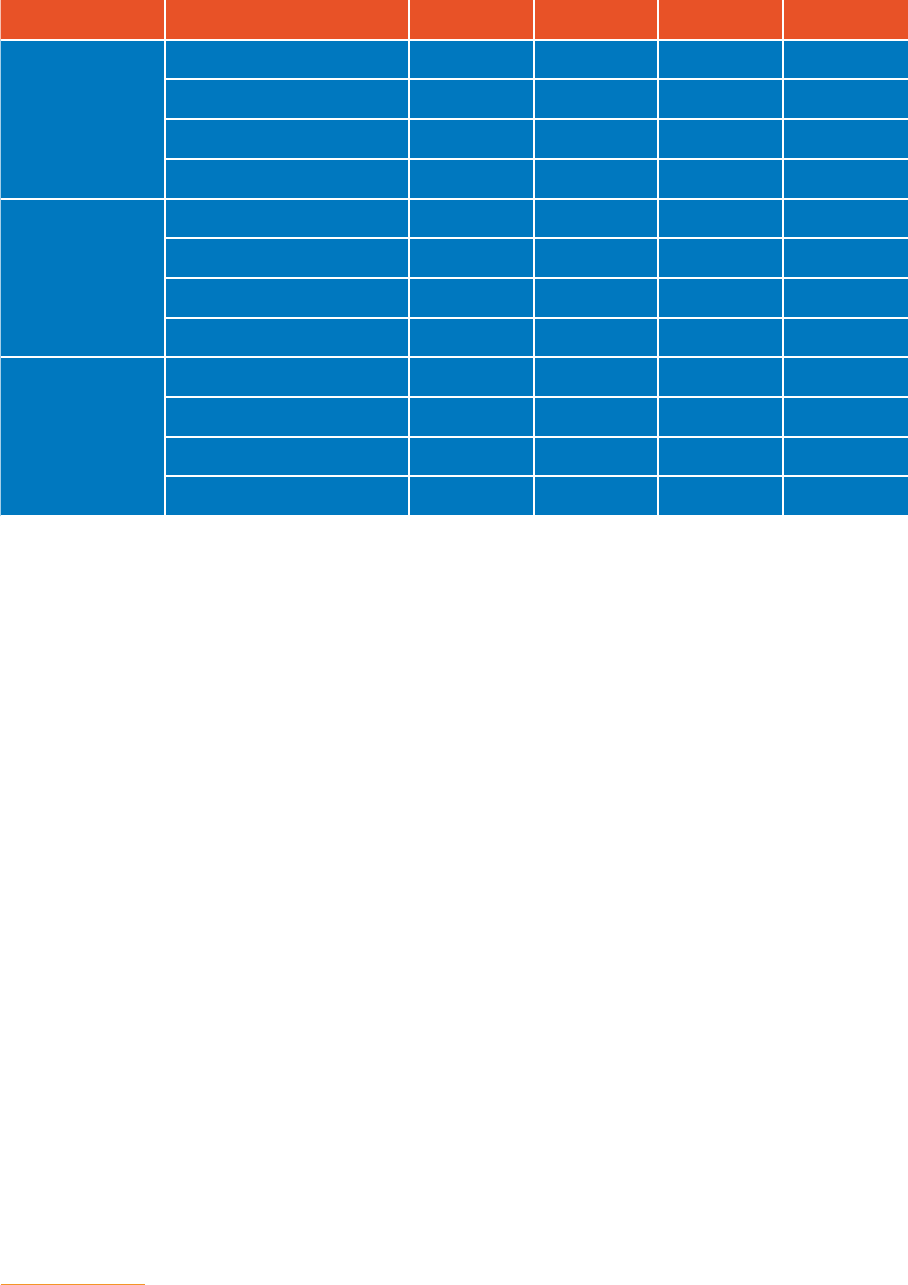

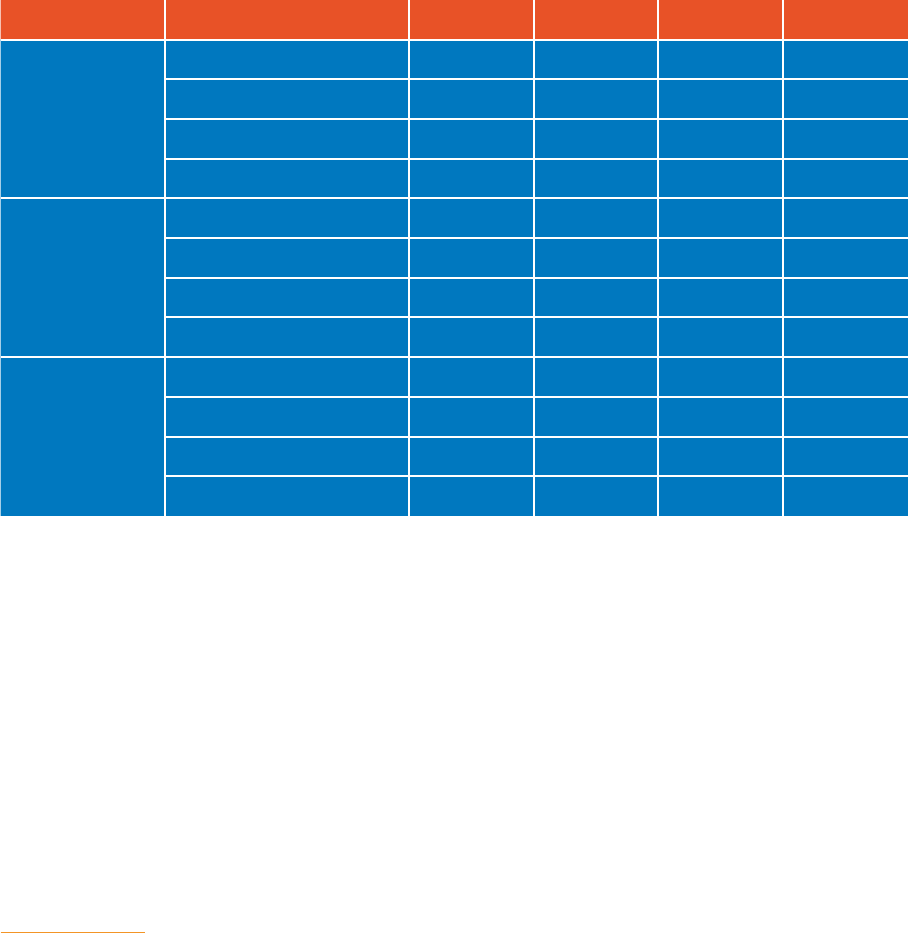

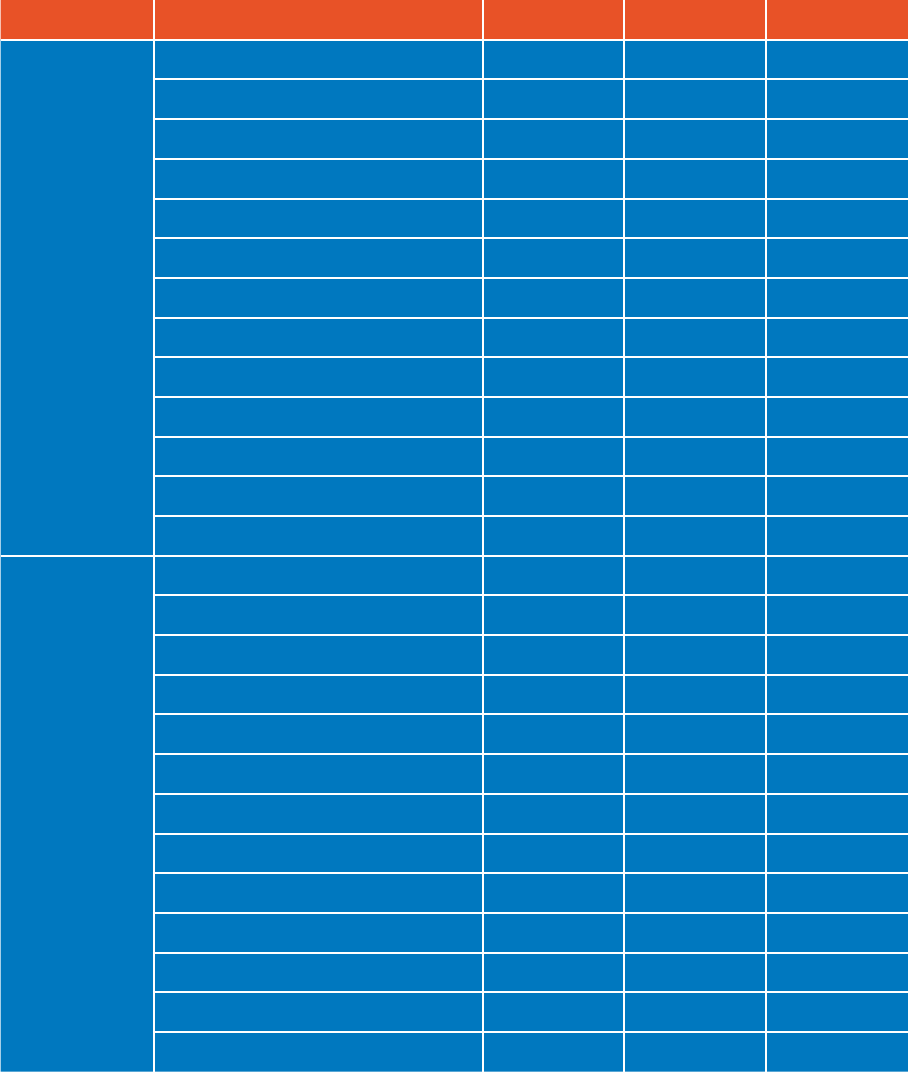

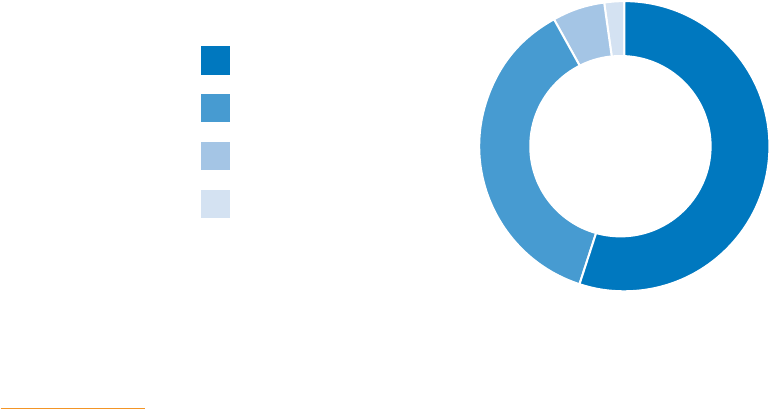

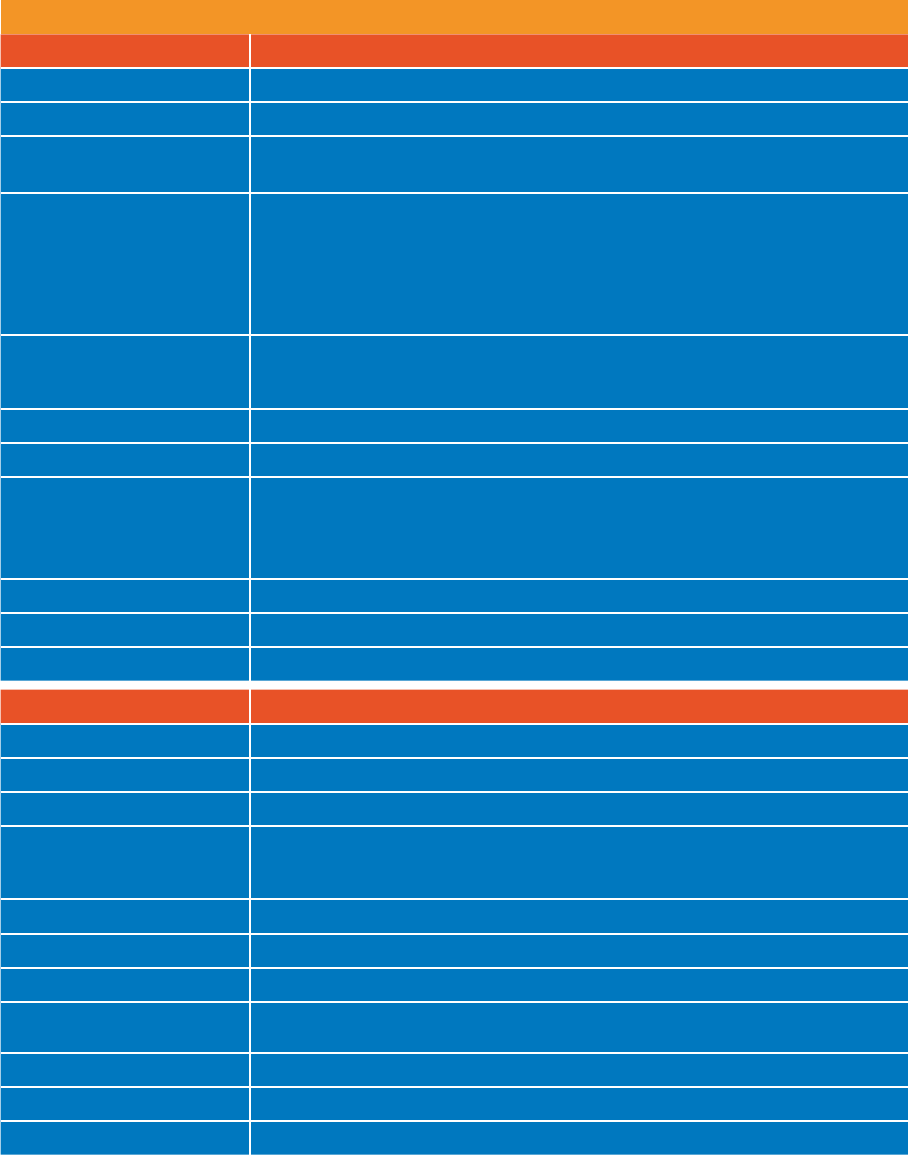

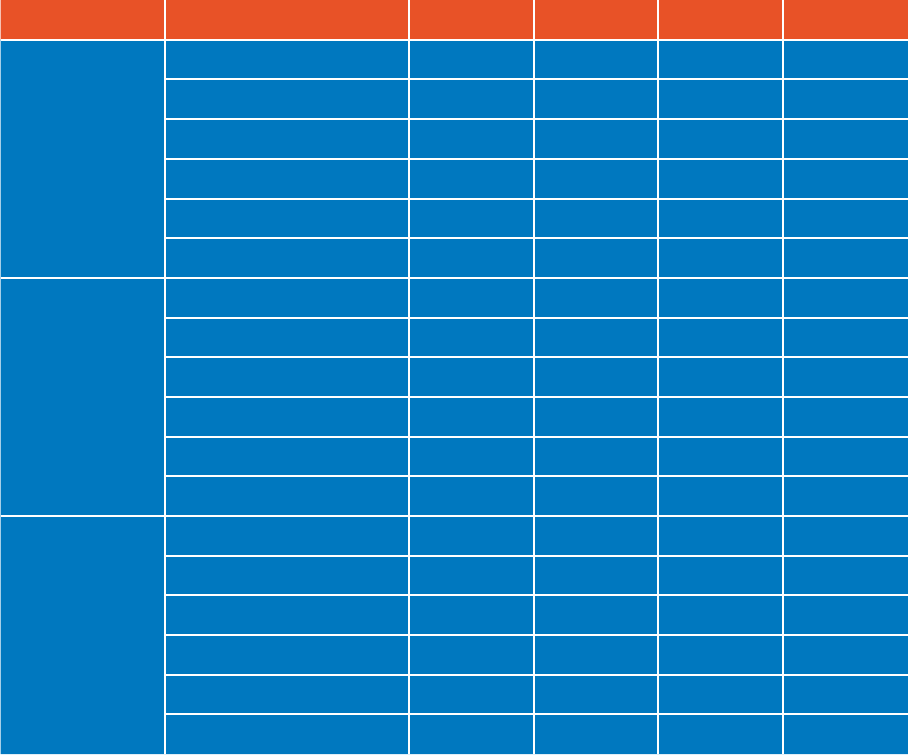

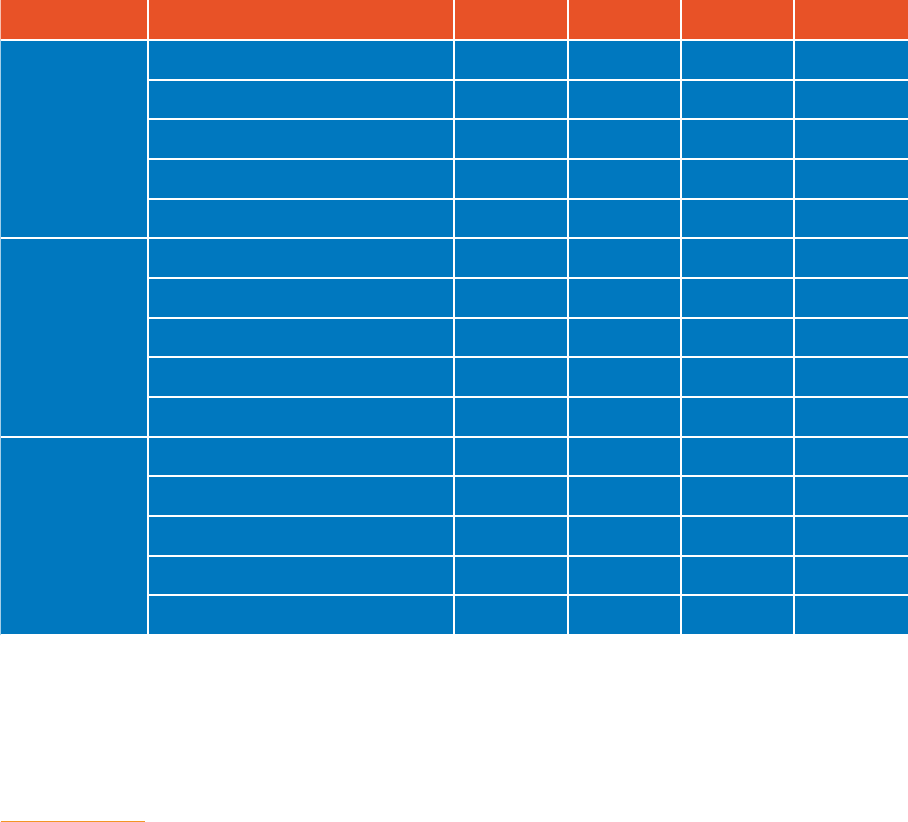

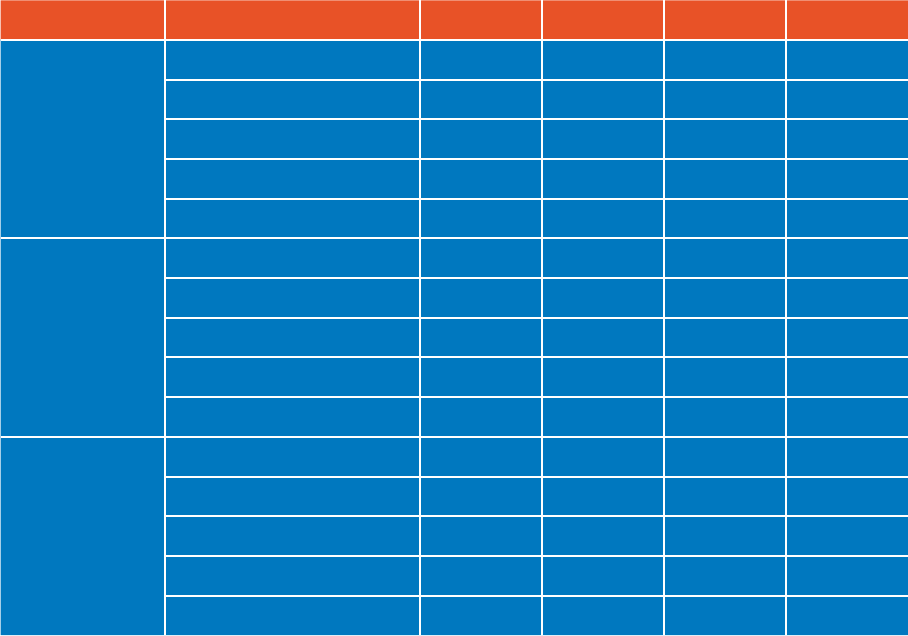

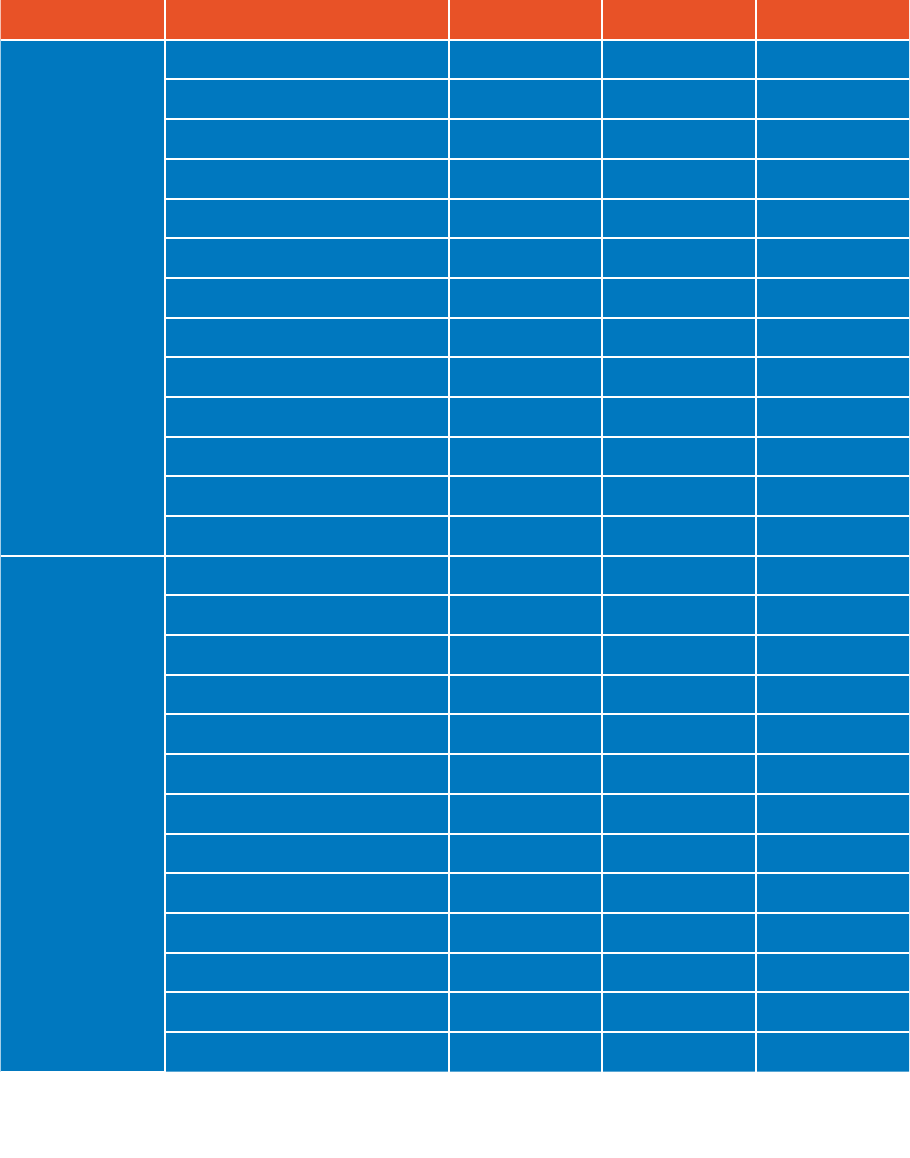

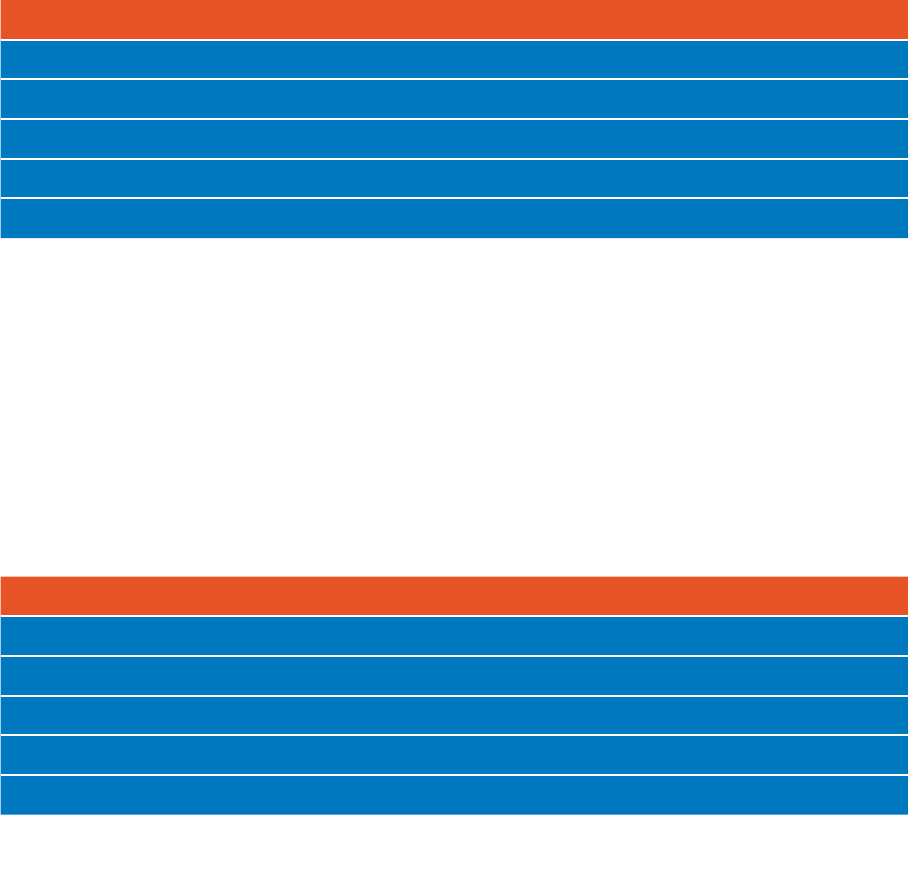

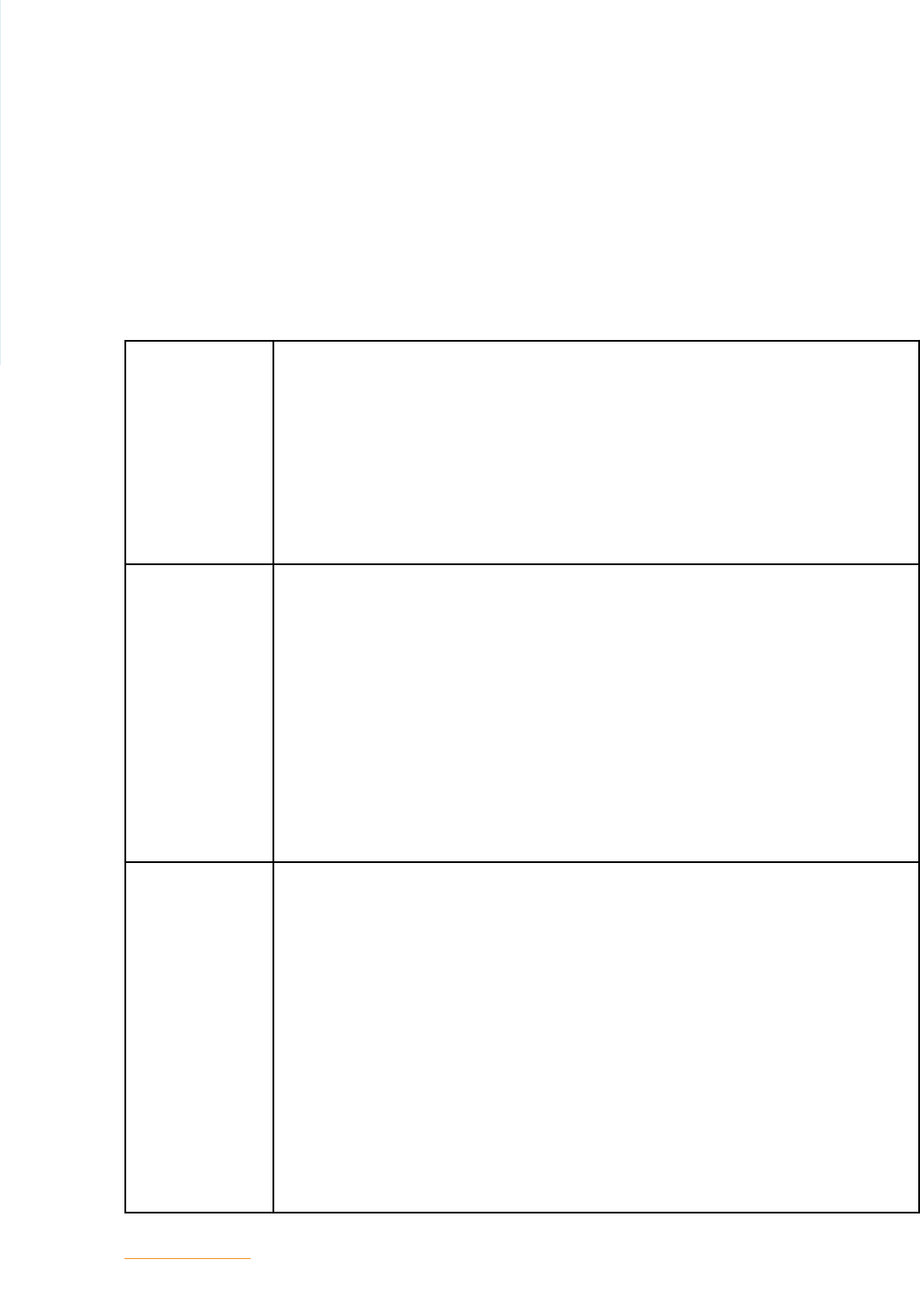

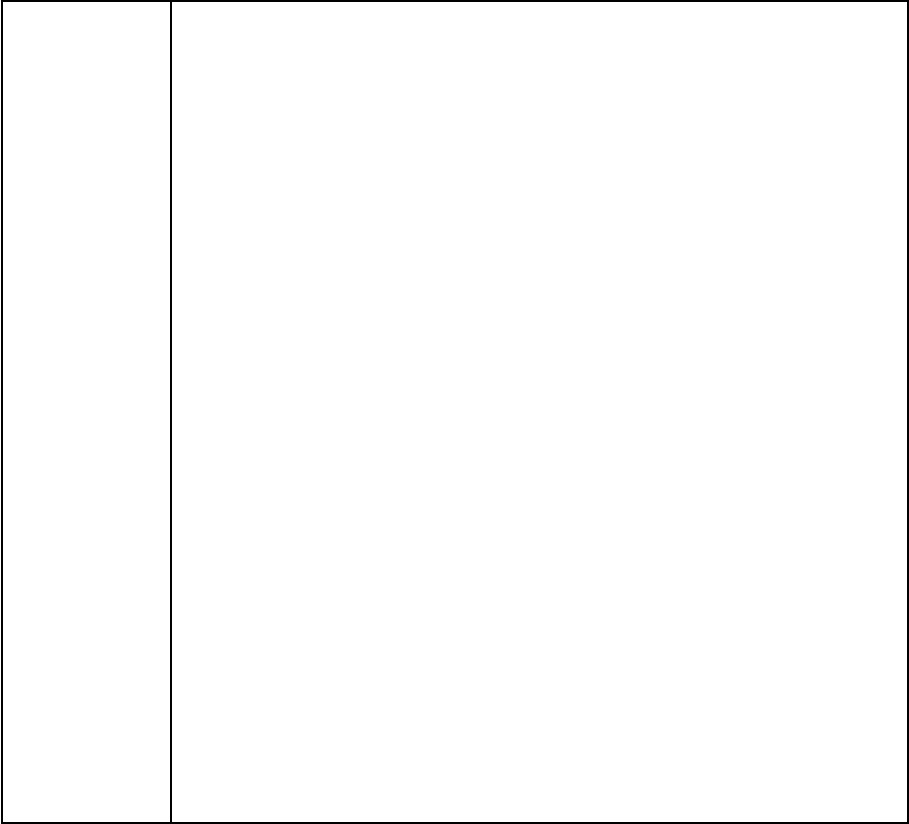

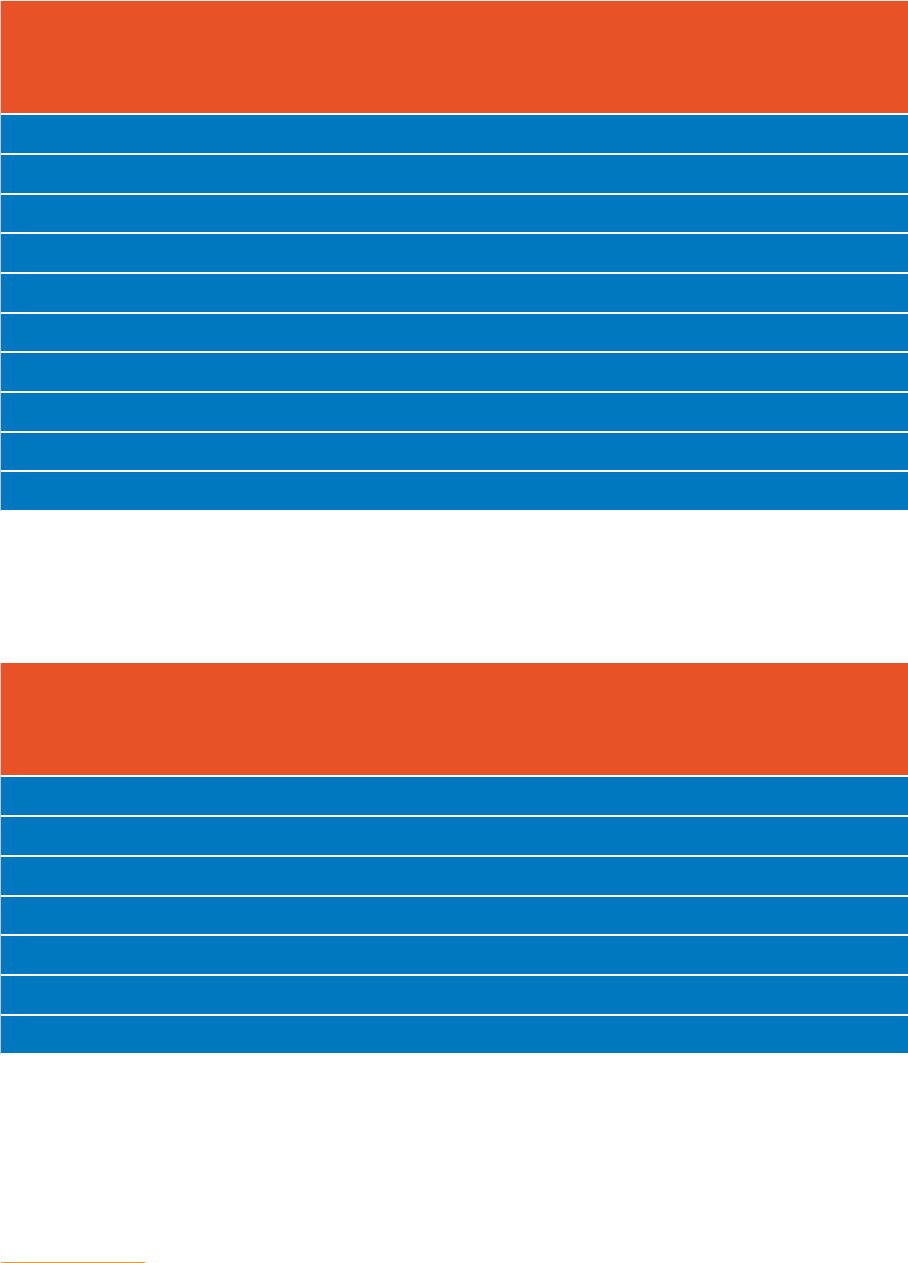

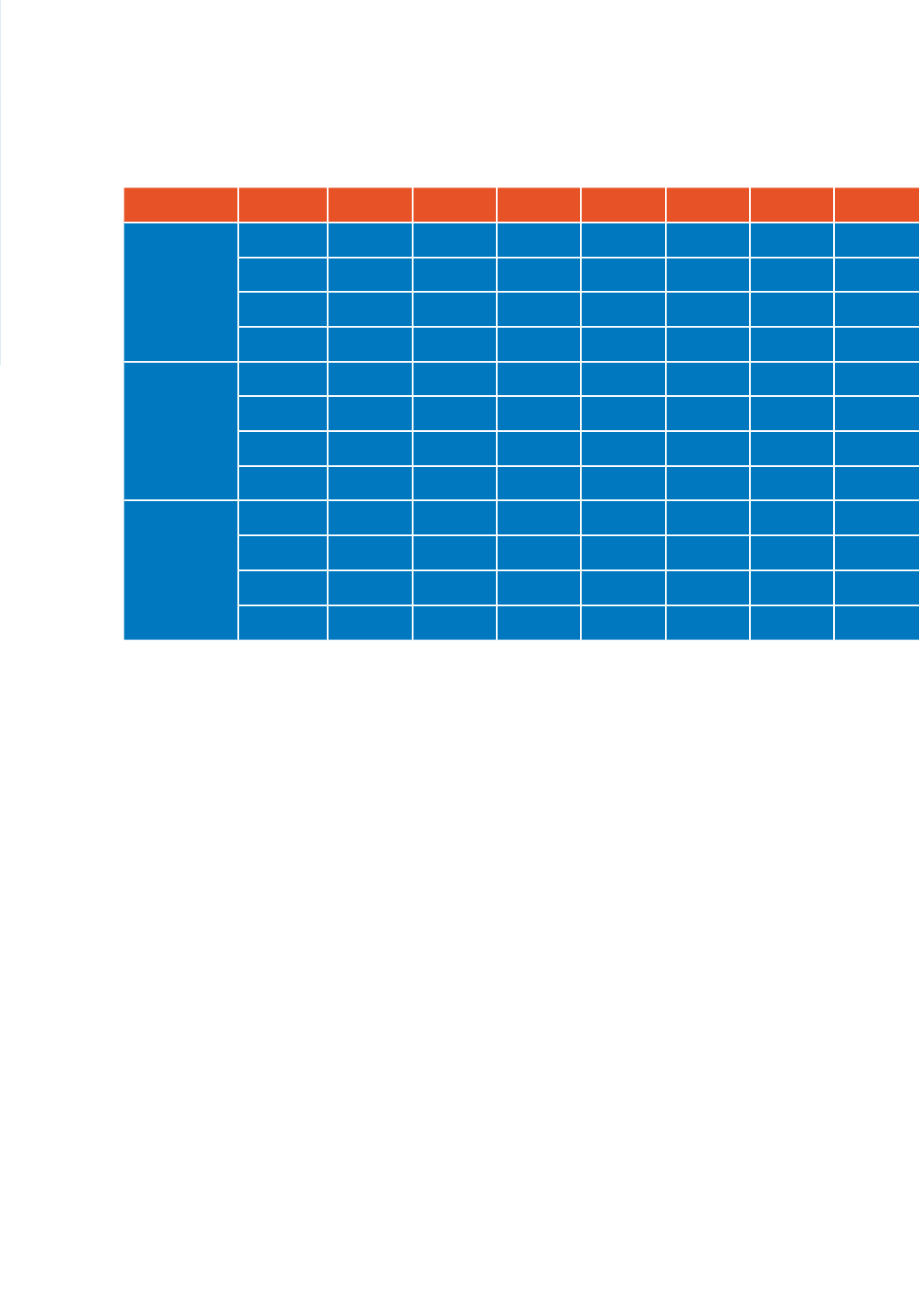

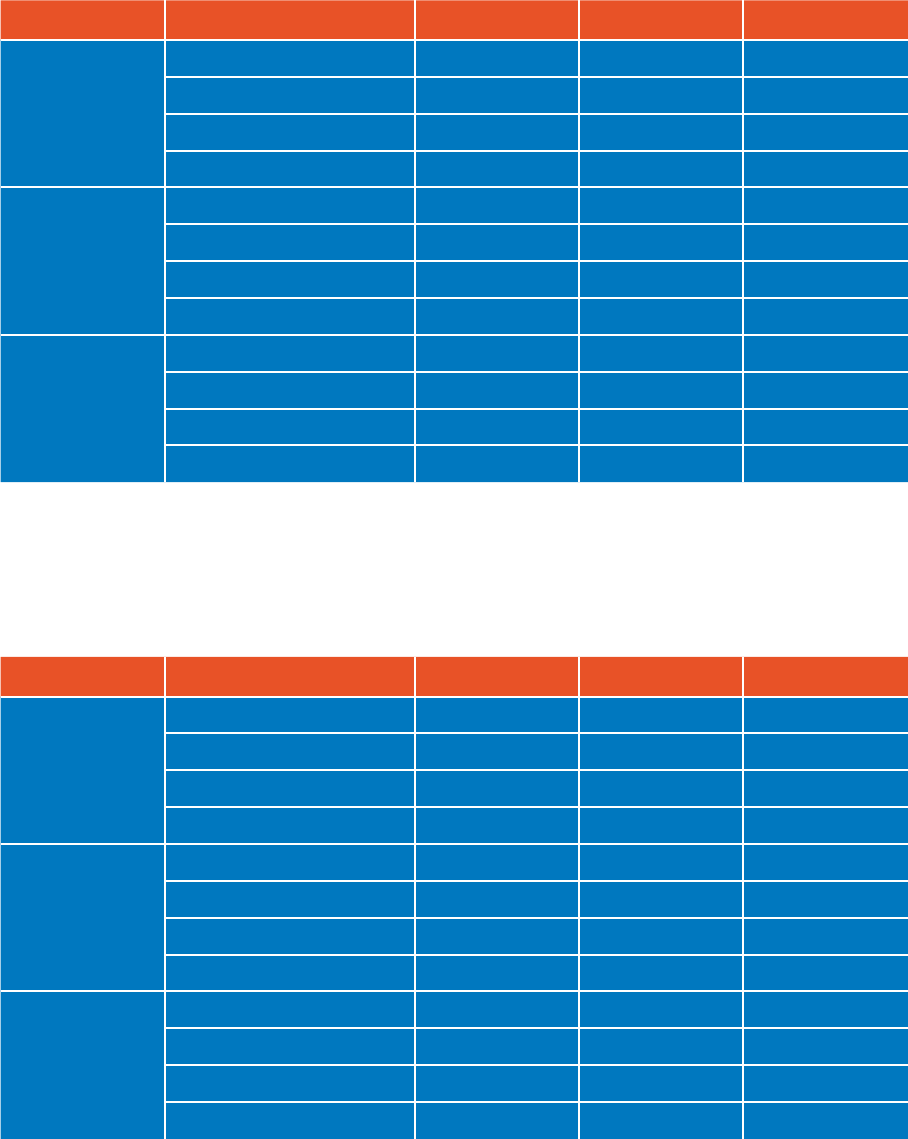

Video games impact, 2019*

14

Return on tax

relief (RoI)

Employment (FTEs):

15,030

Video Games Tax Relief impact, 2019 *

£860.4m

22.8%

growth 2017-2019

* The video games methodology has evolved since the 2018 edition of Screen

Business and also differs from the approach used to calculate the economic impact

of FTR, HETR, ATR and CTR. Therefore, the data are not directly comparable and,

as such, the economic impact of video games is presented separately.

Due to the length of the video games development process and the way in which

the Video Games Tax Relief (VGTR) supports developers, there can be a significant

lag in reporting and it can take several years for actual expenditure figures to

consolidate. Therefore, the profile of video games expenditure supported by the

tax relief in any given year is only a partial picture of the actual expenditure across

the sector.

The VGTR-supported video games sector in the UK represents only a portion of

current activity. To provide a full picture of the impact of the video games sector in

the UK, analysis has been undertaken for Screen Business to estimate the total

economic contribution of video games.

Spend in the UK

supported by the Video

Games Tax Relief is

Employment (FTEs) generated by all

video games developed, published

and sold in the UK: 71,400

GVA generated

by all video games

developed, published

and sold in the UK:

Total video games sector impact, 2019

£2.77bn

Total UK

spend/turnover

relating to direct

impact of video games

development in the UK

Tax revenue

£246.3m

£1.06bn

GVA

£5.12bn

£1.72

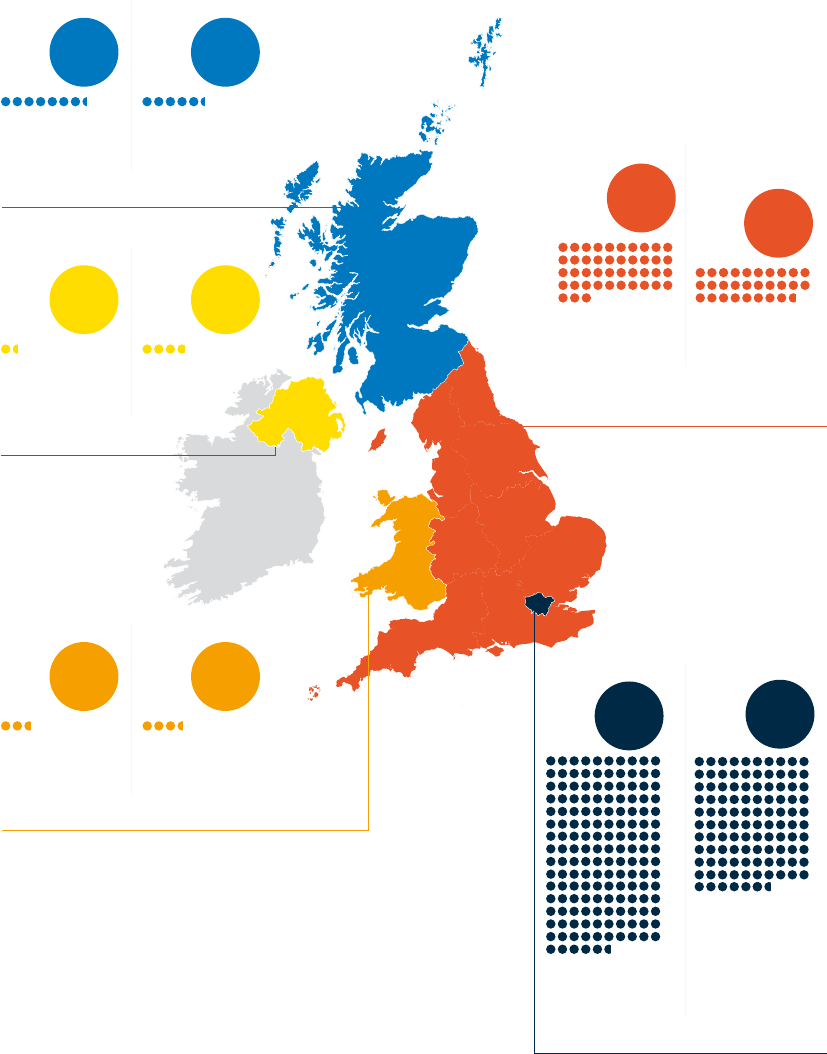

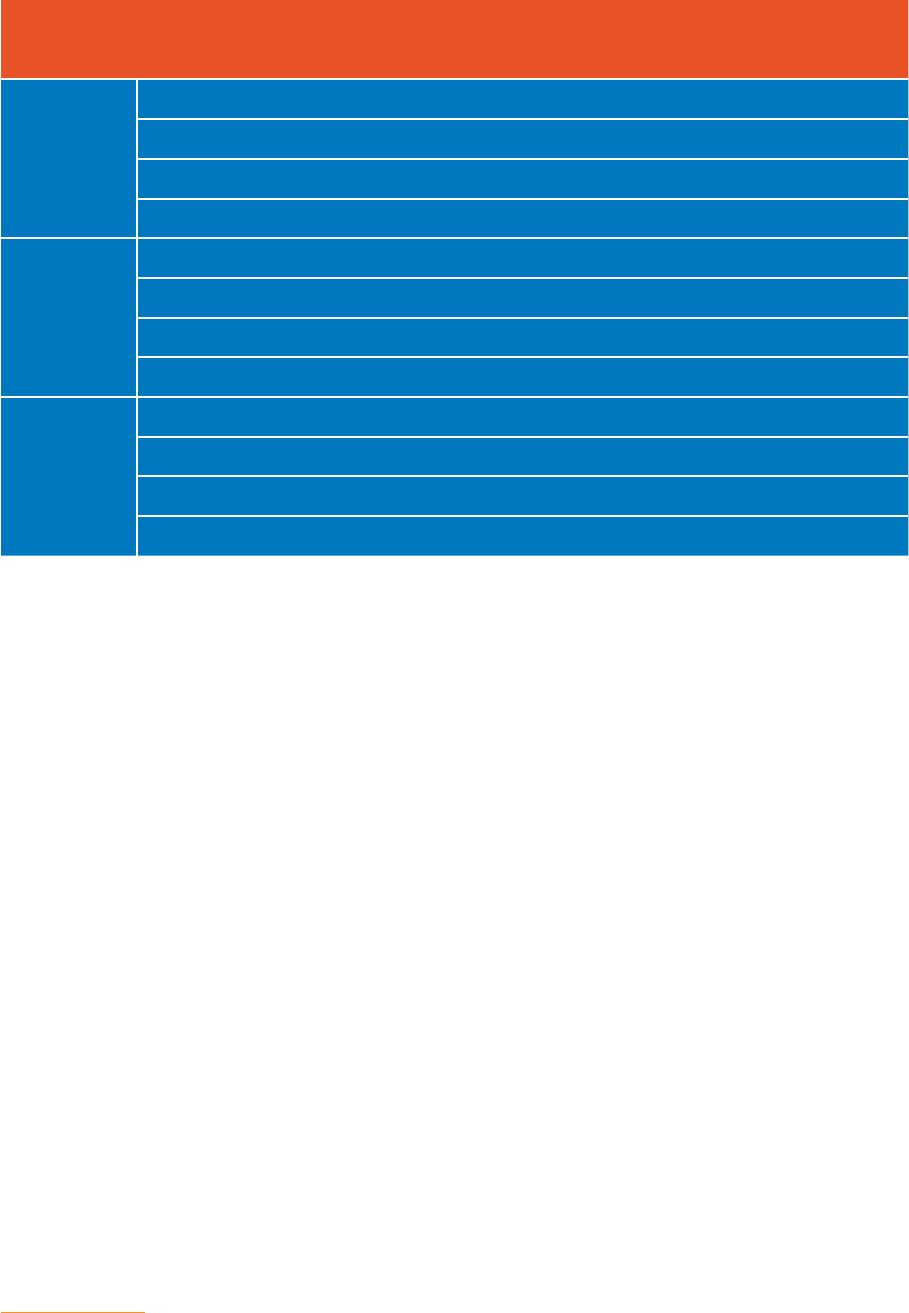

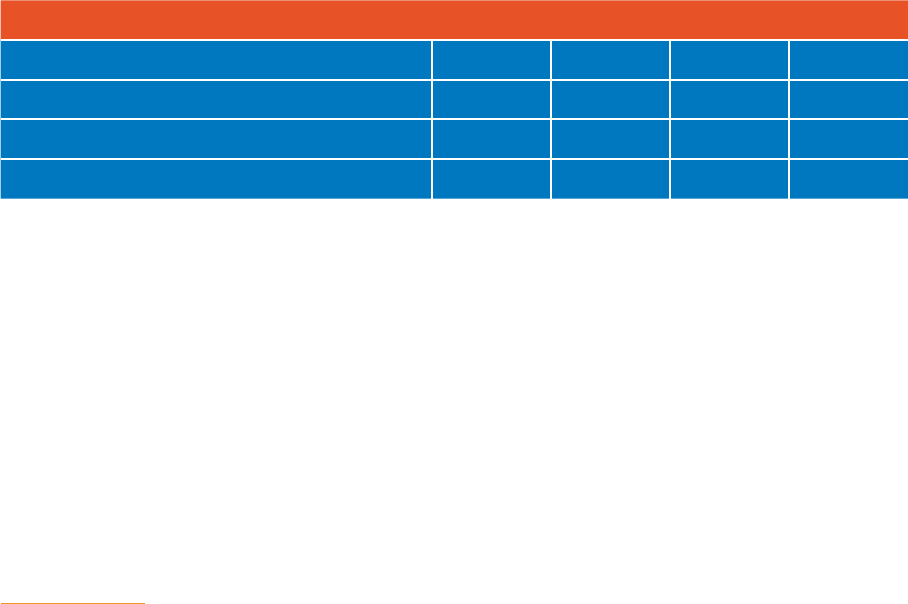

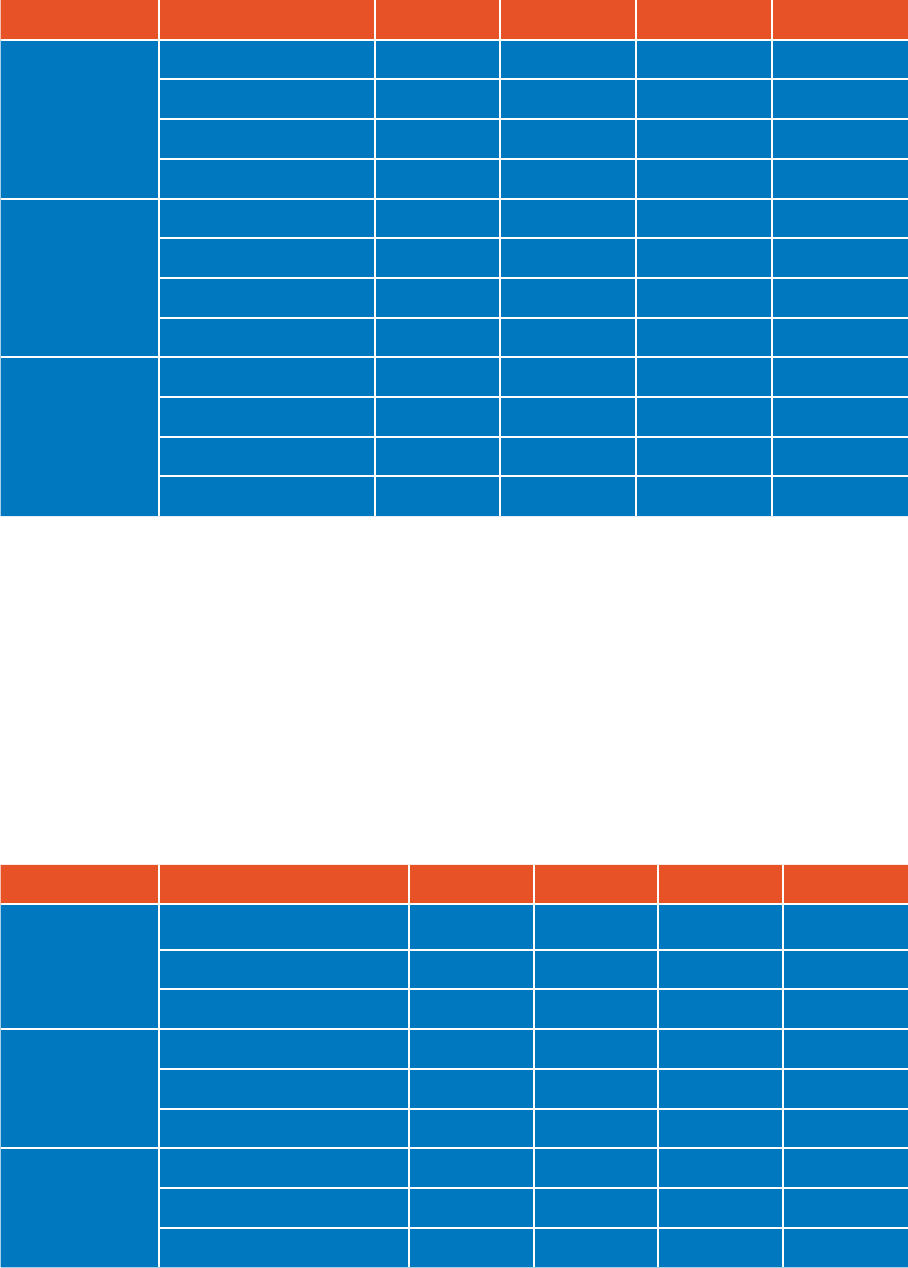

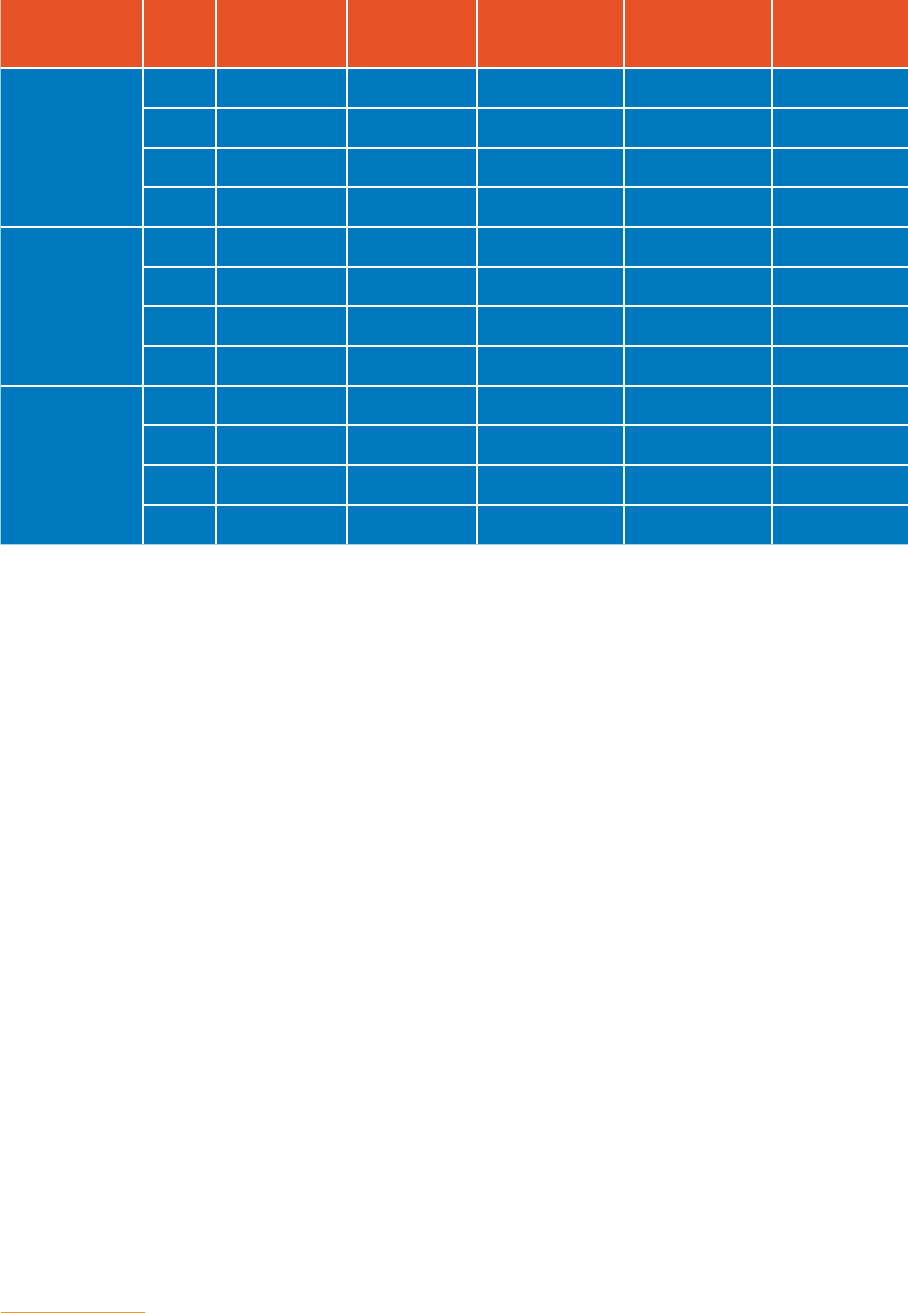

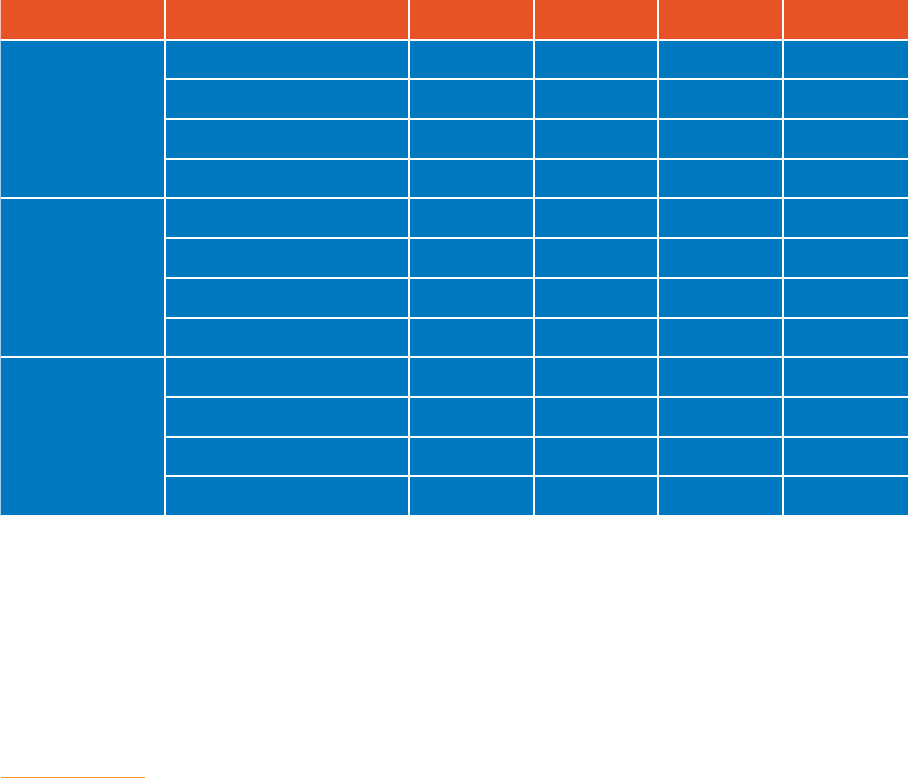

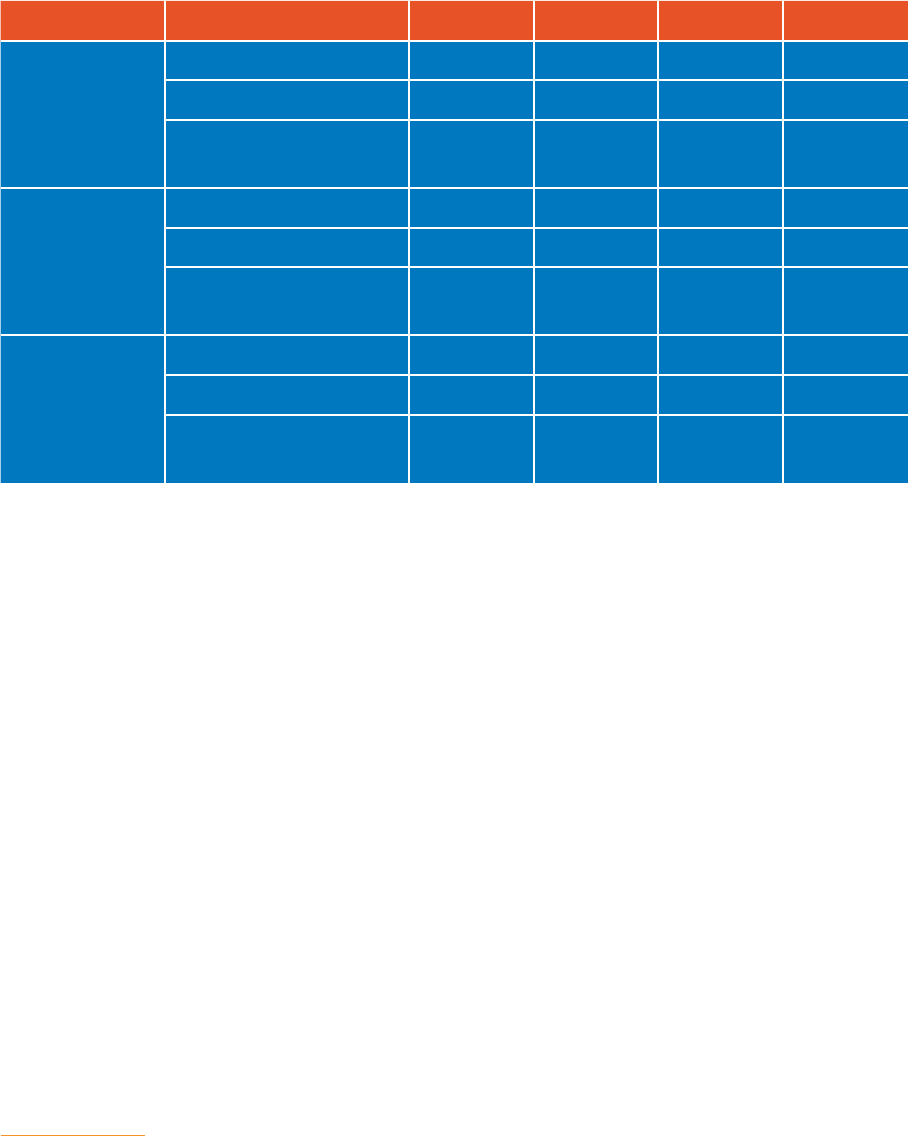

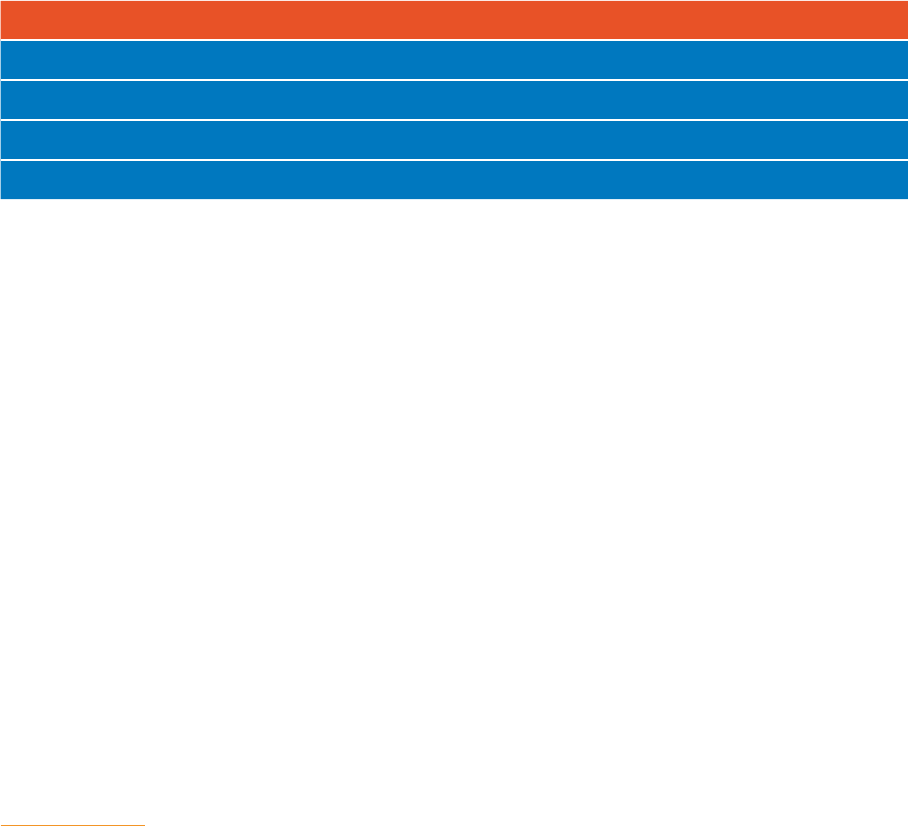

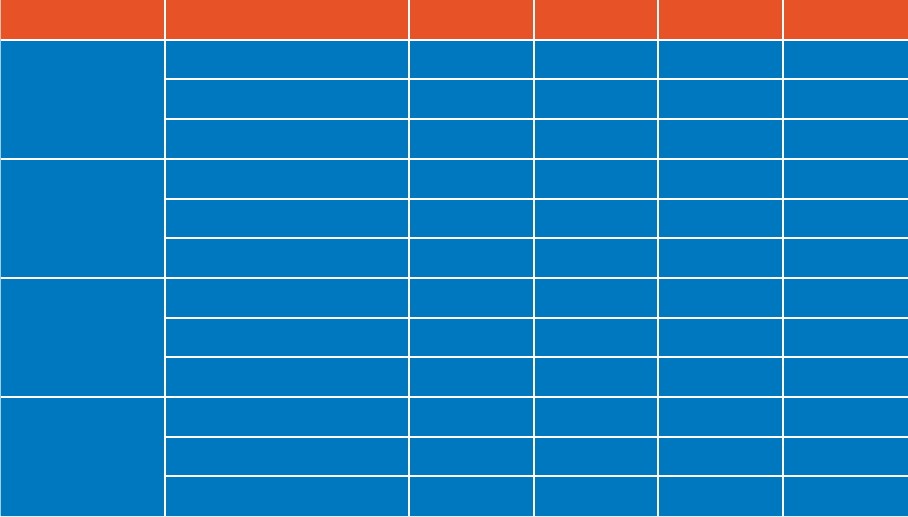

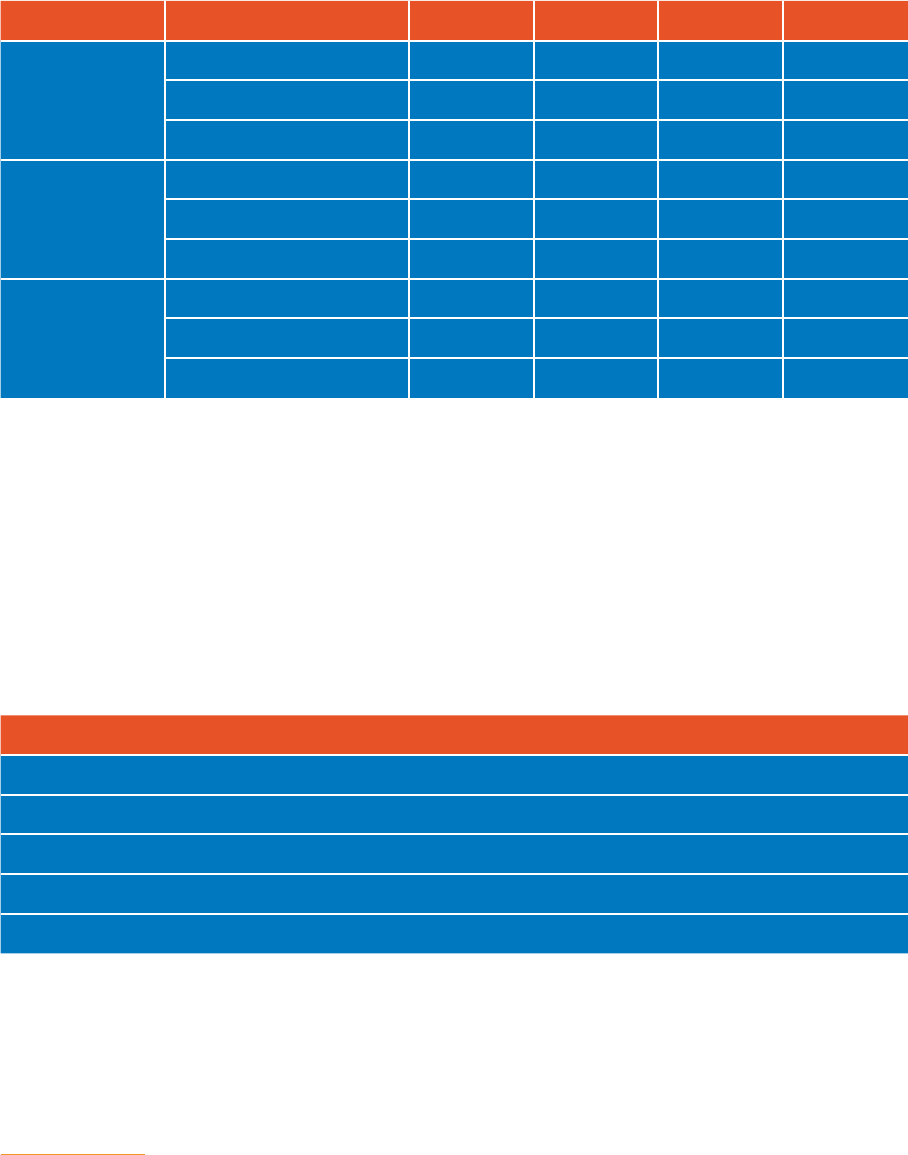

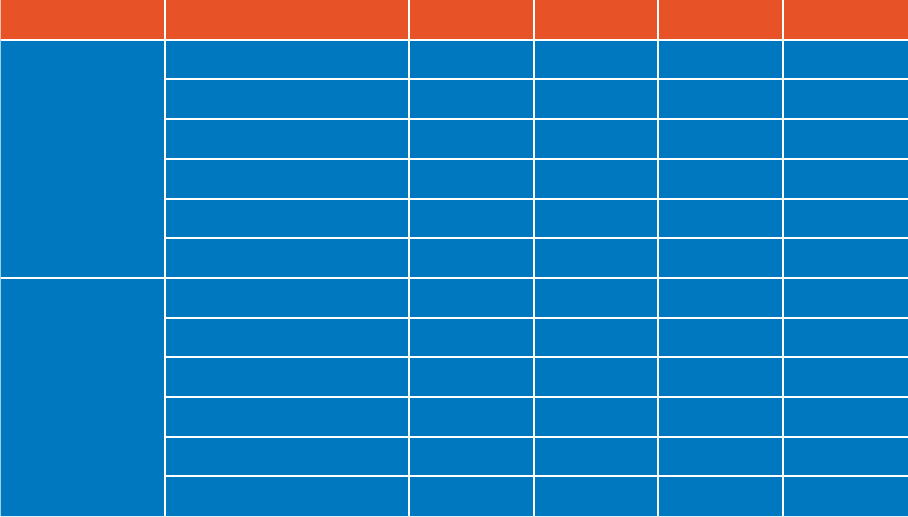

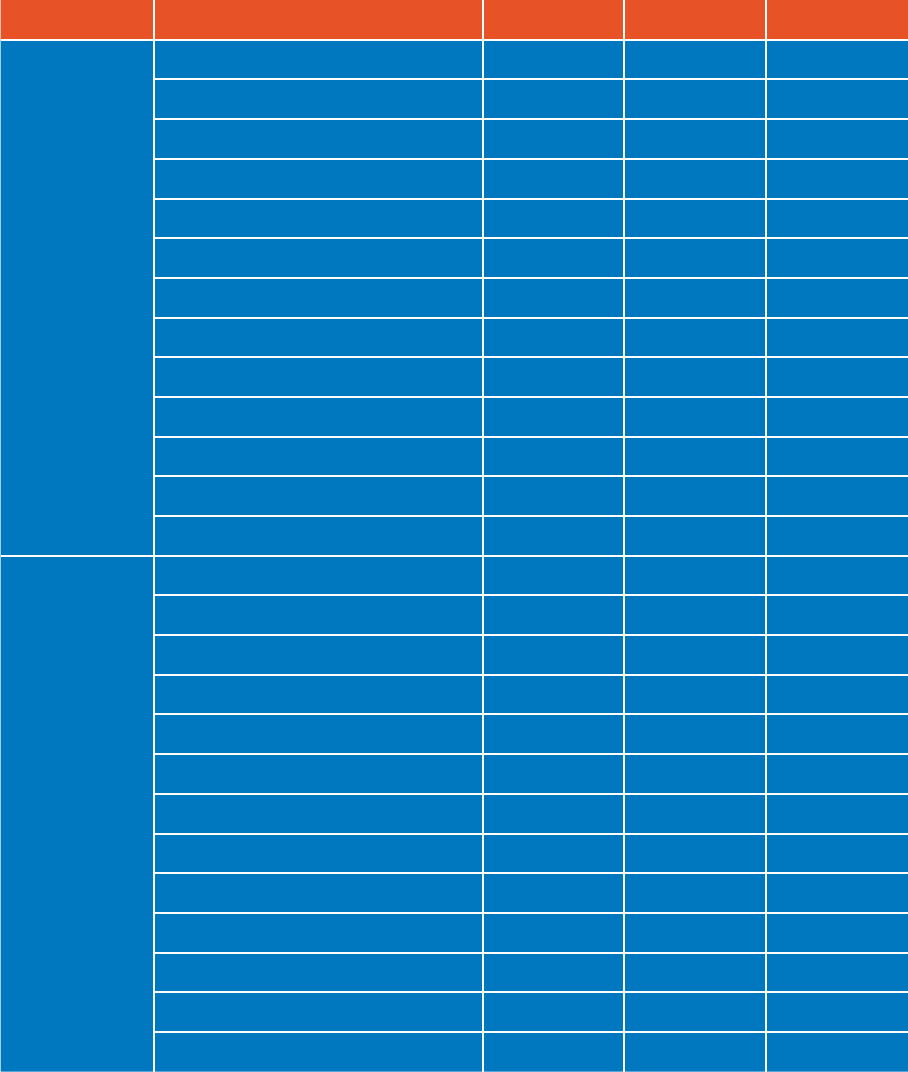

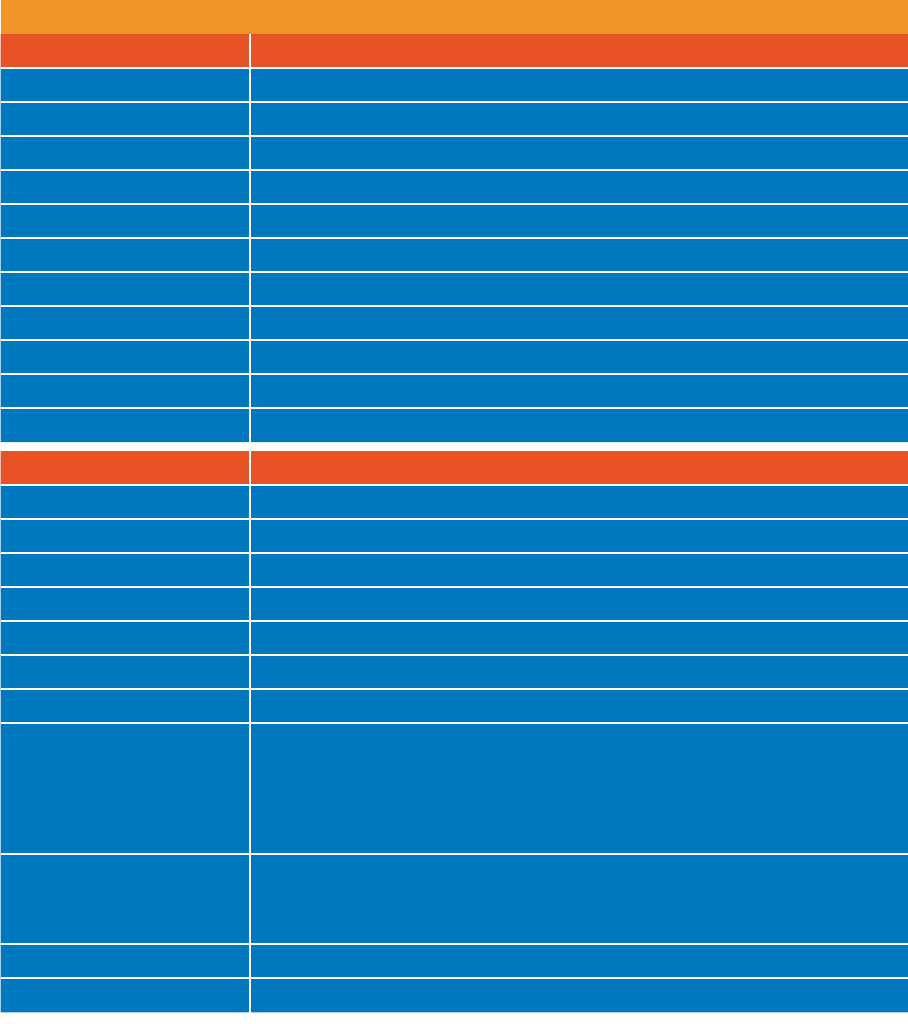

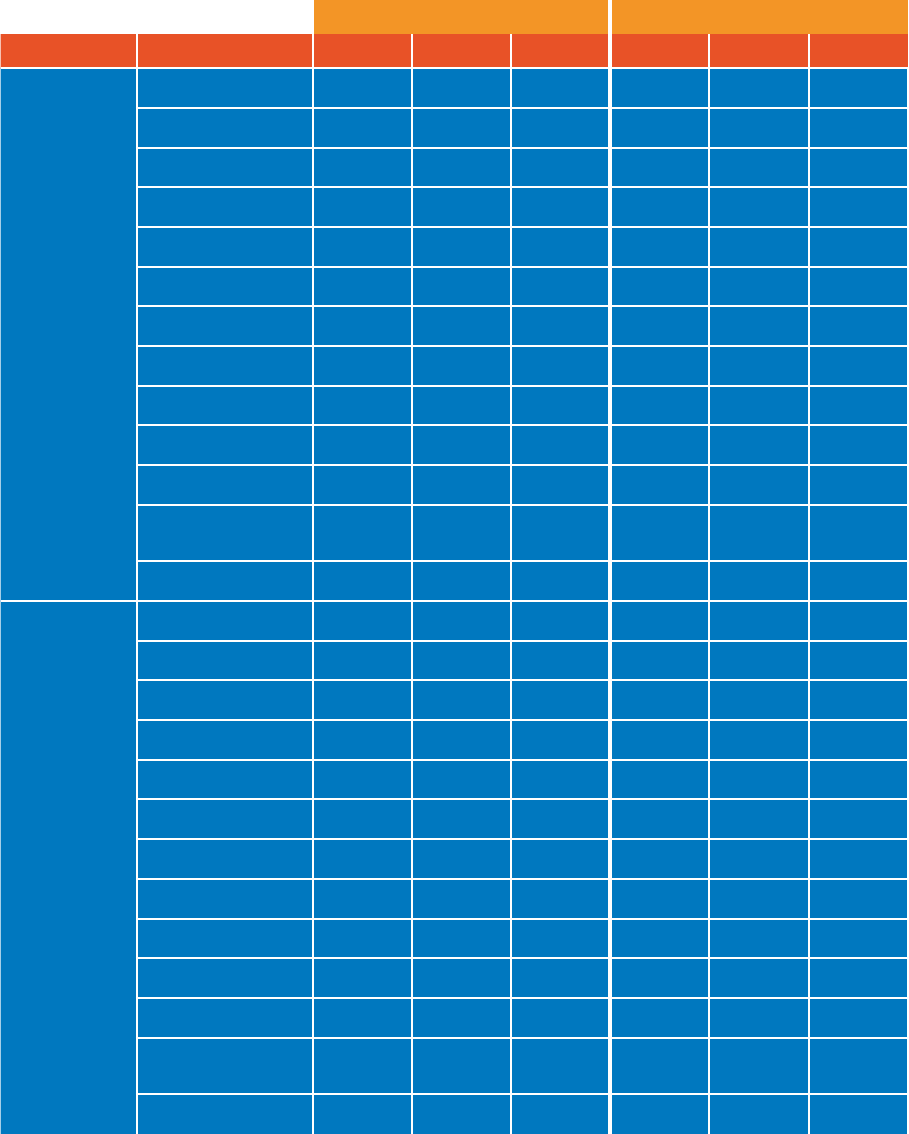

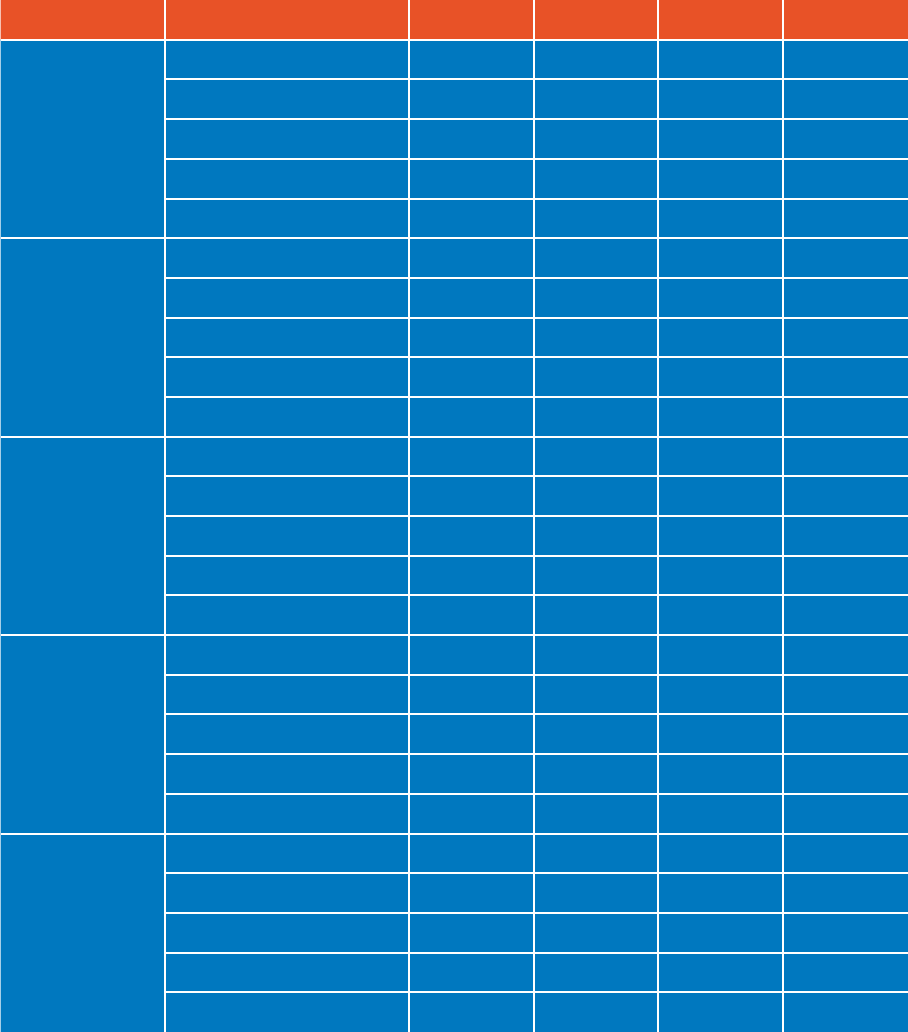

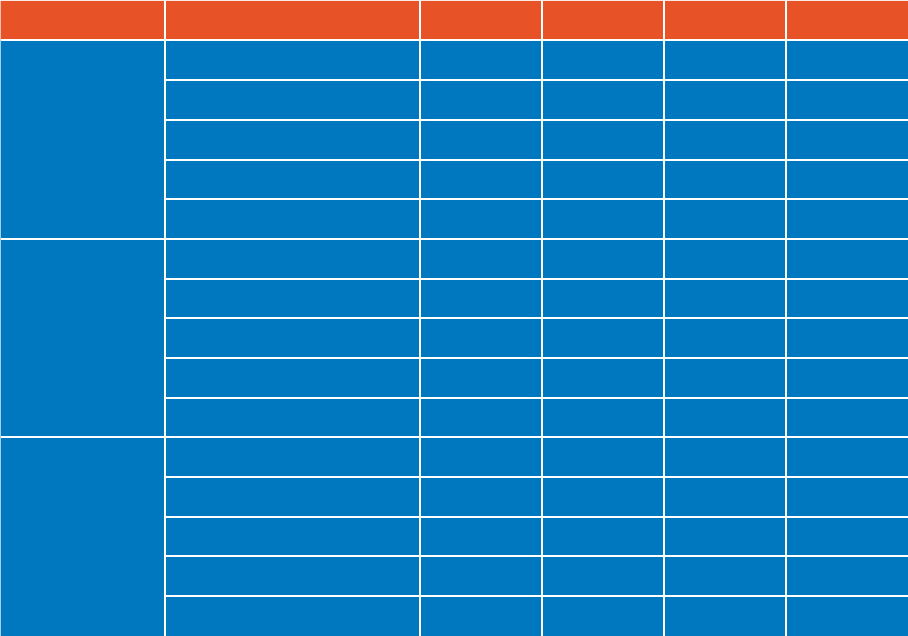

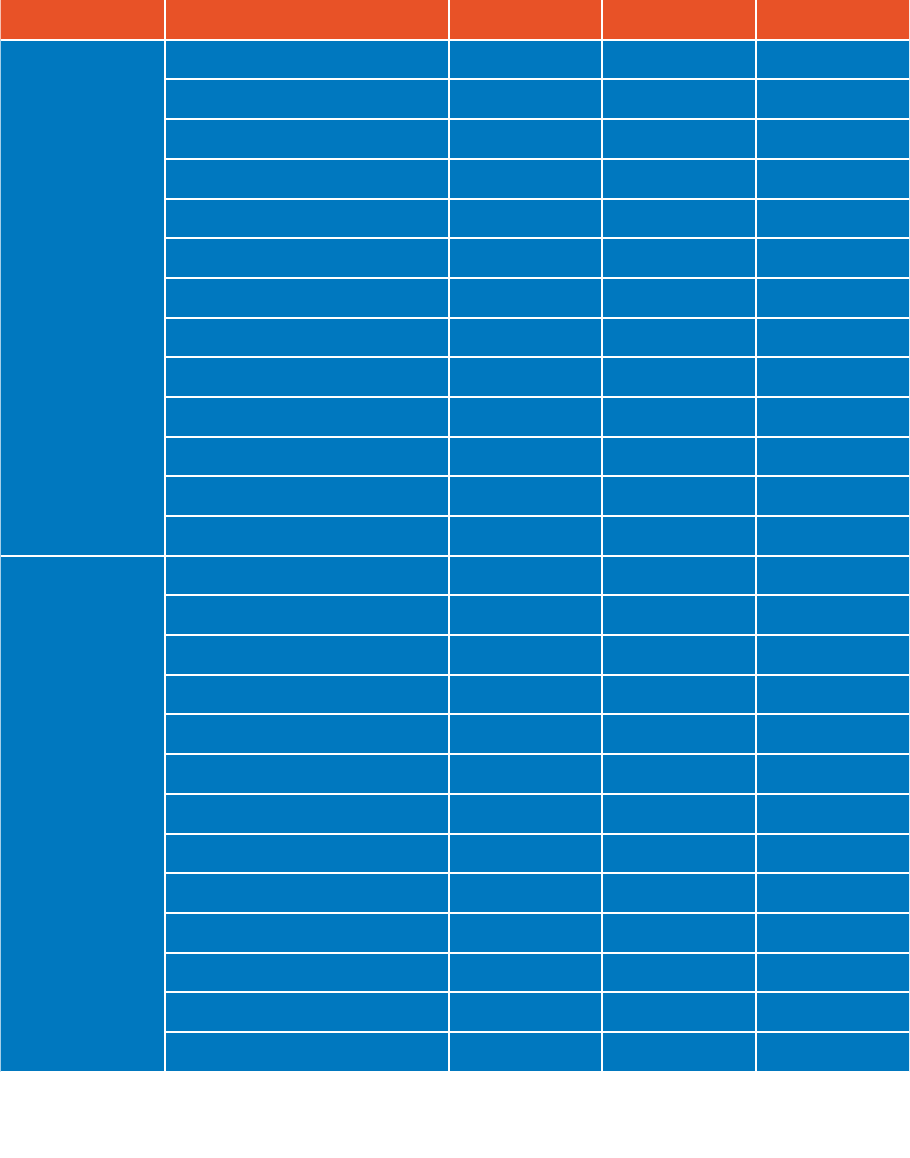

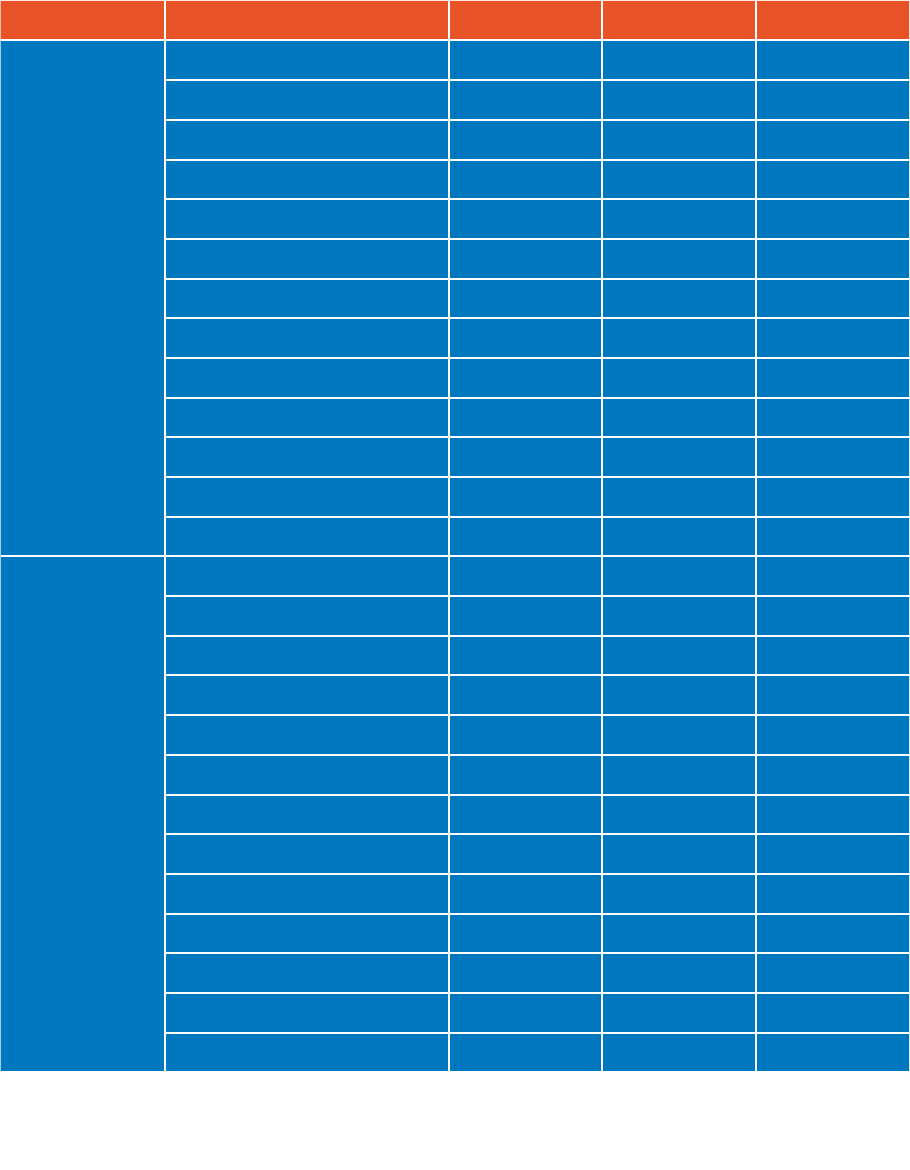

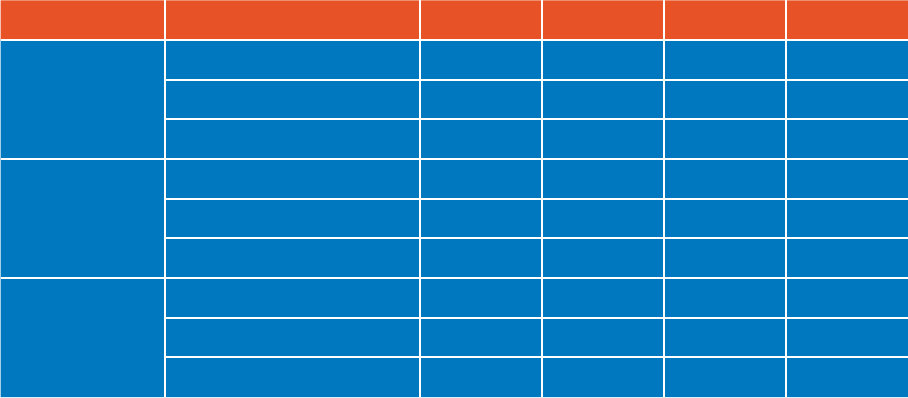

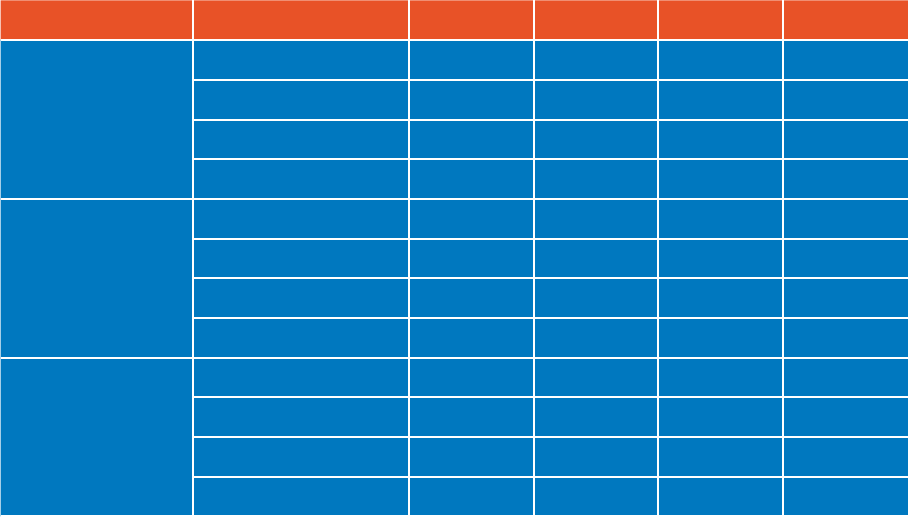

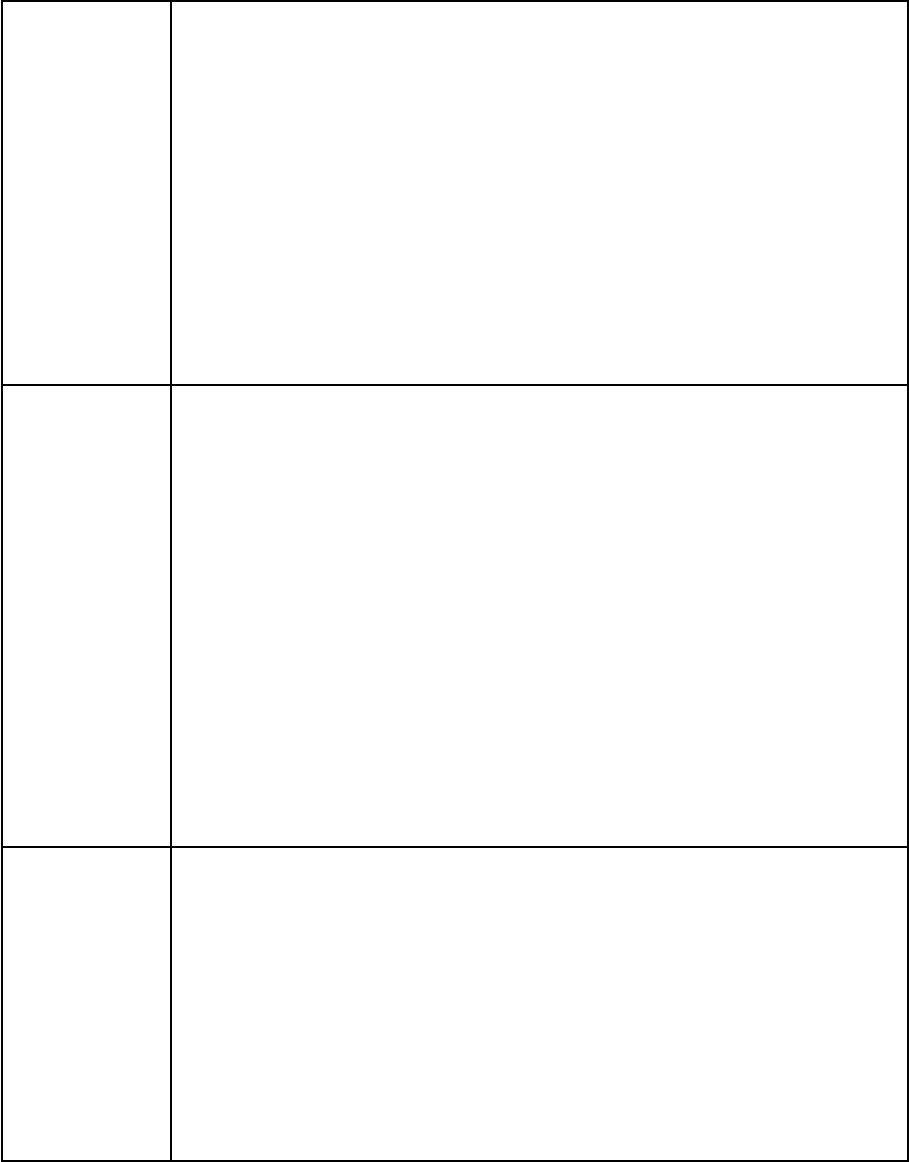

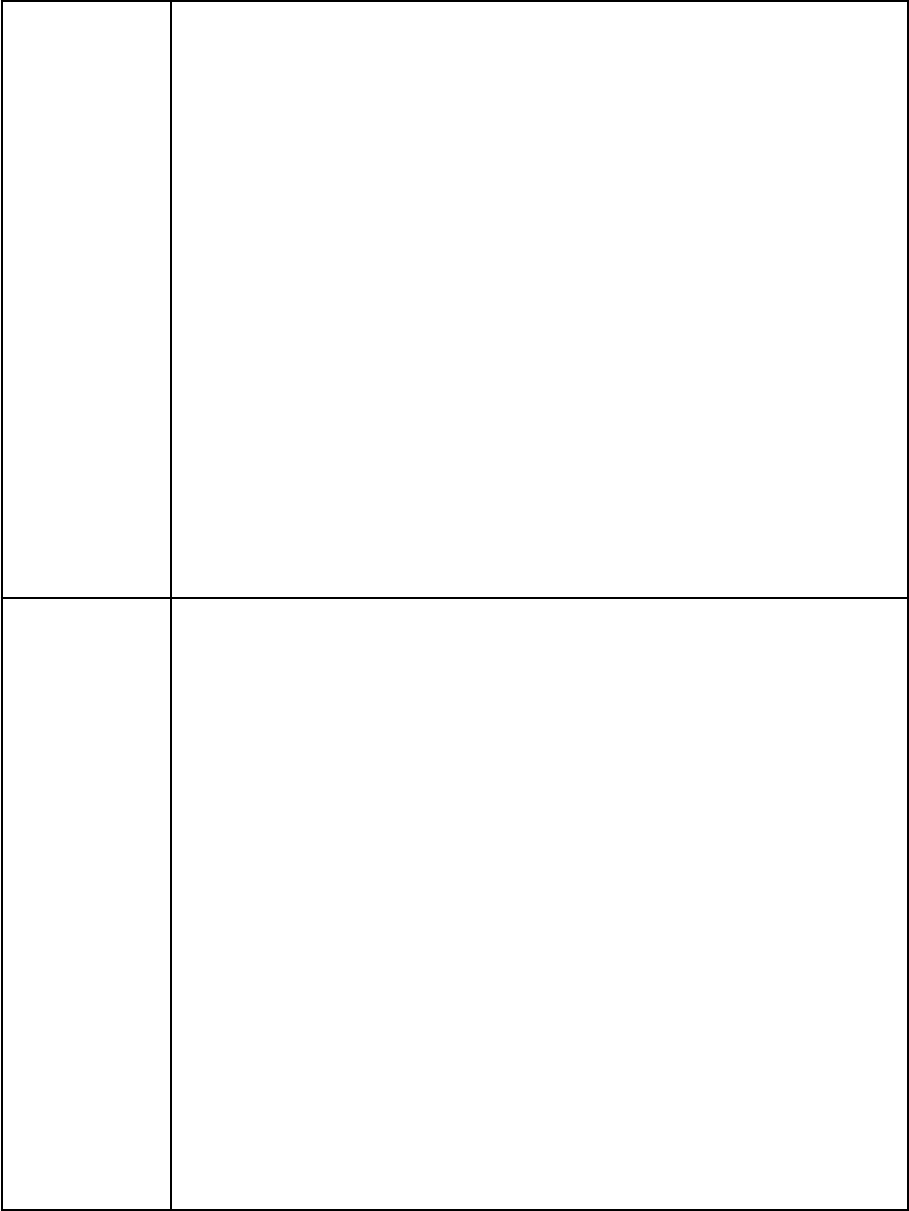

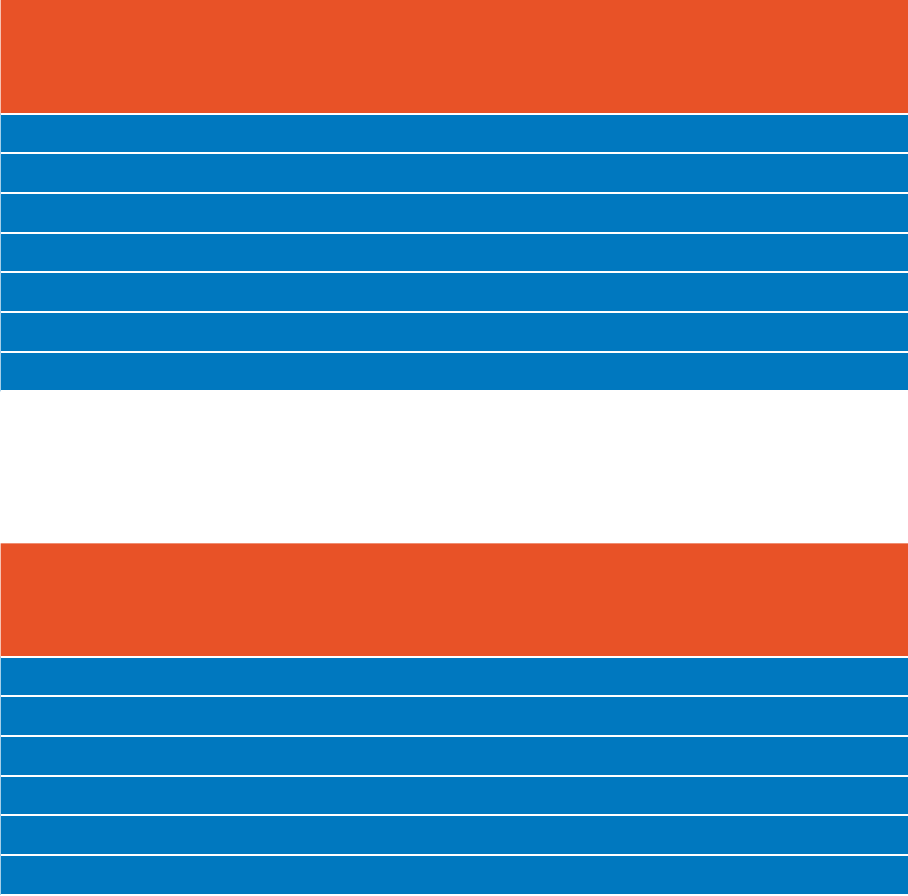

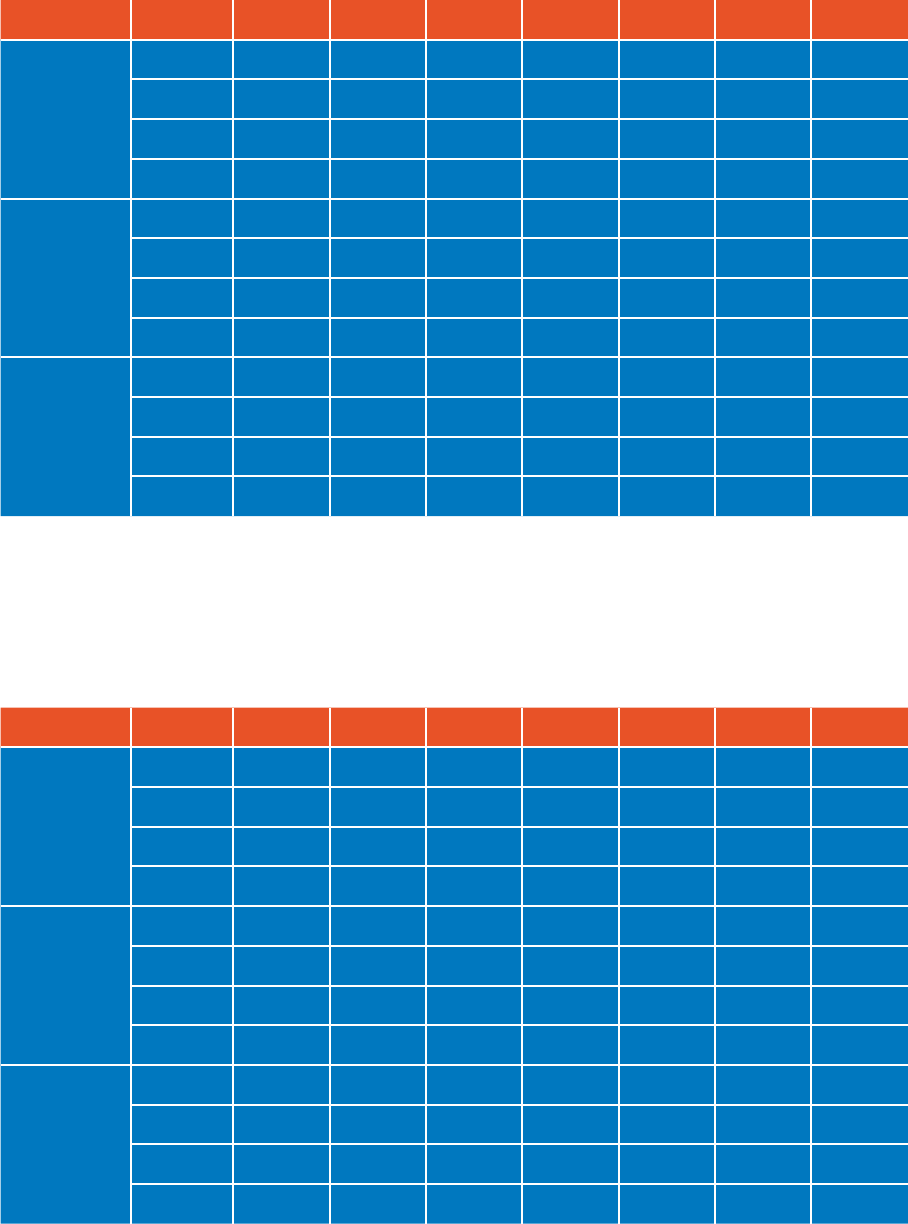

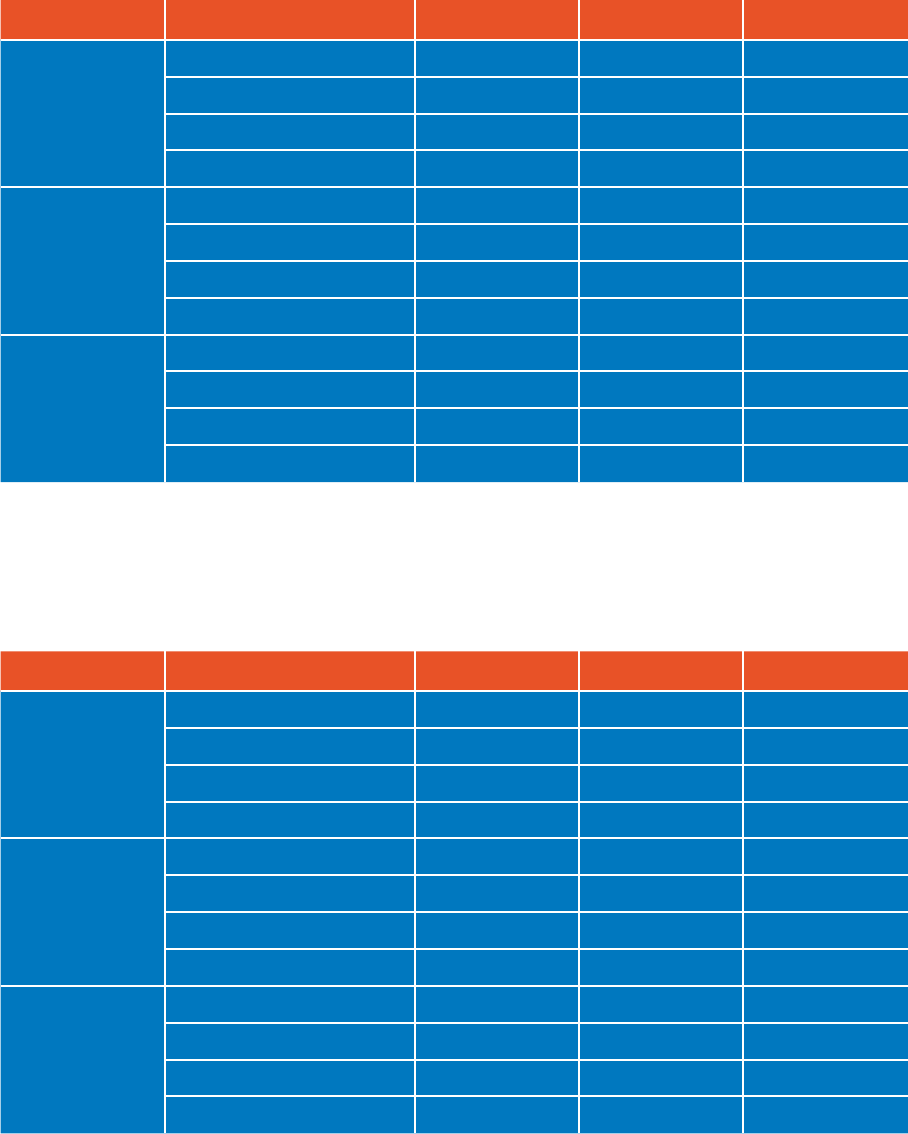

The impact of the film and high-end television tax

reliefs UK-wide, 2017-2019

15

* Metro London combines Greater London with Hertfordshire (from the East of

England) and Buckinghamshire and Surrey (the South East of England) to form

a Metro London region that better reflects the geography of film and HETV

production, given that several of the major studio facilities are located in these

counties. Beyond these changes, the study continues to use the NUTS 1

regions including the South East, which exludes Buckinghamshire and Surrey

Note: Production spend is the direct expenditure on making films and high-end

television productions in each nation. GVA and FTE figures include broader value

and employment generated by production spend through the HETV and film

content value chains (including direct indirect and induced impacts)

The impact of film and high-end television

tax reliefs UK-wide, 2017-2019

Metro London*

Scotland

Northern Ireland

Wales

England's regions

excluding Metro London

Employment (FTEs)

106,528

HETV

GVA

£6.11bn

Employment (FTEs)

155,487

Film

GVA

£11.42 bn

Production

spend

Production

spend

£3.14bn

£5.12 bn

Employment (FTEs)

42,899

Film

GVA

£2.70bn

Production

spend

£922.0m

Employment (FTEs)

3,990

HETV

GVA

£209.2m

Production

spend

£268.3m

Employment (FTEs)

5,645

HETV

GVA

£28 6.1m

Production

spend

£266.5m

Employment (FTEs)

7,591

Film

GVA

£433.1m

Production

spend

£20 6 .1m

Employment (FTEs)

2,792

Film

GVA

£171.6m

Production

spend

£33.6m

Employment (FTEs)

1,621

Film

GVA

£84.7m

Production

spend

£16.0m

Employment (FTEs)

3,733

HETV

GVA

£214.7m

Production

spend

£126.9m

Employment (FTEs)

28,394

HETV

GVA

£1.53bn

Production

spend

£895.1m

16

CONTEXT

1

17

Screen Business provides a comprehensive analysis of the economic contribution of the UK’s

screen sector tax reliefs: Film Tax Relief (FTR), High-end Television Tax Relief (HETR), Animation

Tax Relief (ATR), Children’s Television Tax Relief (CTR) and Video Games Tax Relief (VGTR).

These reliefs help to make the UK a competitive and stable market to develop and produce

content. While the reliefs are a primary driver of production and development growth in the

UK screen sectors, the UK’s highly developed production and development offer are also key

success factors. There is a world-renowned base of talent and creative businesses in the UK,

as well as a specialised offer of physical infrastructure, skilled crew and supply-chain businesses,

which has developed over many years. These areas continue to see strong investment and

strategic development.

Screen Business is published against a backdrop of an unprecedented explosion of screen

production – driven by voracious global consumption and major investment flows from

established players and newer market entrants. In 2019, global expenditure on feature film and

television production – ie investment in scripted film and television and documentaries, but not

sport, news or commercials – was estimated to have reached $177 billion.

1,2

As a result, the

screen sector is a powerful economic driver – particularly in jurisdictions, such as the UK, which

have a highly-developed development and production offer and a stable incentives base.

Undertaken by Olsberg•SPI with Nordicity, and commissioned by the British Film Institute (BFI)

through its National Lottery-supported Research and Statistics Fund, Screen Business updates

previous analyses published in 2015 and 2018.

This edition of the study extends the focus of previous versions of Screen Business by examining

a broader three-year timeframe, spanning 2017, 2018 and 2019.

The analysis is consistent with the 2018 version of Screen Business and applies HM Treasury

Green Book principles and best practice economic modelling to accurately estimate the

impact of these important revenue-generating tax reliefs for the economy, HM Government,

infrastructure investment and employment.

3

A number of new and expanded elements are also included. For the first time, an analysis of the

impact of FTR and high-end television (HETV) production is provided for the UK’s nations and

England’s regions as well as a detailed assessment of key global incentive models that compete

with the UK. As with the 2018 edition of Screen Business, the impact of the tax reliefs on the

visual effects (VFX) sector has also been analysed. While not a direct recipient of its own tax relief,

UK post-production including VFX does qualify within the reliefs, and the sector is an important

and creative element of the UK production value chain.

The study period ends before the onset of the global COVID-19 pandemic, and its impacts

have not been analysed. Nevertheless, this edition of Screen Business will provide an important

benchmark by which impacts can be measured in the future.

1. Global Screen Production - The Impact of Film and Television Production on Economic Recovery from COVID-19. Olsberg•SPI, 25

June 2020. Accessible at: https://www.o-spi.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Global-Screen-Production-and-COVID-19-Economic-

Recovery-Final-2020-06-25.pdf

2. According to data from Newzoo, the global video games market generated revenues of $144.4 billion in 2019, though this revenue

metric is not directly comparable with film and television production expenditure. Global Games Market to Generate $175.8 Billion in 2021;

Despite a Slight Decline, the Market Is on Track to Surpass $200 Billion in 2023. Newzoo, 6 May 2021. Accessible at: https://newzoo.

com/insights/articles/global-games-market-to-generate-175-8-billion-in-2021-despite-a-slight-decline-the-market-is-on-track-to-surpass-

200-billion-in-2023/

3. One exception in terms of continuity is VGTR. While the approach is consistent with that used in the 2018 edition of Screen Business

across FTR, HETR, ATR and CTR, it has been necessary to undertake a revised approach for VGTR because a significant reporting lag

means that it can take several years for actual expenditure figures to consolidate. An estimation of spend for VGTR was therefore

undertaken

2

KEY FINDINGS

18

19

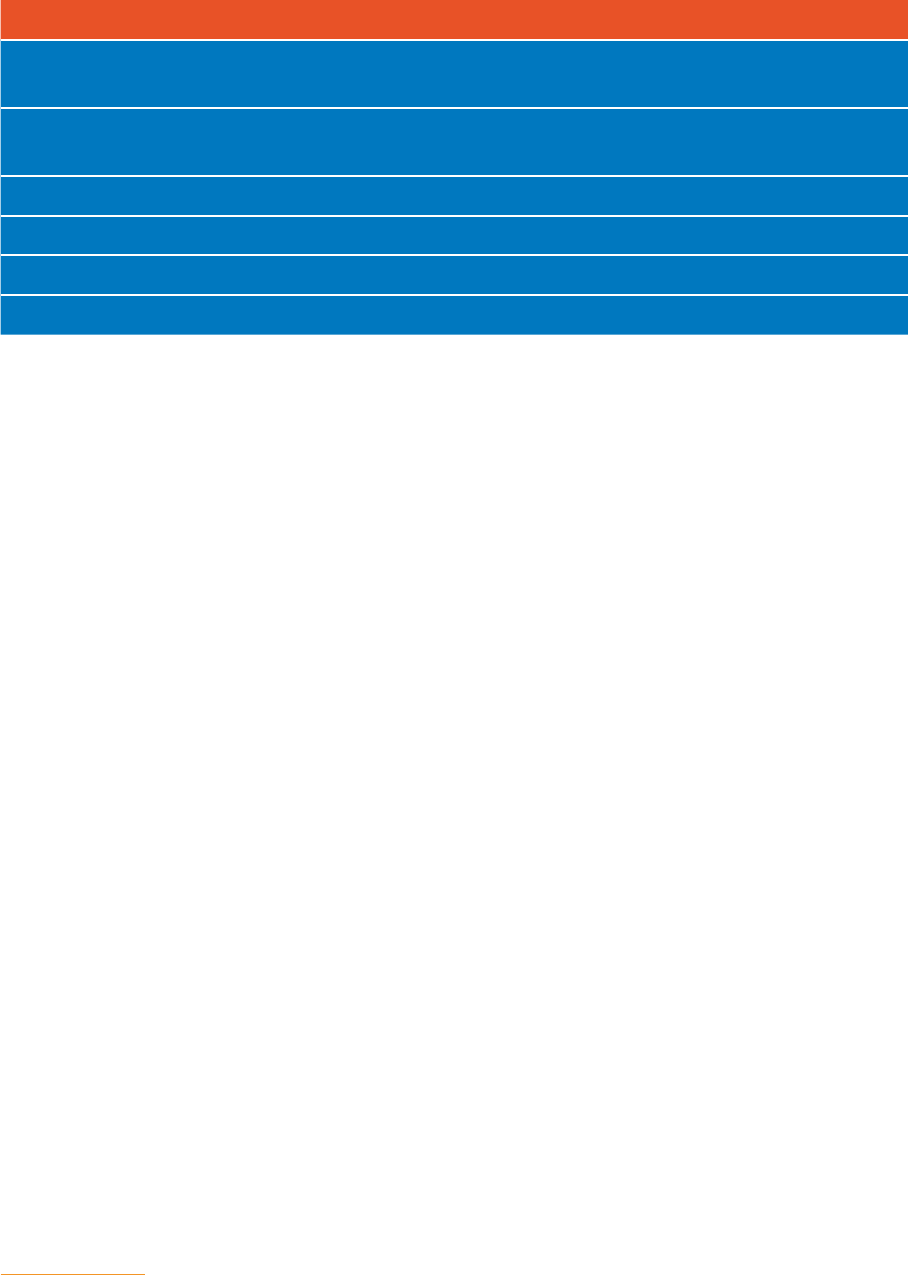

Analysis of the economic contribution of the UK’s screen sector tax reliefs focuses on the

following key areas:

• Investment in film and television production and video games development

4

• Inward investment

• Employment

• The UK economy

• Productivity

• Other benefits such as merchandising, tourism and UK brand promotion

• Return on investment (RoI)

• The impact of film and high-end television (HETV) in the UK nations and England’s regions

• The ripple effect of film and HETV spend into other business sectors

• UK film and television studios

• Innovation

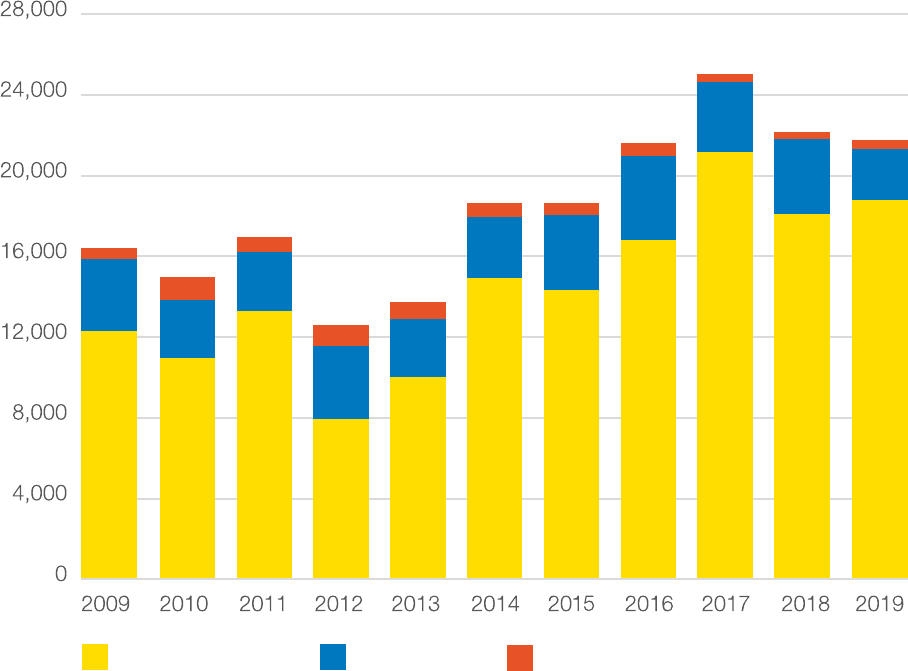

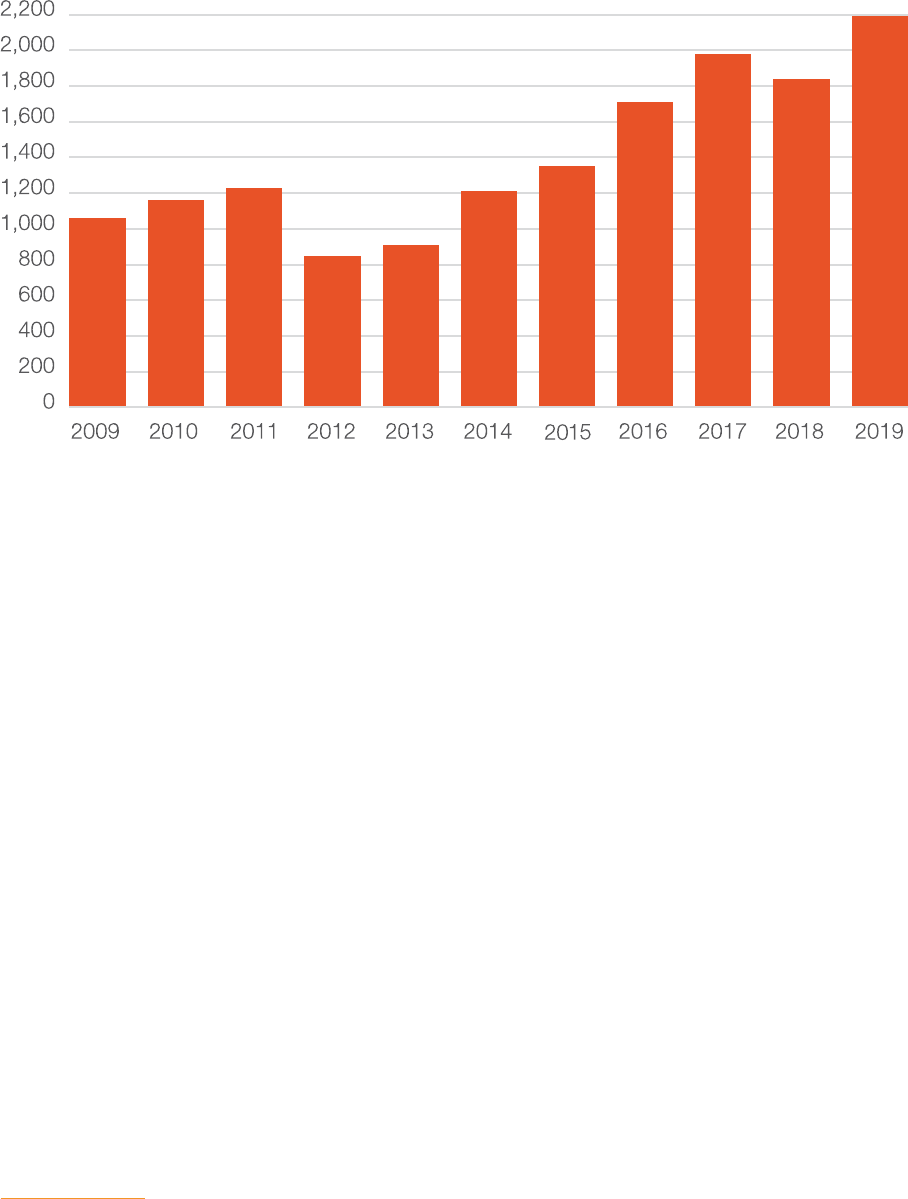

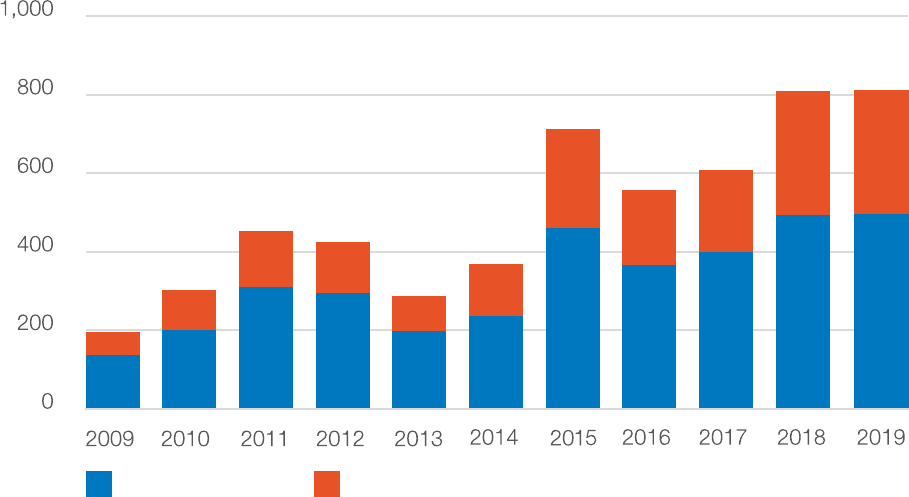

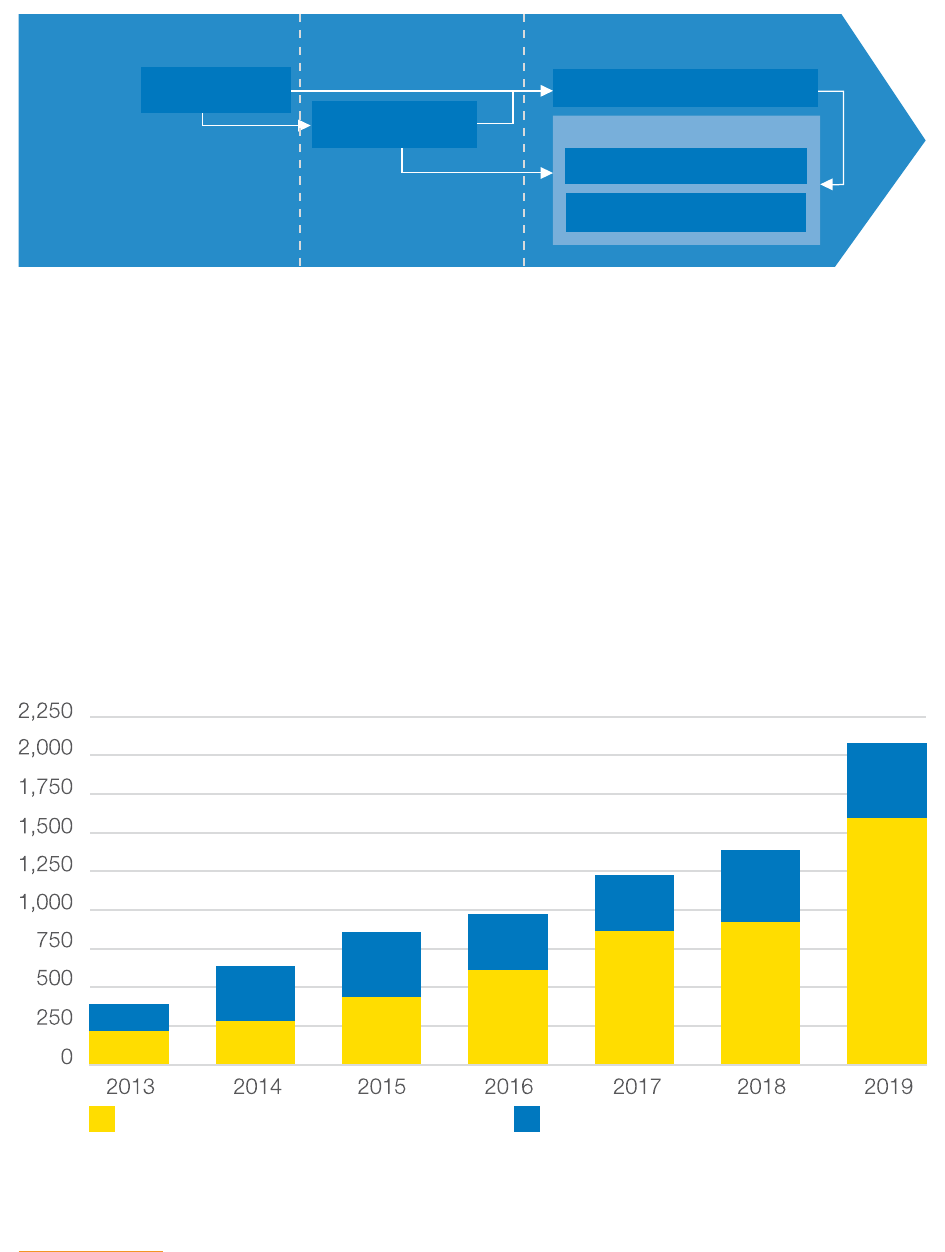

2.1. Delivering growth in production and

development investment

• Production and video games development supported by the UK screen sector tax reliefs –

ie Film Tax Relief (FTR), High-end Television Tax Relief (HETR), Animation Tax Relief (ATR),

Children’s Television Tax Relief (CTR) and Video Games Tax Relief (VGTR) – reached a record

total of £5.11 billion in 2019, an 18.4% increase on 2017. FTR production represented 39.5%

of this total in 2019, while HETR production contributed 40.7% in 2019. VGTR contributed

16.9%, while ATR and CTR contributed 1.3% and 1.7% respectively.

5

• While the tax reliefs have driven growth in the screen sectors, the UK’s base of talent,

skills, physical infrastructure and supply-chain businesses also contributes to its global

competitiveness.

• UK production spend on film was above £2 billion in each of the years analysed for this study.

In 2019, spend was £2.02 billion, which represents an increase from £849.2 million in 2007 –

the year that FTR was introduced.

6, 7

• High-end television (HETV) production supported by the tax reliefs increased from

£1.23 billion in 2017 to £2.08 billion in 2019.

8

This represents an increase from £392.8 million

in 2013 – the year that HETR was introduced.

9

4. While development is a process across the screen sectors, it is used in this study to refer to the development of video games

5. Due to reporting lag, production and development totals are expected to be revised upwards in the coming years

6. Film, high-end television and animation programmes production in the UK: full-year 2020. The BFI Research and Statistics Unit (RSU),

4 February 2021. Accessible at: https://core-cms.bfi.org.uk/media/6334/download

7. 2007 total sourced from the BFI RSU

8. Film, high-end television and animation programmes production in the UK: full-year 2020. Ibid

9. 2013 total sourced from the BFI RSU

20

• Video games development spending supported by VGTR was an estimated £700.8 million in

2017, £791.0 million in 2018 and £860.4 million in 2019.

10

• The value of animation programme production supported by the tax reliefs declined to

£65.3 million in 2019, from £84.5 million in 2018. This represents a decline from £79.9 million

in 2013 – the year that ATR was introduced.

11

• Children’s television production spend was £74.1 million in 2017, £117.4 million in 2018 and

£86.0 million in 2019. This represents an increase from £43.4 million in 2015 – the year that

CTR was introduced.

12

• While the UK is an attractive production and development market for domestic and

international investors – with an established base of skills, infrastructure and creative talent

– the tax reliefs are a cornerstone element of the UK’s ability to compete for and grow

production and development.

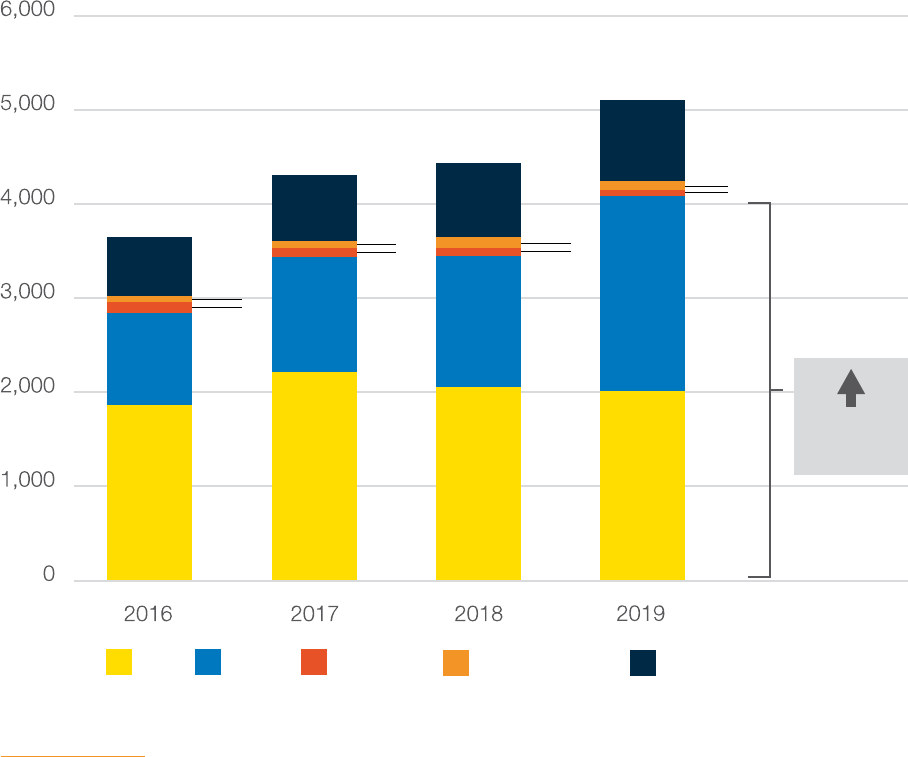

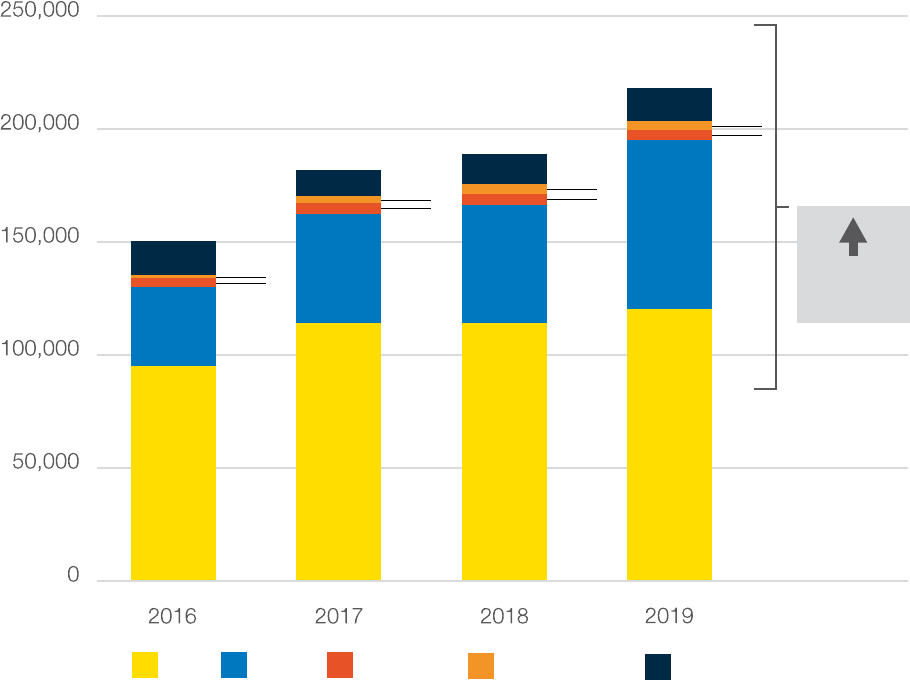

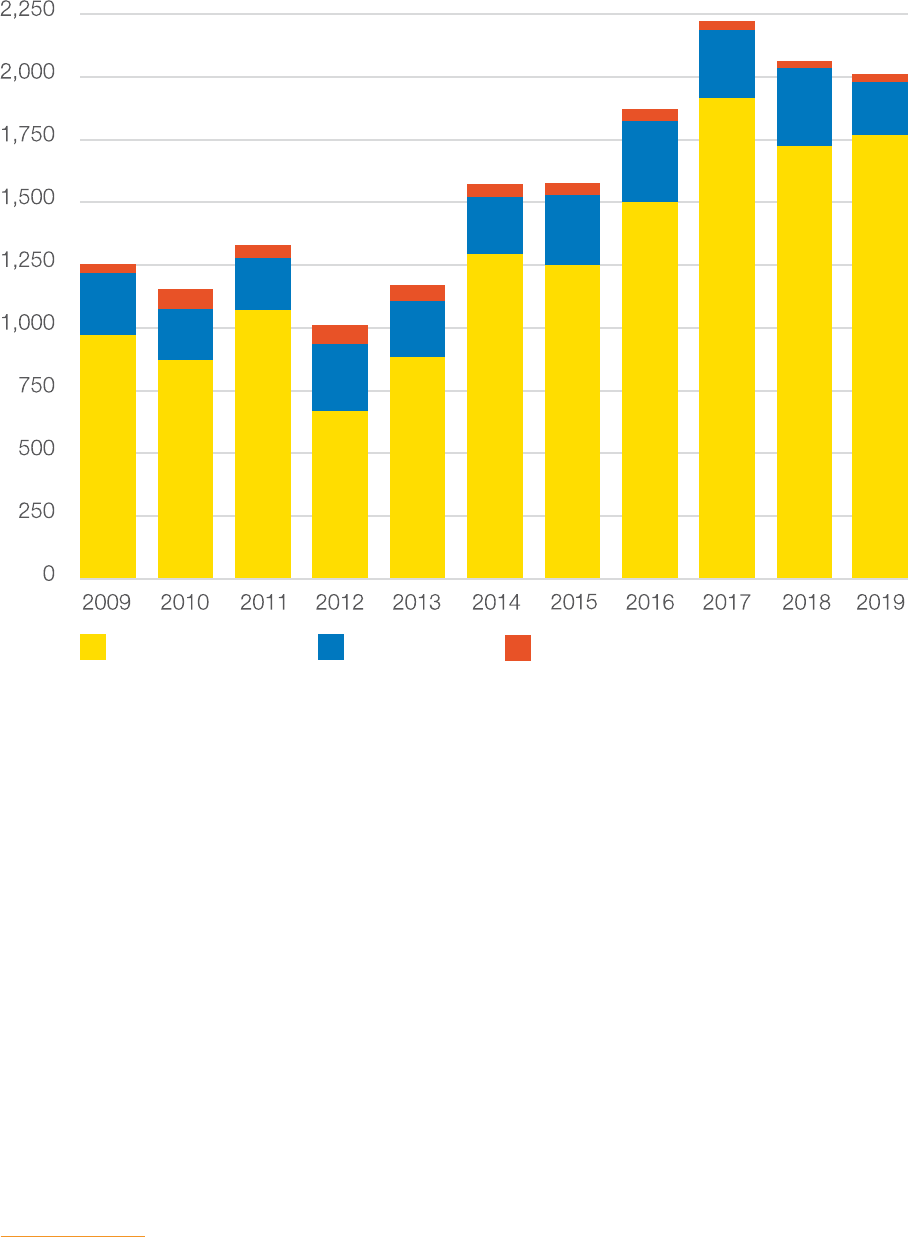

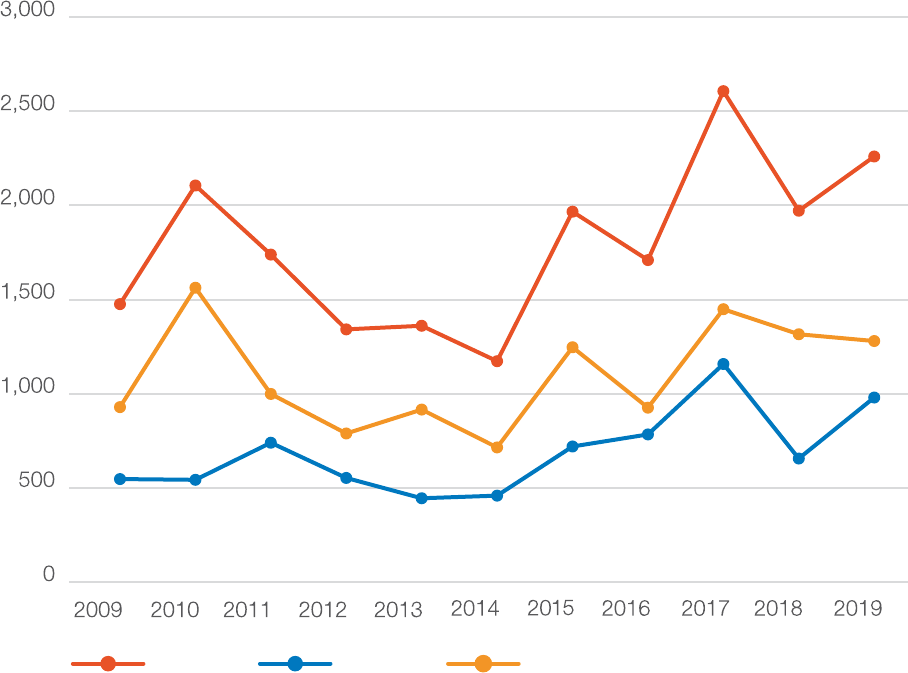

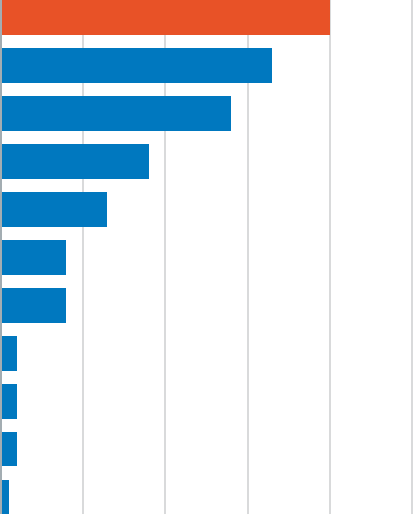

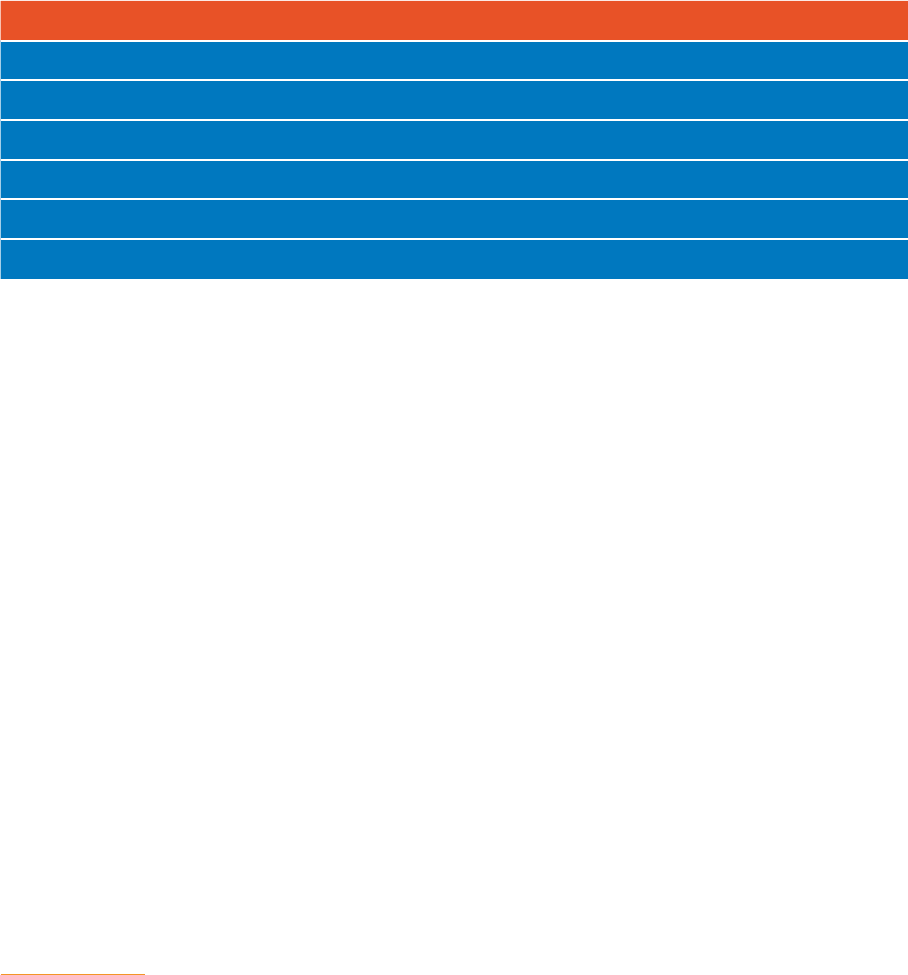

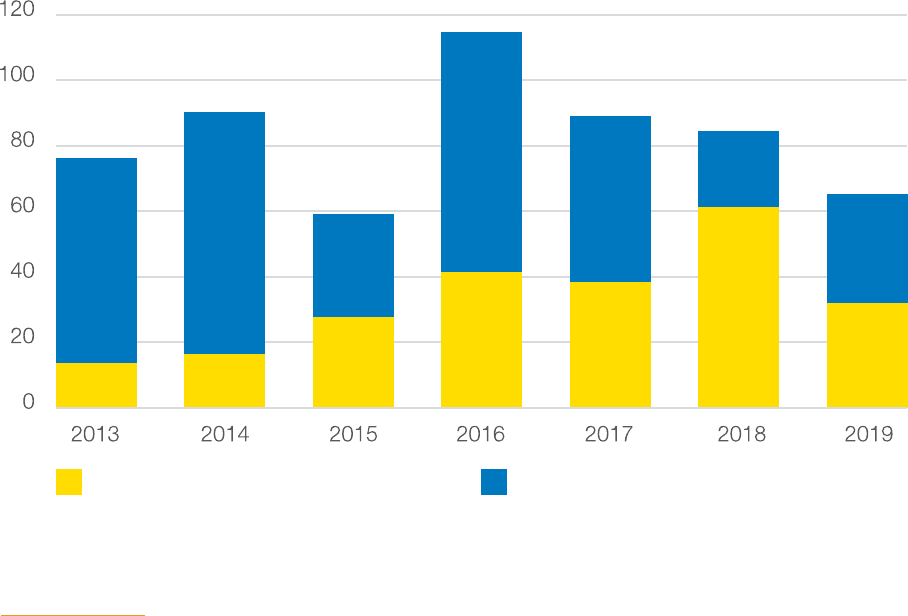

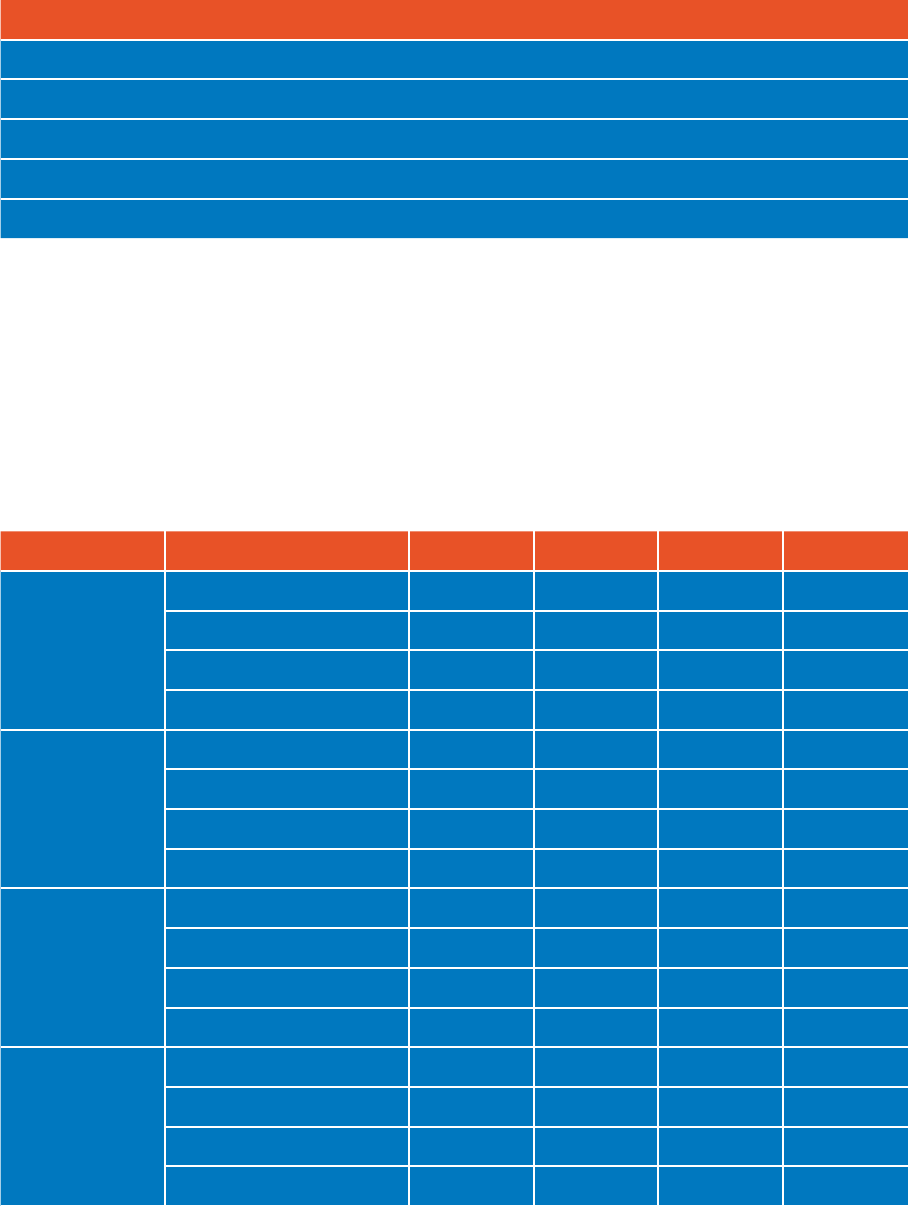

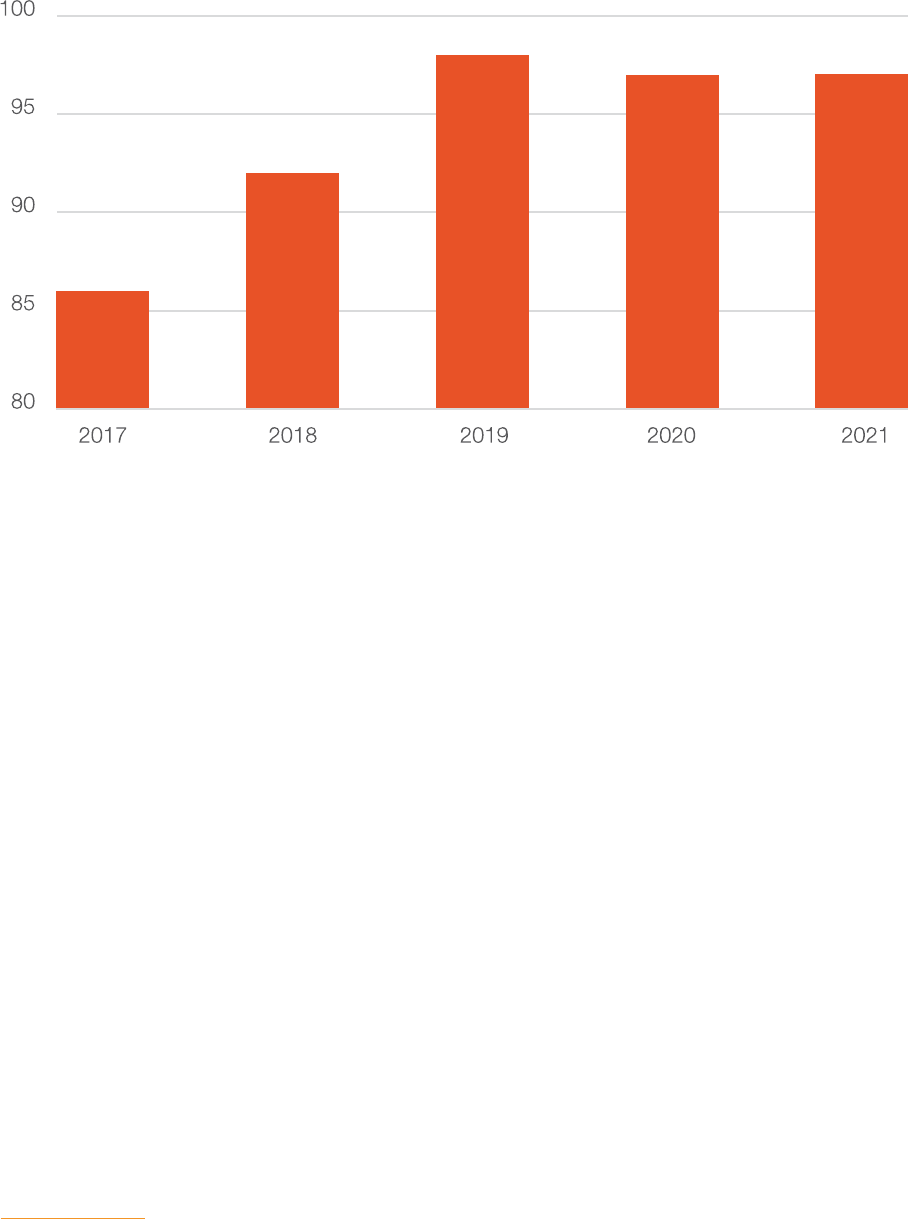

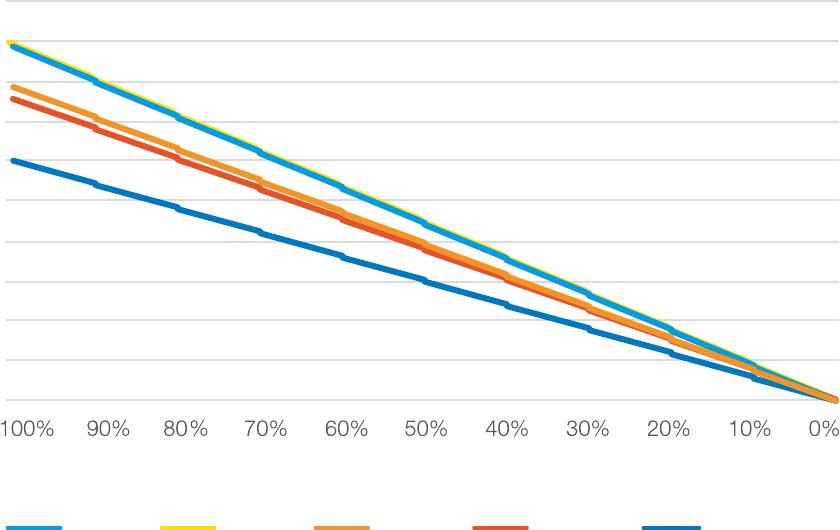

Figure 1

Growth in UK spend supported by the screen sector tax reliefs, 2016-2019 (£m)

10. Because of a significant reporting lag, a different approach to estimating expenditure has been undertaken for VGTR. As the 2019

total is an estimation, it has not been compared to spend in the year that VGTR was introduced, unlike the other sectors in this section

11. 2013 total sourced from the BFI RSU

12. 2015 total sourced from the BFI RSU

1,871.9

977.2

624.5

65.8

114.7

74.1

89.0

117.4

84.5

86.0

65.3

700.8

791.0

860.4

1,226.1

1,390.6

2,078.3

2,220.9

2,061.3

2,015.8

5,105.8

4,444.8

4,310.9

3,654.1

Film HETV Animation

Video GamesChildren's TV

+18.4%

Spend

Growth

2017-2019

Production/development

spend £m

Source: The BFI

21

2.2. Driving inward investment

• On a combined basis, the screen sectors in receipt of tax relief attracted significant amounts

of inward investment into the UK between 2017 and 2019.

13

• Throughout this period, spend on inward investment production accounted for the vast

majority of film production in the UK. In 2019, inward investment film production reached

£1.77 billion, or 87.9% of total film spend. With co-productions, this increases to 89.7% of

total spend.

• Of the £2.08 billion spend on qualifying HETV production in the UK in 2019, £482.4 million

was contributed by domestic UK productions and just under £1.60 billion – 76.8% of the total

– by inward investment and co-production spend.

• Of the £65.3 million spent on the production of animation programmes supported by tax relief

in 2019, £31.8 million – 48.7% of the total – was contributed by inward investment and co-

production spend.

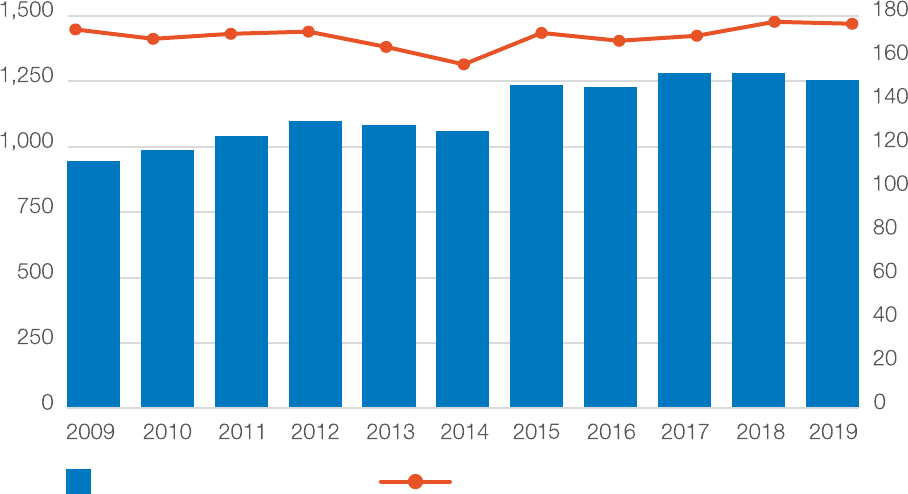

2.3. Growth in employment

• Screen sector production and development is a strong generator of employment.

• In 2019, the screen sector value chain generated 156,030 full-time equivalent (FTE) jobs

(ie from direct, indirect and induced impacts) in comparison to 132,300 in 2017.

• Growth in HETR-related employment has been significant since 2017. A total of 64,310 FTEs

were generated in the sector’s value chain (ie including direct, indirect and induced impacts)

in 2019. This represents an increase of 57.8% from 40,760 FTEs in 2017.

• FTR-related employment in the sector’s value chain decreased from 73,000 in 2017 to

68,930 in 2019 which relates to fluctuations in total production expenditure across the

study timeframe.

• Employment in the VGTR-related value chain grew by 31.3% between 2017 and 2019, from

11,450 in 2017 to 15,030 in 2019.

• ATR-related employment in the sector’s value chain was 3,730 FTEs in 2019. This

represented a decline of 9.3% from 2017.

• CTR-related employment increased by 35.2% between 2017 and 2019, from 2,980 FTEs

to 4,030.

• Screen sector production and development supported by the tax reliefs in 2019 – ie overall

economic contribution including direct, indirect, induced and spillover impacts – generated a

total of 218,790 FTEs, an increase of 20.3% on 2017.

14

13. The BFI’s definition of an inward investment production is a feature film, HETV programme or animation programme which is substan-

tially financed and controlled from outside the UK, where the production is attracted to the UK because of script requirements, the UK’s in-

frastructure or UK tax reliefs. Many (but not all) inward productions are UK films, HETV programmes or animation programmes by virtue of

their UK cultural content and the fact that they pass the cultural test administered by the BFI Certification Unit on behalf of the Secretary of

State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport. Film, high-end television and animation programmes production in the UK: full-year 2020. Ibid

14. Indirect and induced impacts include employment, employment compensation in the supply chain, and re-spending of employment

income. Spillover impacts include screen tourism, merchandise sales, UK brand promotion and esports in the video games sector

22

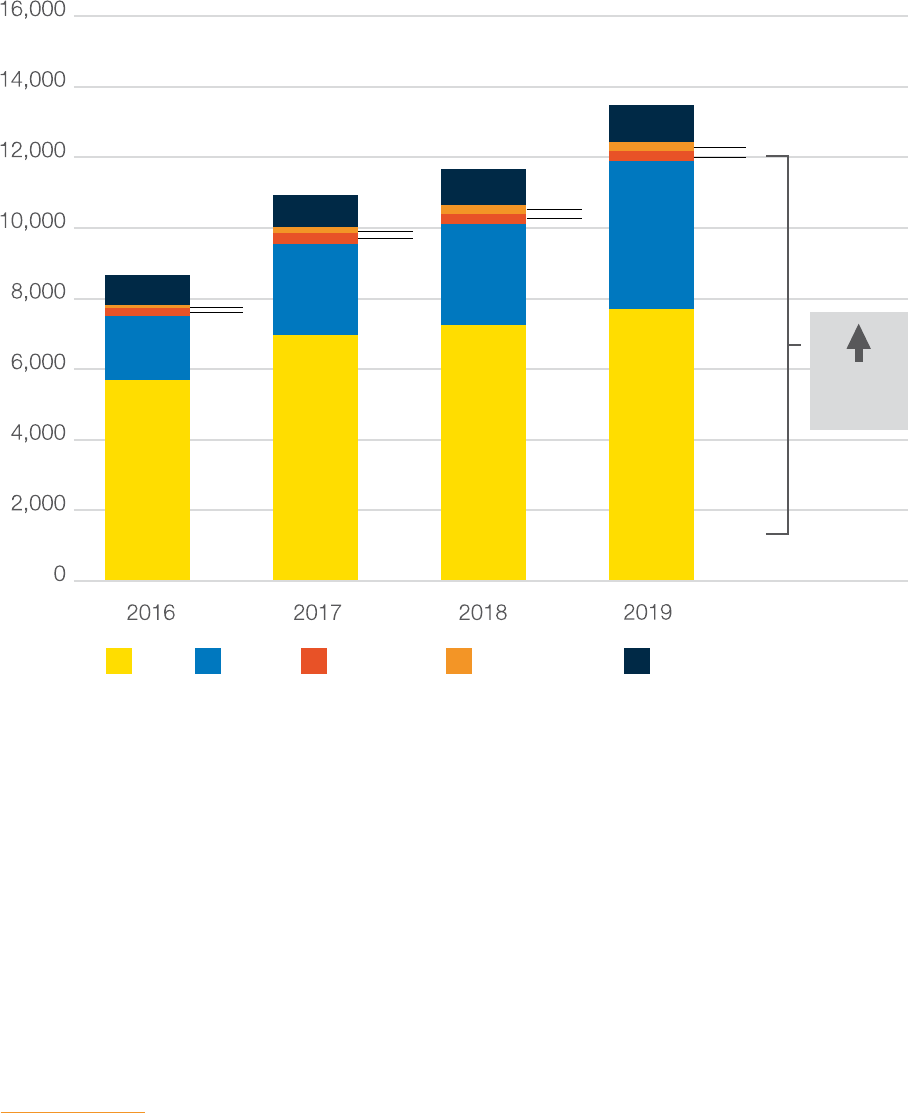

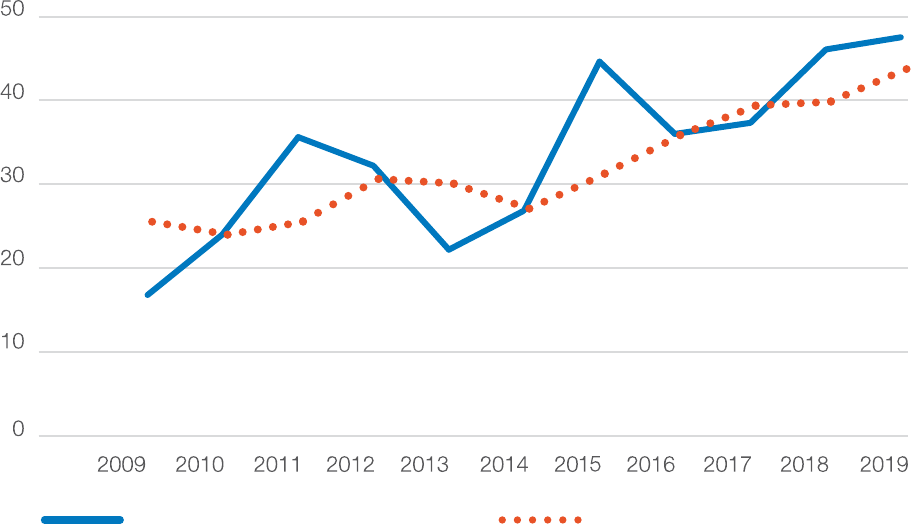

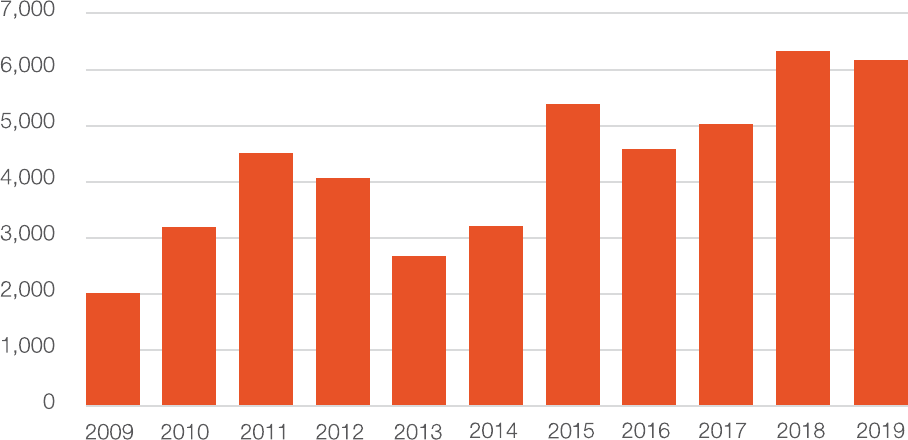

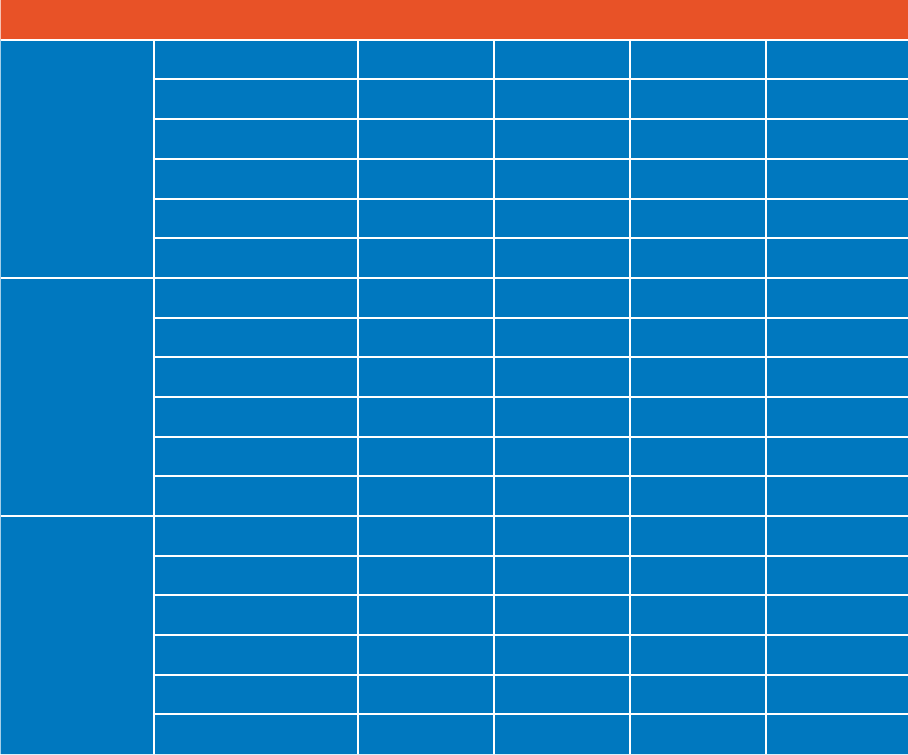

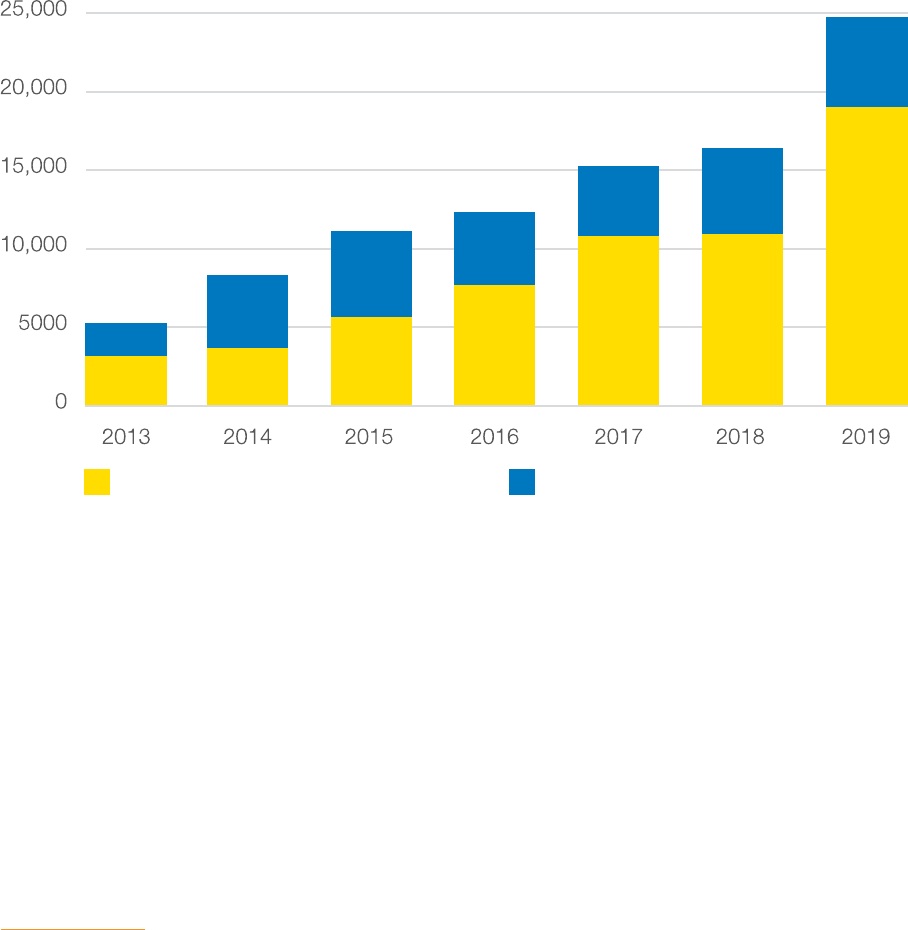

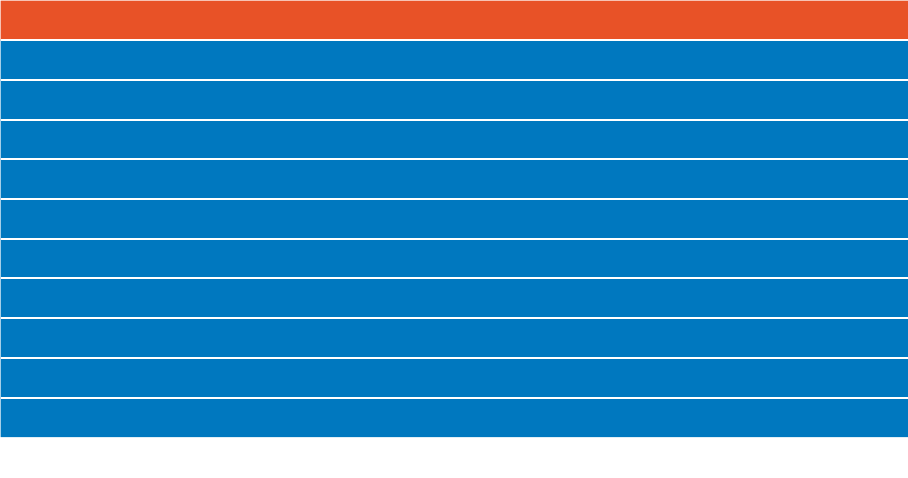

Figure 2

Growth in overall UK employment supported by the screen sector tax reliefs,

2016-2019 (FTEs, overall economic contribution including direct, indirect, induced and

spillover impacts)

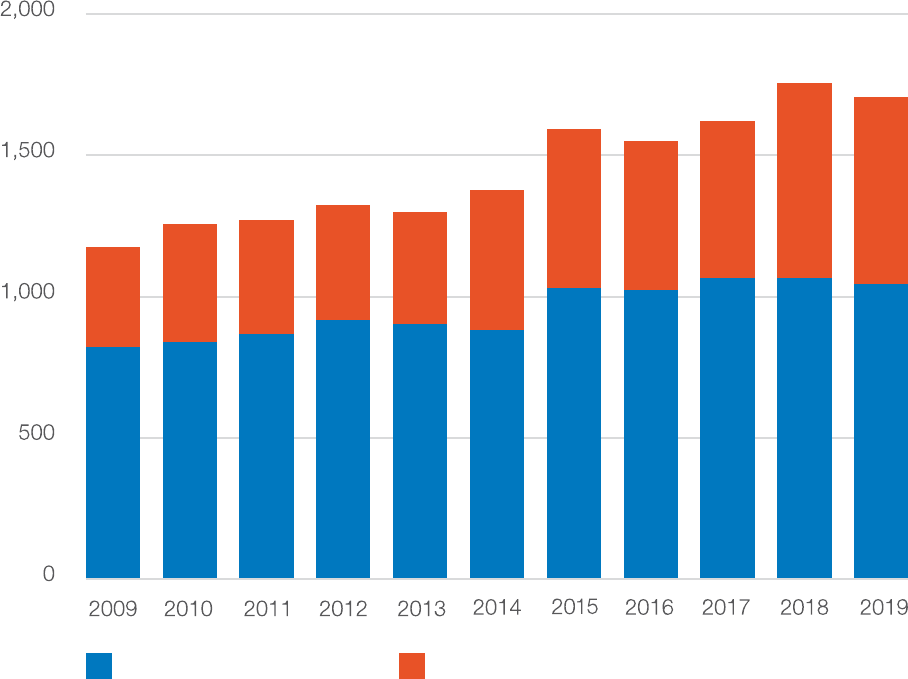

2.4. Expanding the economy

• In 2019, the tax relief-supported screen sectors together delivered a total of £13.48 billion in

gross value added (GVA) for the UK economy, including direct, indirect, induced and

spillover impacts.

• This represents an increase in overall economic contribution from £10.90 billion in GVA in

2017 and £11.70 billion in 2018.

• Together, production spend and related job creation led to the generation of significant tax

revenues for HM Government, estimated for all tax relief screen sectors in overall terms to be

£3.60 billion in 2019. This represents an increase from £3.11 billion in 2018 and £2.84 billion

in 2017.

Film HETV Animation

Video Games

Children's TV

Total FTE Jobs

34,900

14,830

95,130

114,200

48,320

52,320

114,290

120,650

74,620

11,540

14,230

15,130

4,030

4,360

4,220

4,780

2,980

4,810

1,660

4,030

218,790

189,840

181,850

150,550

+20.3%

Employment

Growth

2017-2019

23

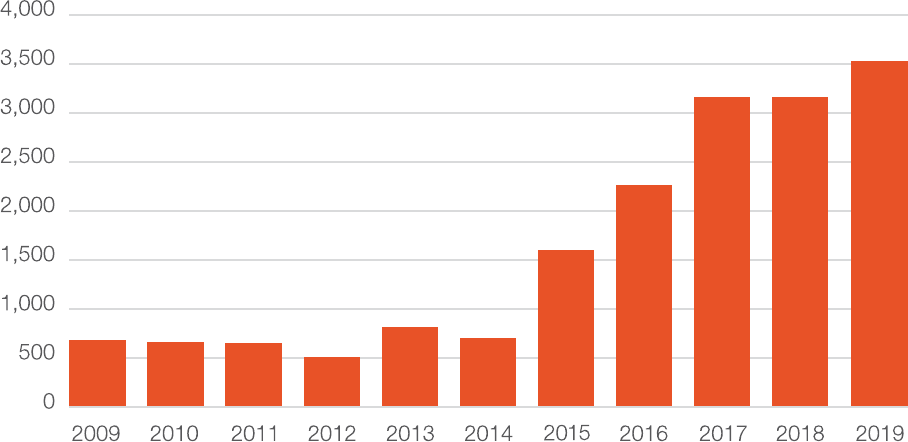

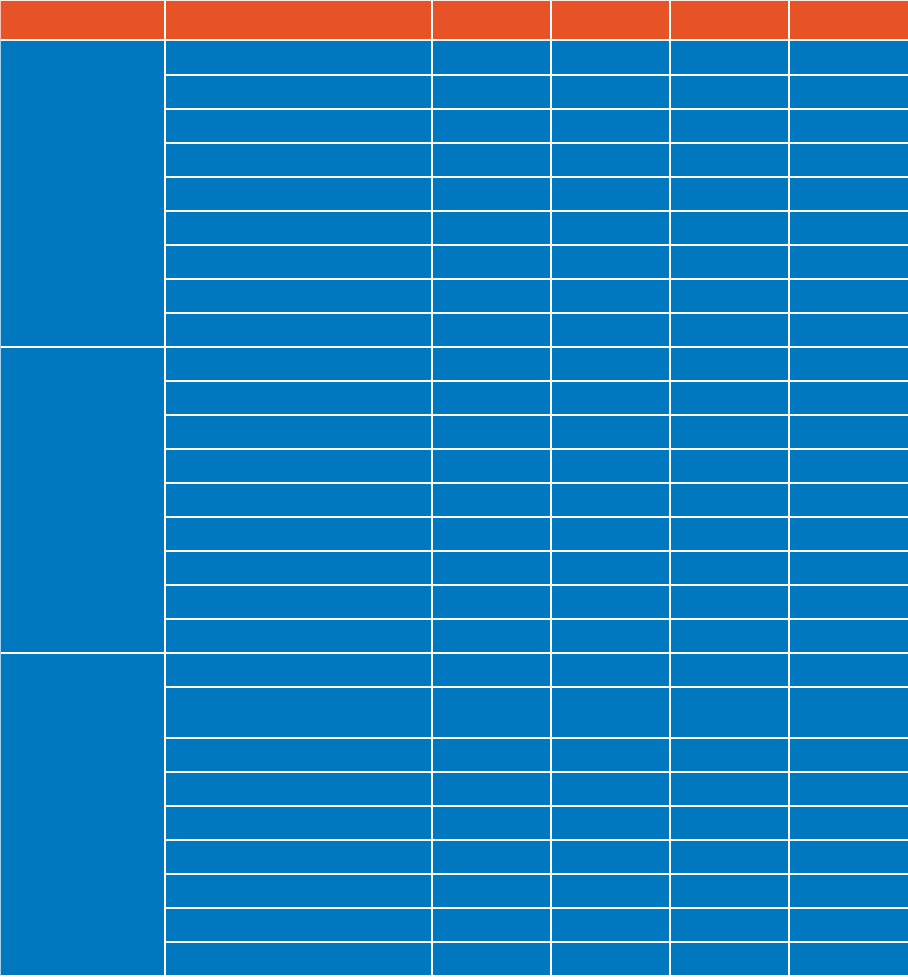

Figure 3

Growth in overall GVA supported by the screen sector tax reliefs, 2016-2019 (£m,

overall economic contribution including direct, indirect, induced and spillover impacts)

2.5. Delivering productivity

• In terms of productivity, the GVA per FTE generated across the tax relief-supported screen

sectors is higher than for the economy as a whole.

• Video games delivered the highest average productivity in 2019, with a GVA per FTE of

£121,000.

15

• In 2019, FTR, HETR and CTR displayed a GVA per FTE of £81,500. Animation production

displayed an average GVA per FTE of £84,000.

• The visual effects (VFX) sector delivered GVA per FTE of £89,743 in 2019.

• Meanwhile across the UK economy, average GVA per FTE was an estimated £66,100 in

2019.

16

15. Productivity is an economic measure that assesses how efficient firms, industries or the overall economy is in converting economic

inputs (for example, labour, capital, materials) into economic outputs (for example, finished goods or consumer services) for sale to other

firms or consumers. Productivity is often assessed in terms of labour productivity. Within economic policy, growth in productivity or labour

productivity is a precursor to higher living standards within an economy. In Screen Business, labour productivity is measured using GVA

per FTE

16. GVA per job of £58,377 has been converted to GVA per FTE based on an observed average workweek of 33.1 hours across all

employed workers

Film HETV Animation Video GamesChildren's TV

1,822.0

2,589.6

2,860.2

843.6

893.1

1,061.8

5,673.4

6,946.1

7,231.5

4,177.0

1,070.4

7,684.9

264.1

285.2

251.2

293.0

179.1

290.5

83.9

220.1

13,481.6

11,697.6

10,898.4

8,643.0

+23.7%

GVA

Growth

2017-2019

£m

24

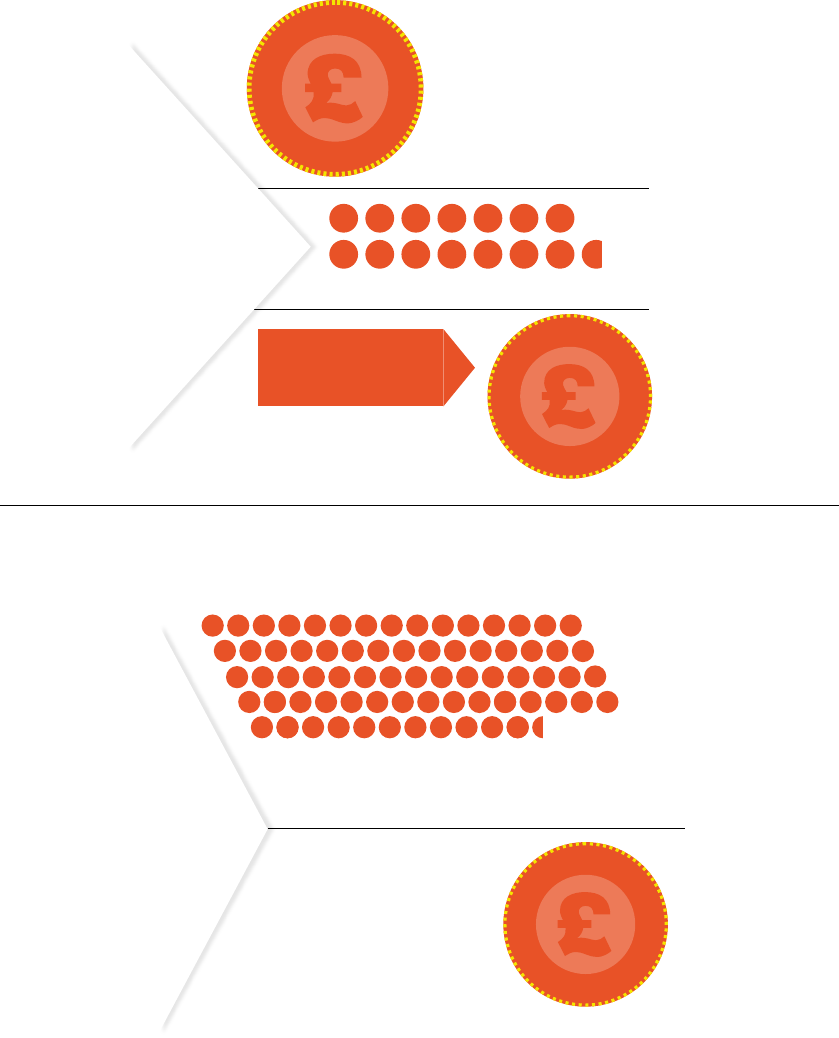

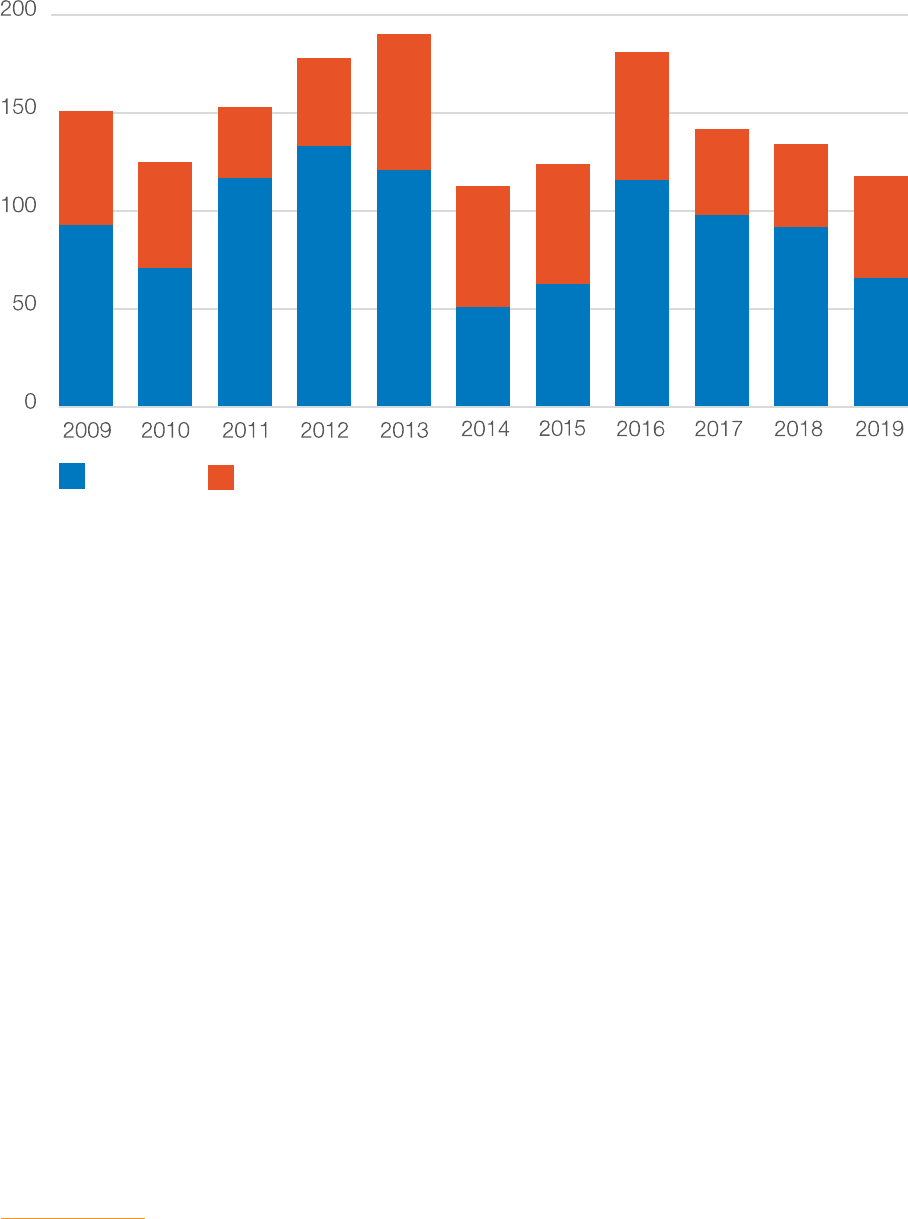

2.6. Providing return on investment

• All of the screen sectors supported by tax reliefs generated RoI when viewed in terms of the

additional GVA returned for every £1 of tax relief.

• This was most significant for FTR, which returned £8.30 in 2019 – an increase of 10.5% from

£7.51 in 2017.

• In 2019, each pound of HETR granted returned £6.44. This represented a slight decrease

from £6.67 in 2017.

17

• ATR and CTR delivered a GVA RoI of £4.53 and £3.20 in 2019 respectively.

• VGTR delivered a GVA RoI of £1.72 in 2019.

18

• The wide range in RoI is addressed in the table below.

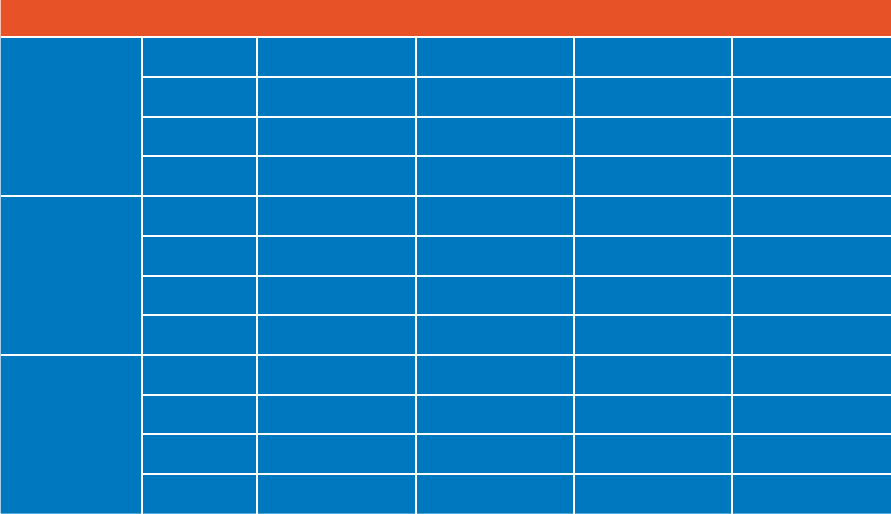

Table 1

Annual GVA return on investment, 2016-2019 (£)

Annual RoI 2016 2017 2018 2019

Film 7.47 7.51 7.96 8.30

High-end television 5.98 6.67 6.72 6.44

Animation 4.41 3.94 3.74 4.53

Children’s television 2.72 2.90 2.65 3.20

Video games 1.83 1.75 1.83 1.72

17. As explained in Section 5.8, while total expenditure increased significantly between 2018 and 2019, RoI actually reduced between

2018 and 2019. This is due to the lag between production and the economic impact of screen tourism. It results in reduced RoI because

tax relief is being paid out on increased production in the short term, while one of the sources of economic benefit – screen tourism – is

not yet appearing as a return in the economic model

18. This is not directly comparable with the VGTR RoI reported in the 2018 edition of Screen Business. See Note on RoI box

25

2.7. Supporting innovation

• In addition to generating a range of economic impacts, the UK’s screen sectors are also a

significant innovation hub.

• With technology and creativity at their core, the screen sectors are at the cutting edge of

innovation, in regard to both the products they create and the technology, processes and

skills involved in this creation.

• Notably, some creative and technical developments in one screen sector are impacting other

screen sectors – for example, virtual production technology. At the confluence of film, video

games, animation, visual effects and HETV production, virtual production allows filmmakers

to use VFX and computer graphic technologies in real time, to design sequences and provide

data and an offline (‘previs’) version of a final sequence or to combine final pixel computer

graphics (CG) with live action as it is being filmed.

• Creative and technical innovations are also benefitting the wider UK economy. StoryFutures,

for example, is a programme of research and development (R&D) projects with screen sector

businesses west of London that drives innovation in story form into storytelling, business

behaviours and audience development.

Note on RoI

All of the tax reliefs displayed positive RoI in terms of additional GVA, but a wide range of

return is evident across the sectors. This range can be linked to three key factors:

1. Sectors in which inward investment accounts for a larger share of overall spending

will display higher rates of additionality and RoI, since this inward investment spending

is more globally mobile than domestic spending on production or video games

development. Indeed, the vast majority of FTR and HETV production is inward

investment and highly mobile.

2. Inbound screen tourism is another key driver of additional GVA and a higher RoI.

Spending in the UK by inbound tourists is highly additional to the UK economy –

much like merchandise or services exports. Unlike spending on production or video

games development, tourist spending does not trigger a partially offsetting tax relief

outlay by HM Treasury. The economic benefits of inbound screen tourism are highest

in the film sector because FTR has been in place longer than the other tax reliefs and,

therefore, has helped the UK build a stock of screen tourism assets that continue

to attract inbound tourists long after the screen content has been first released. In

contrast, in the video games sector, esports has the potential to generate inbound

tourism, but not at the same scale as the screen tourism associated with films or

television programmes. The lack of screen tourism is one reason why the VGTR RoI is

lower than that for the other tax reliefs.

3. The methodology used for VGTR for this edition of Screen Business differs from the

2018 edition. As part of this, the method for measuring additionality for VGTR was

harmonised with the approach used for other tax reliefs in this study. This has led to a

lower RoI that is not directly comparable to the previous edition of Screen Business.

26

• The screen sectors create highly unique products. One example from the video games sector

is Dreams from UK developer Media Molecule. Dreams is a video game environment that not

only provides visual and immersive gameplay but, through its content creation and sharing

mechanisms, is able to develop the creativity of individuals and even offer opportunities and

routes into the video games sector.

• A range of innovation case studies are included in Section 14, outlining the scale of

development as well as the broad impacts across the UK – from leading VFX and animation

company Jellyfish Pictures establishing its first studio outside of London, in Sheffield, to the

Future Screens NI initiative and the Screen Media Innovation Lab in Northern Ireland, both

part of strategic plans to further increase local economic growth and high-value employment.

2.8. Growth in UK film and television studios

• The significant amount of expenditure undertaken in the UK by film and television projects

accessing the UK’s screen sector tax reliefs has helped to attract investment from private and

public investors into film and television production infrastructure – particularly studio facilities.

• While investment in film and television studios has, in the past, mainly centred on the Metro

London cluster, recent years have seen some infrastructure planning and development

across the UK, with investment in all UK nations and in several of England’s regions. While

comparatively limited when considered against the scale of development in Metro London,

these developments represent notable evolution of the production offer across the UK.

• Regional developments reported include new stages at Belfast Harbour Studios, the opening

of First Stage Studios in Edinburgh and new film and television studio facilities in Leeds and

Liverpool.

19, 20

• As part of this study, investment in new studio developments and in the expansion of

existing sites since 2017 has been tracked. This includes both purpose-built studios and

converted spaces.

• In total, an estimated £131.6 million was spent in building or expanding UK studios over the

period of the study between 2017 and 2019. This included £24.6 million of capital invested in

the period in building or expanding studios outside of Metro London.

• In addition to tracking capital expenditure between 2017 and 2019, analysis was also

undertaken into plans for studio projects or expansions which were announced between

2017 and 2020. This analysis focused on intended projects where planning permission had

already been granted. The timeframe was extended to the end of 2020 to reflect the fact that

the underlying investment decisions would have been based, in part, on the performance of

the UK film and television sector between 2017 and 2019.

• In total, an estimated £785.4 million of potential spend was announced for projects which

had received planning permission by the end of 2020. This is in addition to the £131.6 million

of actual spend highlighted above.

19. Belfast Harbour seeks to develop six new film and television studios. Irish Times, 17 February 2020. Accessible at: https://www.

irishtimes.com/business/economy/belfast-harbour-seeks-to-develop-six-new-film-and-television-studios-1.4175621

20. First Stage Studios to open in Leith. Film Edinburgh, 13 March 2020. Accessible at: https://www.filmedinburgh.org/News/First-Stage-

Studios-to-open-in-Leith-56570

27

2.9. The impact of the film and high-end television

tax reliefs UK-wide

• Recent years have seen increasing amounts of film and HETV production taking place outside

of the Metro London hub. This includes Game of Thrones, Line of Duty and Ordinary Love

in Northern Ireland, Outlander, Shetland and Wild Rose in Scotland and Sex Education, His

Dark Materials and Eternal Beauty in Wales. A broad range of productions have been made

in England’s regions, including Peaky Blinders, Ackley Bridge, The Personal History of David

Copperfield and How to Build a Girl.

• This study examines how total UK expenditure supported by FTR and HETR is dispersed

across the UK’s nations and England’s regions.

21, 22

• Since there is currently no standard approach to measuring UK production spend in this

way across the UK nations and England’s regions, a new production spend rate card was

developed, based on analysis of different production budgets provided by the BFI. This

analysis created a set of daily spend averages for different types of projects and budget

levels, which were then multiplied by location filming days data, sourced from national and

regional agencies.

• A significant amount of the HETV sector’s production activity impacts the UK nations and

England’s regions, with an estimated £1.56 billion in production spend, or around 33% of the

UK total, being undertaken outside of Metro London between 2017 and 2019.

• In 2019, HETV production spend generated 33,548 FTE jobs in Metro London and 15,612

throughout the rest of the UK, including direct, indirect and induced effects. Taking into

consideration the total impact of the HETV content value chain, including direct, indirect

and induced effects, 45,240 FTE jobs were created in Metro London in 2019 and 19,070

throughout the rest of the UK.

21. An analysis of the impact of the overall video games sector on the UK nations and England’s regions is provided in Section 16.1.7.

22. Since a wide range of factors influence a producer’s decision to locate a production in a nation or region – including the availability of

locations, talent, infrastructure and finance – this should be considered an analysis of how FTR and HETR spend is dispersed, and not an

analysis of how these tax reliefs specifically influence production flows around the UK

Note on Metro London

While this study uses Eurostat’s Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS) 1

approach to define England’s regions, a new Metro London definition has also been created.

Metro London combines Greater London with Hertfordshire (from the East of England) and

Buckinghamshire and Surrey (the South East of England) to form a Metro London region that

better reflects the geography of the film and television production sector, given that several

of the major studio facilities are located in these counties. The Metro London approach

overcomes the imbalance that using NUTS 1 definitions around London would have created.

Beyond these changes, the study continues to use the NUTS 1 regions including South

East, which excludes Buckinghamshire and Surrey.

28

• In GVA terms, HETV production spend generated £1.67 billion in GVA in Metro London in

2019 and £778.3 million throughout the rest of the UK, including direct, indirect and induced

effects. Taking into consideration the total impact of the HETV content value chain, including

direct, indirect and induced effects, £2.64 billion in GVA was generated in Metro London in

2019 and £1.04 billion throughout the rest of the UK.

• There is evidence of particular HETV activity between 2017 and 2019 in Northern Ireland,

Scotland and Wales, as well as the North West of England, the South West of England, and

Yorkshire and the Humber.

• The film sector, in comparison, has been more focused on Metro London – partly because

of the region’s developed and long-standing base of high-end studio facilities, supply chain

businesses and crew. Nevertheless, outside of Metro London, the analysis shows that

film production activity has been taking place in Scotland, the South East of England and

Yorkshire and the Humber, as well as other locations. Film spend generates significant

impacts across the UK, with around £1.18 billion spent outside Metro London between 2017

and 2019, representing around 19% of the total.

• In 2019, film production spend generated 37,685 FTE jobs in Metro London and 7,775

FTEs throughout the rest of the UK, including direct, indirect and induced effects. Taking

into consideration the total impact of the film content value chain, including direct, indirect

and induced effects, 49,845 FTE jobs were created in Metro London in 2019 and 19,085

throughout the rest of the UK.

• In GVA terms, film production spend generated £1.96 billion in GVA in Metro London in

2019 and £404.1 million throughout the rest of the UK, including direct, indirect and induced

effects. Taking into consideration the total impact of the film content value chain, including

direct, indirect and induced effects, £3.74 billion in GVA was generated in Metro London in

2019 and £1.24 billion throughout the rest of the UK.

2.10. The ripple effect of film and high-end

television production

• In addition to the macro-economic effects modelled by this study, research has also been

undertaken into specific micro effects generated by film and HETV productions in the UK.

• Film and HETV production are specialist manufacturing processes which require significant

inputs such as workers, equipment, infrastructure and services.

• While some of these inputs will be sourced directly from the screen sector – ie from

individuals or vendors who only work in film and HETV production – a significant degree

will be hired from other areas of the economy. This is referred to as the ripple effect – ie the

micro-economic impacts that each production generates for other business sectors.

• To demonstrate this impact, forensic analysis of three production budgets was undertaken.

For each project, production spend was assigned to the business sector into which the

money was spent. The focus of the analysis was on below-the-line production expenditure.

• The analysis found that the proportion of production costs across the three projects that was

spent in the general economy was between 40% and 60% of the total. Importantly, significant

amounts (depending on the size of the production) were spent in sectors which have been

particularly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, such as travel and transport, and hospitality

and catering.

29

• The analysis also provides important insights into the regional impacts that are created by film

and HETV production. Indeed, the three projects were all made outside of Metro London: two

were filmed predominantly in UK nations outside of England, and one was filmed in an

English region. The projects were treated confidentially, and no identifying

factors have

been included.

2.11. Delivering wider benefits

• Spillover impacts – including merchandising, inbound tourism and UK brand promotion – are

part of the overall economic contribution delivered by the tax reliefs and are also significant in

the revenues and jobs they generate.

• The UK has produced film and television drama with a strong sense of place and culture in

recent years. Projects have included The Secret Garden, which used multiple filming locations

in Yorkshire including Helmsley Walled Gardens, T2 Trainspotting, which filmed in Edinburgh,

The Favourite, which filmed at Hatfield House in Hertfordshire, and the production of Sex

Education in Wales. Meanwhile, Game of Thrones has showcased Northern Ireland’s locations

to global audiences.

• In 2017, inbound tourists spent an estimated £729.4 million in film-related screen tourism in

the UK. This is estimated to have increased to £892.6m in 2019.

• For the video games sector, the impact of esports and video games merchandise has also

been included in the overall spillovers.

23

2.12. Notes on economic impact methodology

• A bespoke economic impact model has been developed for this study, reflecting current

best practice in economic impact modelling, aligning the analysis with current government

evaluation methodology (HM Treasury Green Book).

• The previous edition of Screen Business, published by the BFI in 2018, replaced the use of

a strictly multiplier-based approach which had previously been used with an input-output

(I-O) approach. This ensures that there is temporal consistency between production spend

statistics and the economic contribution that this spend generates. It also ensures that input

data are not double counted – a risk when multipliers are applied – and also that the base

data is validated.

• The approach taken for this study is consistent with the approach used in 2018 across FTR,

HETR, ATR and CTR. For VGTR it has been necessary to undertake a revised approach.

This is because a significant reporting lag means that it can take several years for actual

expenditure figures to consolidate. To calculate impacts, the year-to-year growth in VGTR

payments reported by HM Revenue & Customs (HMRC) for 2016/17 to 2018/19 (accrual

basis) was applied to the total development spending supported by VGTR in 2016 (as

reported by the BFI) to estimate the levels of VGTR-supported development spending in

2017, 2018 and 2019.

23. As outlined in Section 6.5.2., the economic benefits of esports are counted as a spillover from the UK video games sector for the

purposes of this study on the basis that VGTR contributes to a small extent to the overall strength of the esports ecosystem in the UK.In

fact, the modelling used for this analysis found that VGTR titles only accounted for 4.4% of GVA generated by the UK’s esports industry in

2019. While esports growth is not directly driven by VGTR, some titles with esports elements have accessed VGTR

30

• For each sector, the value estimated relates only to tax relief-supported content and does not

represent all content produced, licensed, sold, viewed or exhibited in the UK.

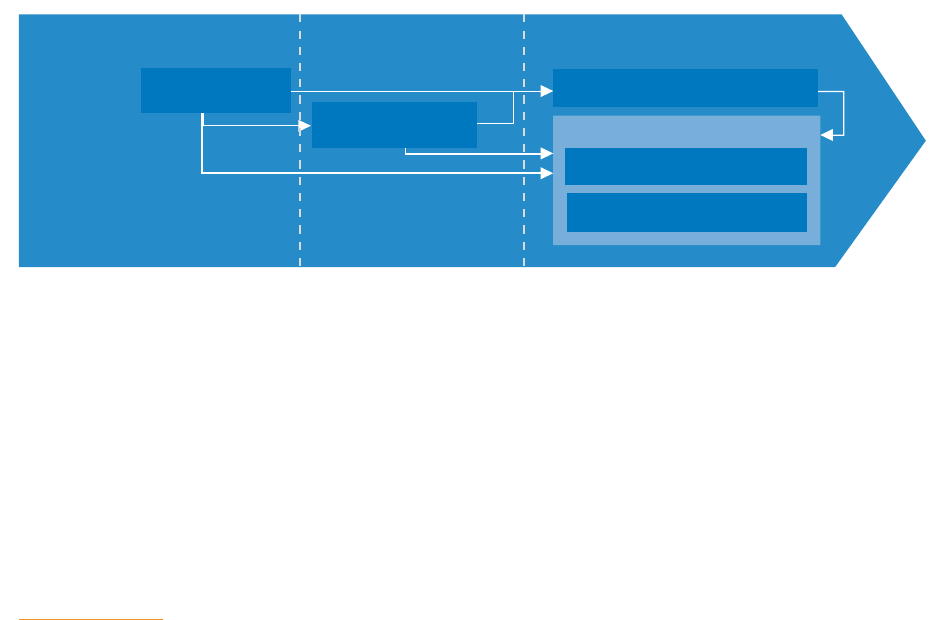

• For each sector in receipt of tax relief, economic impact is presented in several ways:

• Direct economic impact – economic activity (employment and GVA) generated directly

throughout the value chain by the element of the sector in receipt of tax relief

• Total economic impact – the direct impact throughout the value chain, plus indirect and

induced impact

24

• Overall economic contribution – the impacts of all parts of the value chain plus spillover

impacts such as merchandise and screen tourism

2.13. Key findings by sector

2.13.1. Film

• The UK has a very well-developed offer as a film production hub, combining specialist skills,

a strong talent base and established infrastructure. Films made in the UK include both

major-budget inward investment projects – such as No Time To Die and The Lion King – and

domestic UK films that achieve wide acclaim. The Favourite is an example of the latter.

• FTR has stimulated substantial growth in production expenditure in the UK film sector since

its introduction in 2007. Although there are slight fluctuations from year to year triggered

by the start of production on high-budget films, spend overall has risen from £849.2 million

in 2007 to £2.22 billion in 2017, £2.06 billion in 2018 and £2.02 billion in 2019.

25

These

fluctuations between 2017 and 2019 affect related GVA and FTEs.

• In 2017, film sector production in receipt of FTR directly contributed £1.21 billion to the UK’s

Gross Domestic Product (GDP). In 2018, the contribution was £1.13 billion and in 2019 it was

£1.10 billion.

• Films qualifying for FTR are a significant employer, directly generating 33,430 FTE jobs

throughout all parts of the value chain in 2017, 31,630 in 2018 and 31,160 in 2019.

26

In GVA

terms, films qualifying for FTR delivered £2.86 billion to the UK’s Gross Domestic Product

(GDP) in 2017 throughout all parts of the value chain, £2.88 billion in 2018 and £2.91 billion in

2019.

• With value chain, indirect and induced impacts, FTR generated 73,000 FTEs in 2017, 68,460

in 2018 and 68,930 FTEs in 2019.

• With value chain, indirect and induced spending, the total economic impact of the tax relief-

supported UK film sector in 2017 amounted to £4.93 billion in GVA in 2017, £4.91 billion in

2018 and £4.98 billion in 2019.

27

• FTR generated strong returns for HM Treasury over 2017-2019. In 2017, each pound of FTR

granted yielded an additional £7.51 in GVA for the UK economy. In 2018, this was £7.96 and

in 2019 it was £8.30.

24. See Section 3.7. for an explanation of the areas of economic impact

25. Film, high-end television and animation programmes production in the UK: full-year 2020. Ibid. As outlined, the differences in spend

across 2017-2019 may not represent decline as such, and may instead relate to the start date of high-budget films in specific years. Totals

may also increase in future in relation to the BFI’s tracking of production data. Total for 2007 sourced from the BFI RSU

26. As noted, changes over the study timeframe reflect underlying production expenditure

27. See Section 3.7. for an explanation of the areas of economic impact

31

2.13.2. High-end television

• The UK produces a range of HETV content that attracts significant attention, both within the

UK and around the world. Between 2017 and 2019, productions qualifying for HETR included

Game of Thrones, The Virtues and Quiz.

• HETV production investment has also increased throughout the UK, contributing to

production growth in the UK nations and England’s regions. This is evidenced by productions

such as Game of Thrones in Northern Ireland, His Dark Materials in Wales, Outlander in

Scotland and Peaky Blinders in England.

• Since HETR was introduced in 2013, production in the high-end television sector has

undergone a very substantial increase, with UK expenditure rising from £392.8 million in 2013

to £1.23 billion in 2017, £1.39 billion in 2018 and £2.08 billion in 2019.

28, 29

• In 2017, the HETV sector production directly contributed £707.5 million to the UK’s GDP. In

2018, the contribution was £802.4 million and in 2019 it was £1.20 billion.

• As a result, HETV production spend generated 18,600 direct FTE jobs throughout all parts of

the value chain in 2017, increasing to 19,770 in 2018 and 28,760 in 2019.

• With value chain, indirect and induced impacts, HETV generated 40,760 FTEs in total in

2017, increasing to 43,220 in 2018 and 64,310 FTEs in 2019.

• With value chain, indirect and induced impacts, HETV content generated a total economic

impact of £2.24 billion in GVA for the UK in 2017, £2.43 billion in 2018 and £3.67 billion

in 2019.

• HETR generated strong returns for HM Treasury over 2017-2019. In 2017, each pound of

HETR granted yielded an additional £6.67 in GVA for the UK economy. In 2018, GVA RoI was

£6.72 and in 2019 it was £6.44.

2.13.3. Video games

30

• The video games sector is a significant component of the UK screen landscape, with UK-

made video games – such as LEGO Star Wars – The Force Awakens, Total War: Warhammer

II, Yooka-Laylee and the Impossible Lair, Monument Valley 2 and Sackboy: A Big Adventure –

making huge commercial and cultural impacts globally.

• The UK Government introduced VGTR from April 2014. In 2017, expenditure on video games

development supported by VGTR was an estimated £700.8 million. In 2018, it was estimated

to be £791.0 million and in 2019 it was an estimated £860.4 million.

• In 2017, VGTR-supported video games development directly contributed £567.6 million to

the UK’s GDP. In 2018, the contribution was £585.3 million and in 2019 it was £559.3 million.

• Throughout all parts of the value chain, VGTR-supported spend directly generated 5,890 FTE

jobs in 2017, 6,190 in 2018 and 5,640 in 2019.

• With value chain, indirect and induced impacts, the VGTR-supported sector generated

11,450 FTEs in 2017, 14,130 in 2018 and 15,030 in 2019. In terms of GVA, the sector

generated £887.5 million in 2017, £1.06 billion in 2018 and £1.06 billion in 2019.

28. 2013 total sourced from the BFI RSU

29. Film, high-end television and animation programmes production in the UK: full-year 2020. Ibid

30. Because of a significant reporting lag in the sector, it has been necessary to revise the methodology used in the previous edition of

Screen Business for video games. See Section 2.12.

32

• VGTR-supported development generates strong returns for HM Treasury. In 2017, each

pound of VGTR granted leveraged an additional £1.75 in economic activity for the UK

economy. In 2018, it was £1.83 and in 2019 it was £1.72.

• The sector is also a driver of cutting-edge innovation. This includes innovations in technology,

which can impact widely across other screen sectors. For example, video game engine

technology is a key component of virtual film and television production, which enables

filmmakers to utilise VFX and computer graphic technologies in real time.

31

Video games also

innovate in terms of content, creating new forms of storytelling and story engagement.

32

2.13.4. Animation programmes

• The UK has a long tradition of producing animation television programmes, with content such

as The Adventures of Paddington and Pip and Posy achieving success.

• ATR was introduced in 2013 for animation programmes intended for broadcast on television

or via the internet. Animation feature films are eligible for FTR, with examples including The

Lion King, Sherlock Gnomes, Early Man and Isle of Dogs.

• Considering only ATR programme production – ie excluding other types of non-eligible

animation such as advertising – expenditure was £89.0 million in 2017, £84.5 million in 2018

and £65.3 million in 2019.

33

• In 2017, ATR programme production directly contributed £60.7 million to the UK’s GDP. In

2018, the contribution was £57.6 million and in 2019 it was £44.5 million.

• Throughout all parts of the value chain, ATR-supported spend directly generated 1,850 FTE

jobs in 2017, 1,800 in 2018 and 1,460 in 2019.

• With value chain, indirect and induced impacts, ATR-supported spend generated 4,110 FTEs

in total in 2017, decreasing to 4,100 in 2018 and 3,730 FTEs in 2019.

• With value chain, indirect and induced impacts, the total economic impact for the component

of the UK animation sector supported by tax relief amounted to £258.1 million in GVA in

2017, £261.0 million in 2018 and £254.6 million in GVA in 2019.

• ATR-supported production generates strong returns for HM Treasury. In 2017, each pound of

ATR granted leveraged an additional £3.94 in economic activity for the UK economy. In 2018,

it was £3.74 and in 2019 it was £4.53.

31. See virtual production case study in Section 14.3. While not examined in this study, video games innovations can also impact other

sectors such as transport and health

32. A case study of Media Molecule’s Dreams is included in Section 14.5.

33. It should be noted that theanimation sector’s overall sizeandvalue are considerably more significant thantheelement capturedin

relation to ATR.In 2019,theBFIcommissionedthefirst of two broader animation ‘mapping’ studies to analysethesector’s value,in-

cluding animationforcorporate and digital marketingandadvertising. Most animation companies operate mixed business models:

thesewillbeanalysedinthesecond ofthetwo mapping studies, due to be published in 2022

33

2.13.5. Children’s television programmes

• From Horrible Histories to The Athena, the UK has a long tradition of producing high-quality

children’s television programmes.

• CTR was introduced in 2015 with the aim of encouraging the production of culturally British

children’s television programmes in the UK.

34

CTR supported £74.1 million of spend in 2017,

£117.4 million in 2018 and £86.0 million in 2018.

35

• In 2017, CTR production directly contributed £43.9 million to the UK’s GDP. In 2018, the

contribution was £69.5 million and in 2019 it was £50.9 million.

• Throughout all parts of the value chain, CTR-supported spend directly generated 1,330 FTE

jobs in 2017, 1,920 in 2018 and 1,610 in 2019.

• With value chain, indirect and induced impacts, the CTR-supported sector generated 2,980

FTEs in 2017, 4,220 in 2018 and 4,030 in 2019.

• With value chain, indirect and induced impacts, the total economic contribution for the

component of the UK children's television sector supported by tax relief amounted to £179.1

million in GVA in 2017, £251.2 million in 2018 and £264.1 million in 2019.

• CTR-supported production generates strong returns for HM Treasury. In 2017, each pound of

CTR granted leveraged an additional £2.90 in economic activity for the UK economy. In 2018,

it was £2.65 and in 2019 it was £3.20.

2.13.6. Visual effects

36

• With its cutting-edge digital skills, the VFX sector is an important component of the UK screen

ecosystem. VFX is highly impactful across both film and HETV production, and UK VFX

studios such as DNEG, Milk, Framestore and BlueBolt have contributed to such innovative

and award-winning productions as Tenet, Chernobyl and His Dark Materials.

• While VFX is not the recipient of a standalone tax relief, the value of VFX as a separate

element of the production sector has been analysed due to its importance as part of the

production process. Some projects accessing tax relief may only undertake VFX work in the

UK; FTR and HETR both require at least 10% of a project’s core expenditure to be UK spend

and VFX spend alone may reach this level on some projects.

• In 2017, an estimated £301.3 million was spent on VFX services for FTR, HETR, ATR and

CTR projects in the UK. This increased to £361.9 million in 2018 and £363.5 million in 2019.

FTR-related production was the largest proportion of this over 2017-2019.

• In 2017, the direct economic impact of VFX production within the tax reliefs was

£251.9 million. In 2018, it was £302.6 million and in 2019 it was £303.9 million.

• As a result of this activity, the VFX sector generated 9,440 FTE jobs throughout all parts of the

value chain in 2017, 11,570 in 2018 and 11,840 in 2019.